On 14 March 2022, I stood along the banks of the Yuam River in Northwest Thailand and the Salween River Basin with hundreds of local residents, activists, and visitors. We met at a village, Ban Uun (a pseudonym), located beside the “two tone river”, the point where the muddy waters of the Yuam River meet the clear waters of the Ngao River around 20km from the border with Myanmar.

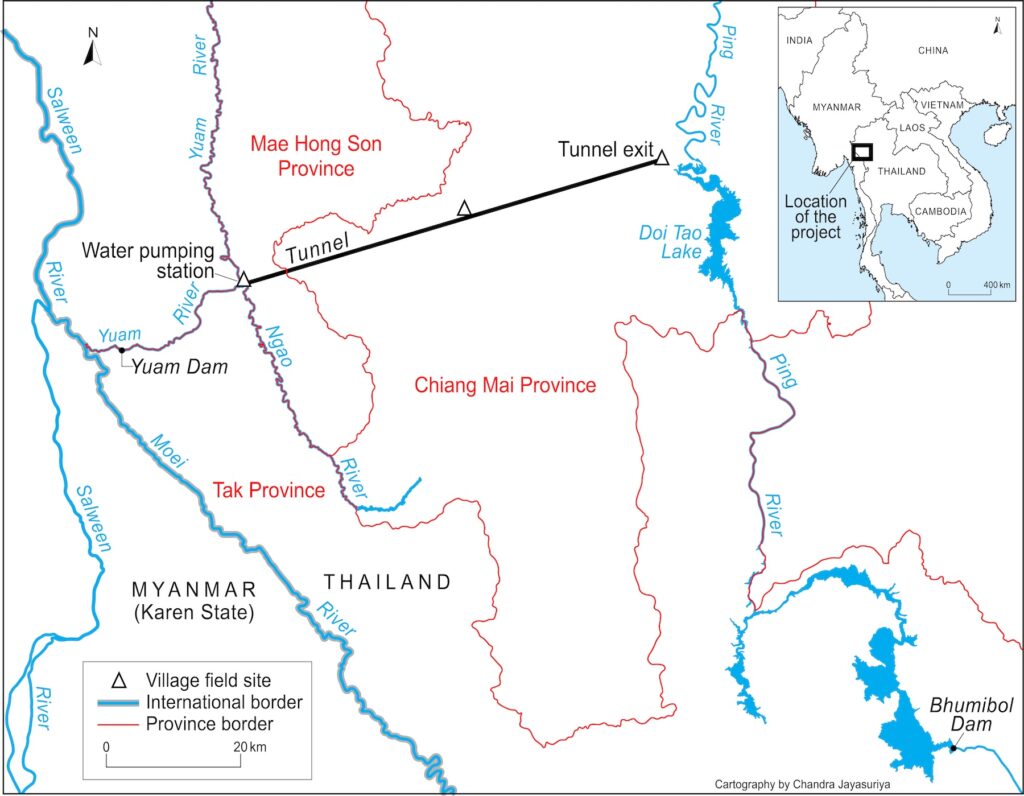

We gathered on the annual International Day of Action for Rivers (or International Rivers Day), a global day of action to protect rivers and oppose destructive developments. Activities have been held on this day in Ban Uun since a proposal to divert water from the Yuam River was revived by Thailand’s Royal Irrigation Department (RID) in 2018–19. The project would entail a 69.5m high dam on the Yuam River, creating a reservoir from which water would be diverted to Bhumibol Dam in Central Thailand, primarily for agricultural use.

The proposed Yuam River water diversion project in Northwest Thailand (Image: Cartography by Chandra Jayasuriya, University of Melbourne)

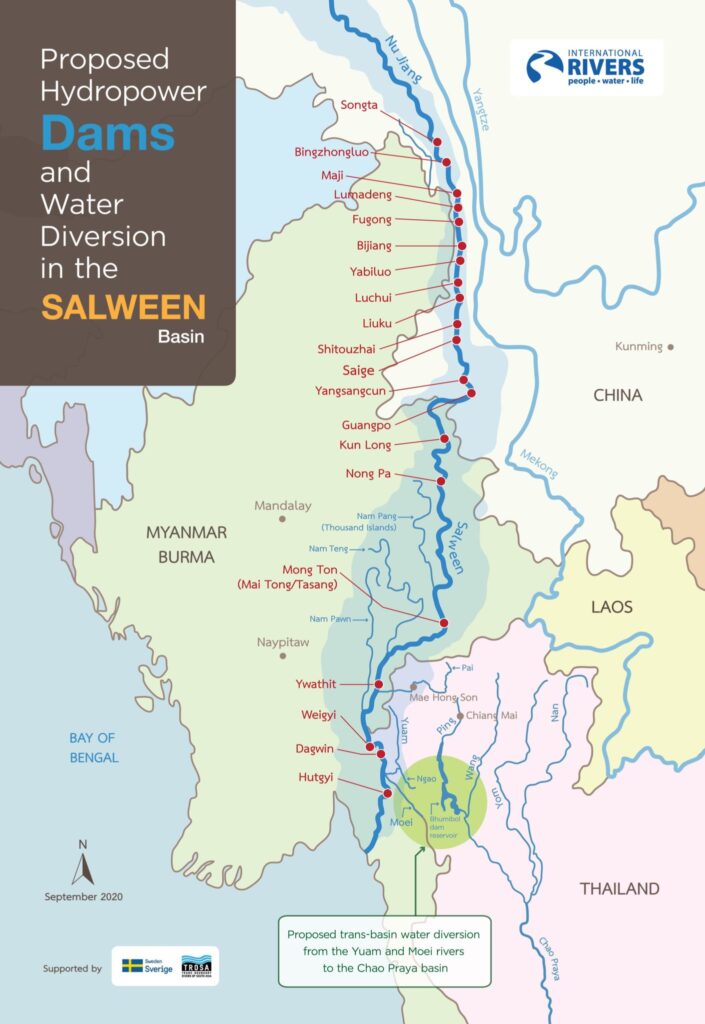

Resistance to the Yuam diversion is part of a broader movement contesting long-proposed destructive river developments across the Salween River Basin, which spans Tibet, China, Myanmar, and Thailand. The river forms the political border between Thailand and Karen State, Myanmar for 120km. Many of the Basin’s 10 million residents depend upon the river for their livelihoods and food. Residents and activists in the Basin have gathered annually on International Rivers Day for two decades to challenge proposed dams and diversions that would impact their riverine livelihoods and ecologies.

Proposed hydropower dams and water diversions in the Salween River Basin. (Image: International Rivers, 2020, Creative Commons)

The impetus to challenge such developments is sustained by the socioecological impacts of dams, including forced displacement and damage to fisheries, that are evident in nearby basins such as the Mekong. While dams and diversions have been (re)proposed, and resisted, for four decades in the Salween Basin, these projects remain unbuilt—and for now the Salween remains Southeast Asia’s longest free flowing river.

I was there among the villagers and activists in Ban Uun on International Rivers Day to understand these dynamics. Working collaboratively with key Salween civil society actors, who shaped the direction, questions, and outcomes of the research, my PhD project examined the enduring struggles of communities and civil society actors over long-proposed dams and diversions.

What emerged during fieldwork was how resistance is shaped by past legacies and present experiences of authoritarianism, conflict, and statelessness in the region. Under authoritarian rule, overtly resisting state-led development can entail risks and repercussions including threats, harassment, imprisonment or worse. In the past century, Thailand has experienced 13 “successful” and nine “unsuccessful” military coups. Military rule from a coup in May 2014 until contested elections in May 2023 was marked by shrinking political space. Myanmar returned to military rule following a February 2021 coup, which has exacerbated longstanding conflict, state violence, and human rights abuses.

Making Mainland Southeast Asia safe for autocracy

How regional elites built an “authoritarian security community”

In examining these dynamics, my work both builds upon and departs from James C. Scott’s influential conceptualisation of “everyday” resistance, defined as the “prosaic but constant struggle” by those “subject to repression”. For Scott, the “ordinary weapons of relatively powerless groups”—including foot-dragging, false compliance, arson, sabotage, and more—tend to be covert, individualistic, and spontaneous, rather than centrally organised. A lack of formal organisation and identifiable leaders can be strategic to evade state repression under authoritarian military rule, as Kevin Malseed shows in Karen State. This framing has gained widespread traction to analyse resistance under authoritarian and repressive conditions across the social sciences and in Southeast Asia.

When I started fieldwork, I expected to encounter “everyday” resistance to proposed dams and diversions. Like Scott, I found that resistance is not always overt or “visible”, with my research emphasising how resistance to development under authoritarian conditions often unfolds “under the radar”. While overt protests do occur, including on the International Rivers Day, not everyone seeks to be on the frontlines of resistance—including those lacking Thai citizenship. Moreover, many Karen residents do not speak or read Thai language fluently, and this limits their capacity to participate in legal and bureaucratic processes, such as state-led public hearings and Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) processes.

A central lesson from my research is how time is used as a resource by social movements. Departing from Scott, I found that resistance is highly organised, strategic, and enduring when taken over long periods—even if not always overtly visible. This led me to propose a conceptualisation, together with Vanessa Lamb, of “slow” resistance, defined as “actions that are strategic, incremental, and interconnected over time, but not always visible or ‘spectacular’”.

Slow resistance reflects that, under authoritarian conditions, “resistance treads a middle ground between everyday acts and broad-base movements and can generate important victories behind the scenes for … marginalised political actors,” as Miles Kenney-Lazar, Diana Suhardiman and Michael B. Dwyer find in Laos. It provides a framing to examine how resistance waxes and wanes in response to shifting political conditions. While periods of relative openness provide opportunities for more overt political action, periods of “closure” require activists and residents to work “under the radar”. I conceptualised three facets of slow resistance: duration, delay, and slow tempo, each of which I discuss in turn.

Expanding on the theme of time in resistance, my research also found that the ways in which people participate and resist is shaped by age and generation. Young people more often have Thai citizenship, higher levels of education and Thai language skills, and experience engaging with NGOs, and more often lead overt protests. Older generations engage in a range of other ways including ceremony, as I detail below.

Protests on the International Rivers Day along the Salween River in 2017. (Photo: International Rivers, Creative Commons)

Duration

A focus on duration illuminates how resistance is necessarily protracted over decades and generations in response to long-proposed dams and diversions in the Salween River Basin. While dams may temporarily be defeated, they are often (re)proposed in a different form by a shifting network of state and corporate actors, and struggles are passed down to the next generation of residents and activists.

When I asked interviewees about their struggles over the Yuam diversion, many older generation residents and activists began their stories of resistance not in the present but in the 1990s in response to the Mae Lama Luang Dam. This 100m-high dam was proposed by the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) to produce hydropower, and would have created a reservoir from which water could be diverted to Bhumibol Dam. Reflecting this, one long-term Salween activist and NGO employee, Lee, described the Mae Lama Luang and Yuam Dams as “basically the same” in terms of location, but noted that the RID “adapted” it to become a water diversion project.

While the Mae Lama Luang Dam was never built—both due to concerns over the project’s environmental impacts and a strong local anti-dam movement—affected residents see this dam as reemerging in the form of a water diversion project. This is captured by the notion of the “zombie” project that “never dies,” as long-term Thai rivers activist Pianporn Deetes contends. Similarly, Nat, a businessperson and aquatic ecology expert who is engaged in Salween actions, complained in a September 2021 interview that projects like the Yuam diversion are “like a zombie, you never kill any of these projects. You work so hard to kill them once and after 10 years they return again”. For this reason, many older generation activists who previously resisted the Mae Lama Luang Dam are again opposing the Yuam diversion.

Analysing the longue durée of development is key for understanding a range of long-proposed “zombie” dams in the region that are yet to materialise, like Thailand’s Kaeng Suea Ten Dam. This dam has been (re)proposed for more than four decades but remains unbuilt. The movement resisting this dam is seen as “successful” because it “achieved suspension” of the dam for over four decades. This highlights how delay can be used as a strategy of “slow” resistance, as I detail next. Discussing the Yuam diversion in relation to Kaeng Suea Ten Dam, Sunan, a long-term NGO employee, reflected in a May 2021 interview that “after elections … every time the politicians will propose this dam. Maybe it is different in detail, a little bit upstream or downstream. Even though they know it is very difficult, they propose it … again and again”. Reflecting this, in September 2024, the Thai government announced “plans to revive” the Kaeng Suea Ten Dam.

Delay

During fieldwork, interviewees often highlighted their efforts to delay development approvals and thereby “slow down” development. Delay can be understood as an interim goal, and outcome, of resistance in a context where it is difficult to permanently defeat “zombie” projects, including the Yuam diversion.

The EIA process is a key site of contestation over the Yuam diversion. While the EIA for the Yuam diversion was approved by Thailand’s National Environment Board in September 2021, paving the way for consideration by the Thai cabinet, residents and civil society actors argue that the EIA is “deeply flawed” and excluded them from meaningful participation in development decision-making. They also argue that the EIA includes false and misleading information including fabricated evidence of public participation and consent.

Activists and residents have focused their efforts on highlighting flaws in the EIA process to delay its approval and consideration by the cabinet. This reflects that “EIA processes have become important mechanisms for affected communities to stall, challenge, and sometimes to prevent projects,” as Eli Elinoff and Vanessa Lamb find in their review of environmental politics in Thailand over the past five decades. Activists and residents are demanding that new and improved studies be conducted to inform the EIA process and that their voices be included in decision-making.

In 2021, residents and civil society actors submitted a complaint to the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand (NHRCT) to investigate misconduct in the EIA process. This investigation is ongoing, resulting in further delays to project development. One Ajan [professor] explained in a January 2022 interview that a key strategy to delay and challenge the Yuam diversion is to “submit a petition to the NHRCT … The NHRCT can submit their own independent report. The project won’t be sent to Cabinet for consideration and will be put on hold for more information gathering”.

Delaying development is strategic as it “buys time” for activists and residents to organise more effectively. With the EIA delayed, NGOs and residents are preparing a legal case to challenge the EIA in the courts. In October 2023, 66 plaintiffs, most of whom are affected Karen residents, filed a lawsuit at the Chiang Mai Administrative Court against the five Thai state agencies who were responsible for developing and approving the EIA. The lawsuit alleges that the EIA process did not follow Thai laws mandating public participation and information disclosure, and that the EIA contains misleading information about consultation. This lawsuit is ongoing, making it difficult for state actors to proceed with development. Ban Uun residents also worked with academics from Chiang Mai University to conduct a “People’s EIA” to document local ecological knowledge and livelihoods and the project’s socioecological impacts, and thereby challenge the state-led EIA.

Slow tempos of resistance

At the fieldsites, residents engaged in actions that were slow, considered, and embodied. These actions might initially resemble Scott’s “everyday” resistance—covert acts that do not directly confront power under repressive conditions. My research demonstrates how these actions are organised, strategic, and enable and form a key part of the movement when taken over time.

I use the example of tree ordination ceremonies, or buat pa in Thai language. Led by Buddhist monks, tree ordination emerged in Thailand in the late 1980s as a strategy to protect forests from logging and development. It has since been adopted by environmental and anti-dam movements across Thailand, including to challenge the Kaeng Suea Ten Dam, and is deployed on the International Rivers Day by Ban Uun residents.

In these ceremonies, Buddhist monks and a range of participants—residents, activists, visitors—wrap orange robes around trees to ordain them. These actions themselves are slow, embodied, and deliberate. When taken collectively, these actions protect the trees, land, and water within the space demarcated by buat pa, and the human and more-than-human lives that depend upon them. These ceremonies are often led by older generation residents such as Mr. Yao, an 81-year-old resident and spiritual leader, whom I interviewed in September 2021. Mr. Yao explained the purpose of these ceremonies: “Even if we call it a ceremony … it is not just a ceremony to protect the forest or nature. The main point is to protest the dam and the Yuam water diversion project, especially by the young people, who stand up to say ‘no dam’ during this day”.

A tree ordination ceremony in Ban Uun on the International Rivers Day in 2020. (Photo: A Salween youth activist, used with permission)

Not everyone that participates in buat pa is necessarily staging a protest; these ceremonies are also a way to respect and protect nature. In Thailand, religious ceremony does not capture the attention of state authorities in the way that overt protests might. This “strategic ambiguity” enables participation by those who seek to be less visible, and for movements to persist over the long term. Slow tempos of resistance are “part of an ongoing, persistent mobilisation that does not necessarily seek to be visible or revolutionary, but serves to mobilise and bring people together” under difficult conditions. Stateless residents often participate in less overt ways, such as ceremony, collective food preparation for International Rivers Day gatherings, and voicing their concerns to community representatives in meetings.

As noted above, resistance is not only “slow”. Young people are particularly active in leading overt protests against Salween dams and diversions. Slow resistance is important because it foregrounds how diverse and often overlooked actors, including older people and stateless people, participate and resist. Slow resistance highlights how different forms, tempos, and generational strategies of resistance complement and make space for one another. Such a multipronged approach is necessary for movements to persist over time and across different political contexts. This might be overlooked by analyses focusing on more overt forms such as street protests or that draw on notions of “everyday” acts of resistance.

What is the outlook for development in the Basin and region?

What does “slow” and ongoing resistance against dams and diversions mean for projects in the Basin and mainland Southeast Asia?

Given complex hydropolitics and rising authoritarianism in the region, the answer is far from straightforward. Despite the controversies surrounding large dams, mounting evidence of their impacts, and a strong anti-dam movement, state and corporate actors continue to pursue destructive river developments, often with little accountability under authoritarian conditions.

Within Thailand, no large dams have been constructed since the controversial Pak Mun Dam, which was completed in 1994. This dam generated widespread protests including a 99-day sit-in protest on the lawn outside Bangkok’s government house and remains “perpetually contested” even during operation. Following this dam’s controversy, Thailand is pursuing dam development in neighbouring counties as both an investor and importer of electricity, which Jakkrit Sangkhamanee refers to as the “spillover” of Thailand’s “flawed hydropower decision-making processes.” For instance, EGAT is the main importer of hydropower produced in Laos by dams such as the Nam Theun 2. During recent fieldwork I conducted along the Mekong River at the Thai–Laos border in December 2025, local activists highlighted the proposed Pak Beng Dam in northern Laos as a key flashpoint; EGAT would import 95% of the electricity produced by it.

Making Mainland Southeast Asia safe for autocracy

How regional elites built an “authoritarian security community”

Since the 2021 coup, Myanmar’s military government has expressed renewed interest in pursuing a range of extractive developments, including the Hatgyi Dam, in a context of increased state violence and impunity. Details about the status of the seven proposed dams along the Salween, including Hatgyi, which would be built by Chinese and Thai actors, remain opaque and an ongoing source of friction.

Yet slow resistance persists and is reshaping the conditions of development over time. This reflects that, under authoritarian conditions, resistance and activism can produce incremental change and improvements, rather than immediate and overt change.

• • • • • • • • • •

This post is part of a series of essays highlighting the work of emerging scholars of Southeast Asia published with the support of the Australian National University College of Asia and the Pacific.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss