In the early 20th century, those Dutch residents in Indonesia who supported what became known as the Ethical Policy spoke of the debt of honour which the Dutch owed Indonesians, and especially Javanese, for the exploitative policies the Dutch had implemented in the 19th century.

The ethical school advocated three key policies which they deemed essential in order to deal with what they thought was the problem of overpopulation in Java. These were improved irrigation in order to boost agricultural output, better access to education to enable Indonesians to take up jobs outside the rural economy, and also land settlement outside Java (transmigration). These policies were also emphasised by the technocrats advising President Suharto from 1966 onwards, who quickly saw the need for increased agricultural output, improved access to education and greater movement of population around the vast Indonesian archipelago in order to increase economic growth and improve living standards both in Java and elsewhere. By the late 1960s, Indonesia was able to access aid from both the Netherlands and other western powers who, for a variety of reasons, supported the Suharto regime and wanted to encourage the rapid development of the country’s economic potential.

It is striking that neither advocates of the Ethical Policy after 1900—nor the technocrats who from 1969 onwards drew up and implemented the five year plans under Suharto—advocated redistribution of land or other assets; their emphasis was on exploiting both land and mineral assets, mainly outside Java.

The economic achievements of the Suharto era are well known. The reasons for the strong economic growth performance in the decades from 1967 to 1997 and the consequences for living standards in Indonesia continue to be debated, but a consensus has emerged that economic growth over these decades was higher than that achieved in the three decades from 1901 to 1931, when the full force of the global depression hit the colonial economy. By 1997 the living standards of most Indonesians had improved compared with both the early post-independence years and the colonial era. Most Indonesians had a better diet, were better educated and were moving in greater numbers into non-agricultural employment, and more were also circulating around the country, and abroad, than was the case before 1941.

But Indonesia was still considered only a lower middle income country by the World Bank in 1997, and in 1998 there was a steep decline in per capita GDP. Recovery was slow, and per capita GDP only surpassed the 1997 level in 2004—seven lost years in terms of economic growth. Since 2004, economic growth has been reasonable, and Indonesia has managed to move into the upper middle income group, although still below Malaysia and Thailand. Now the government aims to become a high-income country by 2045. Many doubt that will happen, but if it does, it would seem that Indonesia in 2045 will have about the same per capita GDP in real terms as Bulgaria today. This is not perhaps a great achievement, given the high expectations of those who fought for independence between 1945 and 1950.

In the UK, which had the largest colonial empire in 1913 in terms of both area and population, there are many debates now raging about the consequences of British colonial rule for the former colonies, in Asia, Africa and also the Caribbean, where the vexed issue of the impact of slavery is still bitterly contested. Demands for “restitution” are often heard, and very large numbers are often bandied about regarding the exact amount of such compensation.

In his recent article at New Mandala, Pierre van der Eng mentioned the work of Utsa Patnaik, whose conclusions about the “drain” of wealth from India have certainly attracted attention and criticism here in the UK, and elsewhere. Her arguments for the years up to 1914 are summarised in a 2021 article co-authored with Prabhat Patnaik. Although some of their numbers have been disputed, the critics of the British legacy in India surely have some valid arguments. The “home charges” compulsory remitted from British India back to London were substantial; around half went on interest payments, which were charged on the debts incurred for irrigation, railways and other productive investment.

But after 1920 a growing proportion went on military expenditures, which in large part were incurred to defend other parts of the British Empire rather than India itself. During the First World War India contributed hundreds of thousands of troops which were deployed in both Europe and the Middle East; even larger numbers fought for the British in the 1939–45 conflict. The costs fell mainly on the Indian budget. Apart from the small but very expensive expatriate bureaucracy, there were growing numbers of less well paid indigenous civil servants. Together with the expatriates, they kept the general administration functioning quite smoothly. But the focus of their work was hardly developmental in the sense in which we would understand the word today. The civil service which was bequeathed to independent India was, as the economist Angus Maddison claimed, “an autocratic Anglo-Brahmin structure created to run a static economy”. He argued that in the immediate post-independence era, there was little mobility between grades, and at the top level remuneration was largely in the form of non-monetary perks such as housing and social status, and also bribes. This was also true of civil services in other postcolonial countries in Asia, including Malaysia, Indonesia, Burma and the Philippines.

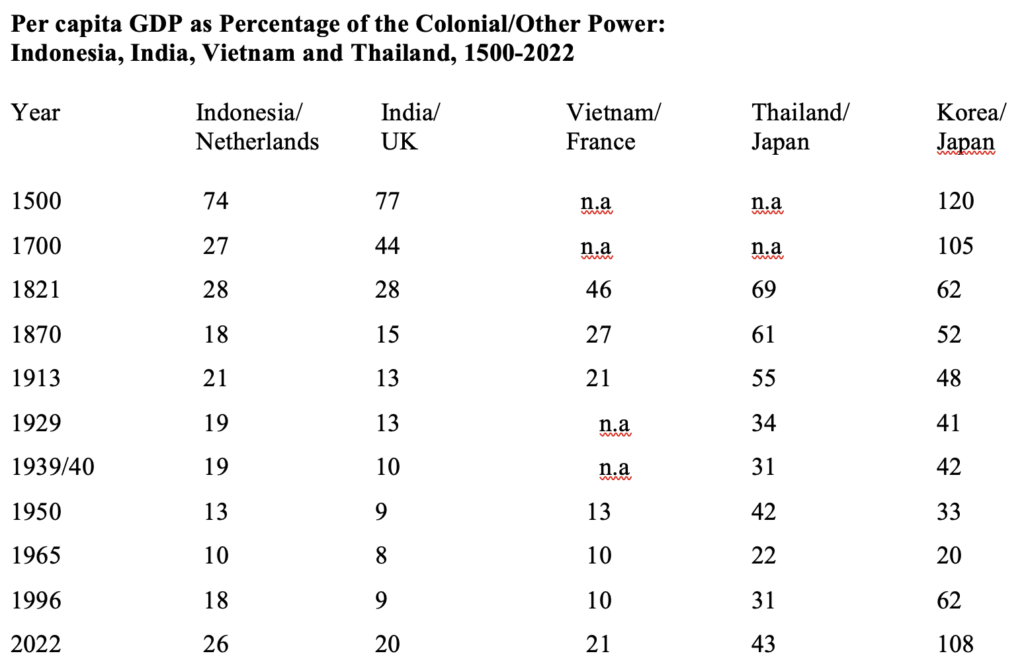

Maddison argued that countries such as India and Indonesia had a per capita GDP in 1500 which was around 70 per cent of that in Western Europe (see table below). Some think that this percentage is too high, but I think that it is probably about right, given what we know about living standards in much of Europe before 1700. I can find little evidence which shows that living standards in many parts of Asia were substantially lower than in much of Europe in the sixteenth and much of the seventeenth centuries, although by 1700 the Maddison Project data show large gap between the Netherlands and Indonesia, and a smaller but still substantial one between Britain and India.

Data for 1500–1700 are taken from Angus Maddison 2007, “Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD: Essays in Macro-Economic History” (p117); data from 1821–2022 are from the Maddison Project.

What does seem indisputable is that per capita GDP grew much faster in the UK than in India between 1700 and 1940. Many economic historians have argued that the industrial revolution in Britain occurred as a result of changes in British society which facilitated the development of modern science, and the growth not just of manufacturing industry but also key innovations in both land and sea transport and in finance.

Critics in India have argued that the home government deliberately prevented the industrial development of India, and encouraged de-industrialisation, especially in the textile sector. Whether “profits” remitted from India and from plantations in the Caribbean helped fuel the industrial revolution in the UK has also become a hotly debated topic in recent years. My own view is that most of the remittances from the British Empire to Britain before 1850 were invested in extravagant real estate and other forms of conspicuous consumption, but others disagree.

In Indonesia, the estimates compiled by the Maddison Project show that, in per capita terms, GDP fell relative to the Netherlands between 1820 and 1870. In part this fall resulted from growth in the Netherlands which resulted from trade with Indonesia. In their economic history of the Netherlands, Jan van Zanden and Arthur van Riel described the growth of a colonial complex in the Netherlands in which industries such as shipbuilding, sugar refining and textiles benefited from the growth of trade between the metropole and the colony. In addition, the remittances on government account from the colony to the Dutch budget were considerable.

In their economic history of Indonesia, van Zanden and Marks argue that the Cultivation System was perhaps the most extreme example of an extractive institution to have been introduced in any colony in the 19th century. After 1870, subventions from Indonesia to the Dutch government budget largely ceased, although private remittances to the Netherlands continued. Many Dutch observers justified the profits earned by Dutch companies as a fair return on capital allowing for the risks involved, but these assertions have been challenged by some studies. Frans Buelens and Ewout Frankema found that returns to foreign firms operating in Indonesia were indeed high in the decade from 1919 to 1928, but fell into negative territory in the 1930s. And after 1941 many foreign firms operating in Indonesia lost everything, even before the nationalisations carried out in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The GDP estimates of Angus Maddison and the Maddison Project (now based at the University of Groningen) show that between 1870 and 1940, per capita GDP in Indonesia grew faster than in India (until 1950 India refers to what became the three states of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh). Relative to the UK, Indian per capita GDP fell steadily from 1821 to 1940. The fall was less pronounced in Indonesia relative to the Netherlands; the estimates indicate that between 1870 and 1939, Indonesian GDP as a percentage of that in the Netherlands did not change much.

Does this mean that policies implemented after 1870 promoted growth in Indonesia in step with that in the Netherlands, and that accusations of “colonial drain” and “deindustrialisation” are unfounded? These are questions which deserve careful attention. My own conclusions are that while economic growth did occur in the seven decades till 1941 in Indonesia, the benefits of the economic growth in Indonesia over these decades were very unevenly spread between races, between regions, and within the indigenous population between social classes. Many indigenous Indonesians did not benefit much from the economic growth which occurred, and some may have been harmed by it.

I agree with the view of Willem F. Wertheim that by the last decades of Dutch rule, an indigenous middle class was emerging in Indonesia, employed in both the government and the private sectors. My own estimates from census data over the 1930s show that indigenous workers as a percentage of total workers employed in government and the professions were higher in Indonesia than in the Japanese colonies, or in the Straits Settlements and the Federated Malay States. At over 90 percent, the proportion was higher than in Burma, and only slightly lower than in Thailand in 1937, which was not a colony, and the Philippines in 1939 when it was already largely free of American control. Indigenous Indonesians were also a high proportion (84%) of all workers in commerce and trade in 1930, which was about the same as in the Japanese colonies and higher than in Thailand, Burma and the Federated Malay States.

Then there is the vexed issue of colonial extraction, which continues to bother researchers such as Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson. My own view is that it is not legitimate to regard all taxes as exploitative if the revenues were spent on public works, agricultural extension, health and education rather than the military and policing. Comparative data show that in the late 1930s, taxes and other government revenues on a per capita basis were lower in both India and Indonesia than in the various components of British Malaya and in Taiwan. But the budget data also show considerable variation across colonies in Asia in patterns of government expenditure; the Philippines stands out as the colony where expenditures on health, education, public works and agricultural development were high relative to those on policing and defence.

At the other extreme, Thailand (which was not a colony) spent most of the government budget on administration, policing and defence. Although Thailand did develop a rail network, it was known in the 1930s as the country without roads; road development in the north of the country had to wait until the 1960s. Yet in the last four decades of the 20th century Thailand forged ahead in terms of per capita GDP while the Philippines lagged behind, not just in terms of GDP per capita but also in terms of other development indicators.

Why was that? The sad fact is that many of the Filipinos who were educated in English-speaking secondary and tertiary institutions in the Philippines have sought employment abroad. According to recent World Bank data, remittances now account for a higher proportion of GDP in the Philippines than in any other Asian economy except Pakistan. If a country can’t export goods and services, it can always export people.

Another aspect of development in Asia over the last 50 years, and in some cases longer, concerns deindustrialisation. A surprising number of economic historians with an interest in globalisation issues seem to assume that deindustrialisation occurred not just in India, but in many other colonies in Asia, and even in parts of Africa. The evidence they produce is often scanty and usually relies on Indian data on textiles which has been challenged by Tirthankar Roy, among others.

If we look at the national income estimates broken down by sector, published by Richard Hooley in 2005 and Pierre van der Eng in 2010 for the Philippines and Indonesia, it appears that real value added in manufacturing and in related sectors including construction, utilities and transport grew quite fast between 1880 and 1940, even if these sectors did not increase their share of total GDP. And we should also bear in mind that in many Asian countries the data on agricultural output is often more complete than that for other sectors of the economy in the colonial period, so the figures on output of the non-agricultural sectors as a proportion of total output are probably under-estimates, relative to those for the agricultural sector.

By the 1930s, there was a growing realisation in both the Dutch and the French colonial administrations that industrial development would have to accelerate in both Vietnam and the more densely settled parts of Indonesia. I agree with Howard Dick, who has argued that between 1936 and 1941, after the Netherlands and Indies guilders went off the gold standard, the Dutch were implementing policies, including promoting foreign investment, which were intended to boost industrial growth.

These might have led to more rapid and balanced economic growth in Indonesia, and also improved living standards, had the recovery in the global economy continued into the 1940s, had the Netherlands managed to stay neutral in the 1939-45 conflict with Germany (as it did in 1914-18), and had there been no Japanese occupation of Southeast Asia. But in fact the 1940s were a dreadful decade, not just for Indonesia for much of East and Southeast Asia, as well as for the main colonial powers in Europe.

The UK, France and the Netherlands all experienced falls in per capita GDP between 1940 and 1945. The Japanese occupation inflicted great damage across Southeast Asia, as Gregg Huff has shown. In 1945 both France and the Netherlands were damaged by the German occupation not just in terms of economic output, but also in terms of national morale. Both nations seemed to feel that the loss of their empires would lead to further national humiliation and economic decline. The UK was a victor in name only, but many in the UK did grasp that the age of empire was over, at least as far as South Asia was concerned. Successive governments were slower to concede self-government to what had been British Malaya. No doubt its role as an earner of dollars was important, at least in the years from 1946 to 1950, but as the UK economy itself began to recover the dollar problem became less pressing.

It is a great irony of post-1945 economic development in Europe that those countries which lost their colonial territories in Asia between 1945 and 1957 began to flourish without them. The “30 glorious years” from 1946 saw impressive economic growth in both the Netherlands and France, and somewhat less rapid growth in Britain. Few argued after 1945 that the loss of India would be a great economic blow to Britain, and most economists would argue that the slower growth in Britain compared with France or the Netherlands was due to factors unrelated to the loss of empire. Romantic imperialists like Churchill were defeated at the ballot box in 1945, and Atlee’s government had no appetite for a bruising and expensive war in India which the British could not possibly win. Far better to cut lose, and let both India and Pakistan solve their own problems in their own way.

The GDP data would suggest that neither India nor Pakistan achieved impressive economic growth in per capita terms after 1950, although growth in India has accelerated after 1990. When the Conservatives regained power in 1951, very few thought that regaining the Indian empire was either possible or desirable, and through the 1950s and into the 1960s the British goal was to prepare as many colonies as possible for independence as quickly as possible. The Dutch were forced by American pressure to “liberate” Indonesia, although the conditions under which independence was granted were far from favourable to the new Republic of Indonesia.

Measuring "colonial drain" isn't a straightforward business

Colonial rekening: what does the Netherlands owe Indonesia?

How can we explain these numbers? In my view we need more research on British, Dutch and French colonies in Southeast Asia, with particular focus on the years from 1870 to 1940. The research should look at the impact of colonial policies not just on economic growth, but also on the distribution of the benefits of the growth which did occur by ethnic group, and region. To what extent did growing involvement in production for export benefit indigenous producers of export crops, as well as those working as wage labourers in large estates and mining operations?

A second issue, still largely unexplored in the Southeast Asian context with the partial exception of the Netherlands, is the impact of colonial remittances on the economies of the metropolitan powers. How important were they, and what impact did they have on economic growth in Britain, France and the Netherlands, or in the case of the Philippines, on the economies of both Spain and the USA?

A third issue concerns the implications of colonial policies regarding links with the global economy for post-colonial policies on foreign trade, exchange rates, foreign investment and movement of people? Today, the ten countries which form the Association of Southeast Asian Nations show huge variation in their policies regarding globalisation from Singapore at one extreme to Myanmar at the other. It is obvious that the policies they have adopted have affected economic growth and welfare within these countries, but to what extent are these differences the result of colonial legacies?

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss