This post is part of New Mandala’s month-long feature on Thailand’s 2007 constitution referendum.

Full-steam campaigning does not seem to be on the cards in Chachoengsao. Chaturon Chaisaeng did not turn up as promised at a discussion of the draft constitution held on August 1 at the Rajaphat University. He cancelled his appearance at 5 pm the day before, saying he had to go abroad. An observer, however, argued that Chaturon’s role in Thai Rak Thai (now Phalang Prachachon) had been greatly diminished. Since it was not sure for which political party his family members would run in the election, it was not advisable to vigorously campaign for the former Thai Rak Thai’s cause against the constitution.

Only about twenty ordinary citizens took part in the seminar that saw both the “yes” and the “no” vote options represented. Leaflets produced by the Constitution Drafting Assembly and Thai Rak Thai were distributed.

Image 1: Referendum leaflets

The remaining 200 participants were students. A lecturer told me, “They are not interested in the constitution but were ordered by their lecturers to come.”

Meanwhile, the provincial Constitution Drafting Assembly branch has erected small billboards at a very limited number of intersections.

Image 2: Small promotional billboards

Often, the boards are hardly visible to passing motorists. On August 2, I traveled to Bang Khla district to hear a representative of the provincial Constitution Drafting Assembly advertise the constitution in the monthly meeting of district section chiefs, kamnan, village headmen, and local governments.

Image 3: Administrative meeting

Surprisingly, his rather unstructured talk ended after only five minutes. Even the hosting chief district officer (nai amphoe) seemed to be surprised and asked “kae ni rue” (only this much?).

After the Constitution Drafting Assembly delegation had left the meeting, the nai amphoe talked a little more about the constitution. Only a few days were left until the referendum. As everybody knew, the country was in bad shape. Factories had to close; the strong baht caused problems for exporters, including the closure of factories. Other countries were hesitant because they saw Thailand as lacking in democracy. Therefore, Thais had to stop their quarreling. One way of doing this was holding an election. Some village headmen had told him they did not want to vote in the referendum. The nai amphoe asked them to reverse their decisions and also urge their fellow villagers to cast their votes. Variously, he emphasized that he was only urging them to vote, while it was up to the individual whether he or she would vote for or against the constitution. A turnout of 50% would show the world that Thailand was on its way back to democracy.

The nai amphoe expressly asked the kamnan and village headmen to bring villagers to the polling stations. This was not against the law. His statement reflected what had been said by national election commissioners, namely that–unlike in general elections–providing transportation for voters in the referendum was legal. The chief district officer also called on those who wanted to vote in the referendum to raise their hands. All hands went up. He followed this up with the question, “And who would vote for the constitution?” Again, all hands seemed to go up. When he asked, “Who would vote against the constitution?”, two people raised their hands. The nai amphoe himself did not seem to take this exercise too seriously.

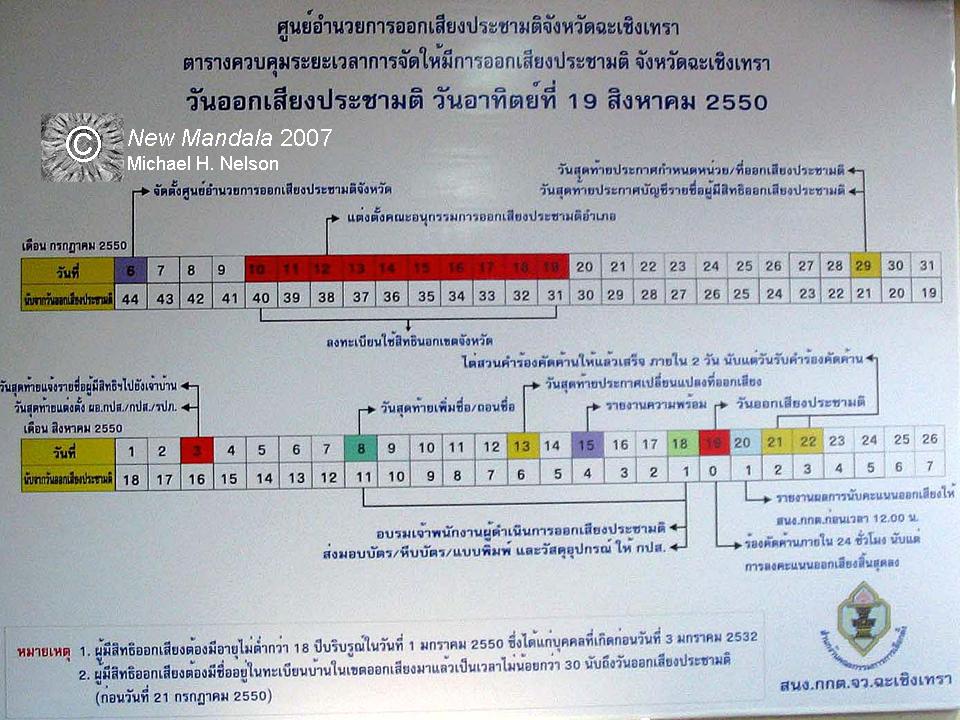

As for the process of organizing the referendum, the provincial election commission has entered into its routine process, as fixed in the referendum calendar issued by the Election Commission of Thailand.

Image 4: Official referendum calendar

Manuals for voters and polling station officials have arrived already. On August 1, the Provincial Election Commission’s district-level subcommittees, composed exclusively of permanent civil servants, were called to a meeting, where staff informed them about the referendum calendar and the budget available for doing their work and buying polling station material. Since it did not cover a clock and a national flag, participants were asked to provide these vital pieces locally. The office had also erected a huge billboard opposite the provincial hall advertising the referendum.

Image 5: Referendum billboard

However, to the Provincial Election Commission, the referendum is only one task among others that have to be fulfilled. There are, as I noted in my first post about Chachoengsao, a large number of local elections that require attention.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss