For the sake of parsimony, most analyses try to pinpoint the key factors behind Thailand’s enduring conflict. Albeit insightful, they tend to shed light only on parts of the puzzle. In order to gain a better understanding, this essay adopts an old-school political economy’s troika of interests, ideas and institutions as the analytical lens. It points out how Thailand’s Gordian knot is inextricably linked in three dimensions. Any reform can hardly be fruitful unless it tackles these three dimensions altogether.

Interests: Material Benefits at Higher Stakes

The bulk of existing explanations focus on the struggle of contradicting interests at street level, identifying the Democrat Party in tandem with royalist and bureaucratic elites on the anti-election side, and the incumbent Pheu Thai Party and Thaksin’s political and business allies on the other. At a sacred level, there is unspoken anxiety over the royal succession. Resembling the twilight years of King Chulalongkorn in the early twentieth century, great reigns inherit a sting in the tail and raise the stake of the palace circles. Although sharing the interest-based perspective, some observers point to regional and class factors. While Thaksinite parties hold the populous north and north-east, the Democrats dominate inner Bangkok and the south. Class also matters. The anti-democratic protests led by the middle classes are not exclusive to Thailand, but are taking place in various developing countries, in fear of populist leaders who allocate larger pieces of cake to the poor (see, for example, here).

Assuming partisan politics and pork-barrel spending in a country where election is not the only game in town, it makes complete sense for rational losers to stage the marches. Yet, interests are only part of human motivation, and they themselves are also shaped by ideology, given the fact that even those gaining from Thaksin’s policies also joined the protests.

Ideas: Public Choice Versus Public Choices

A power struggle is also the battle over people’s minds. During an uncertain period, in particular, recent theories suggest that ideas play a crucial role in making collective actions possible and plausible.

As with countries in the ‘third wave’, democracy and its underlying principles have gradually settled in Thailand since the 1980s. However, it is by no means the only major ideology. Thailand has witnessed the tussle between democratic values, central to which is majority rule, vis-├а-vis the ‘individual-morality worldview’ underpinned by the Buddhism-neoliberalism duet.

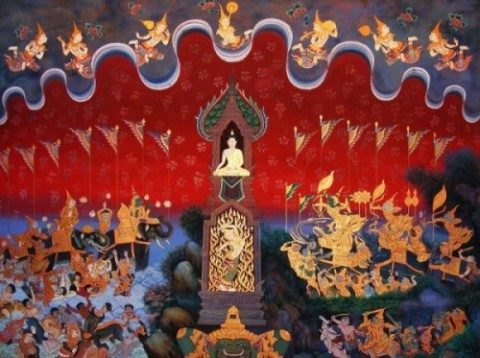

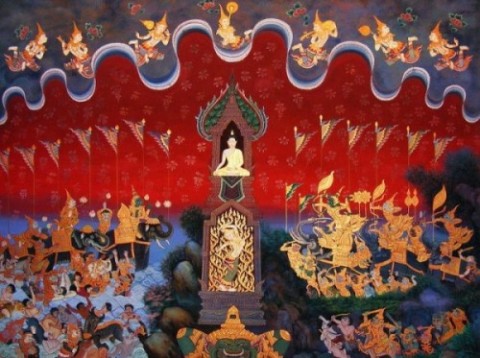

Buddhism has resided in the land of smiles for many centuries. The prevailing convention provides the unit of analysis for probing into matters of life and society by reducing them to a matter of individual morality. Human suffering boils down to individual craving, notably greed. Immoral individuals are those who cannot resist their own greed. Moral people can, and therefore do, bring about good social outcomes, just as all the past kings did to ‘non-colonised’ Thailand.

Resting on the Public Choice Theory, which considers political actors to be self-serving, utility-maximising individuals and puts corruption as the universal plague of developing countries, neoliberalism has become strange bedfellows with Thai-style Buddhism and mutually reinforced such a worldview among younger generations. Still, rather than the fight of all self-seeking individuals, the Thai narrative deems politics to be the fight between moral and immoral persons. Having been ingrained with Buddhism when young and installed neoliberal values when studying abroad, it shouldn’t be a surprise that most Thai technocrats take the individualistic worldview as the only way to interpret the world. In this light, the observation sociologist Norman Jacobs made in 1971 in Modernisation Without Development still holds true:

In Thai thinking, corruption is the cause of inefficiency, social disorganisation, and almost every other possible ill that can befall the social system. But Thais do not believe that corruption is in any way the consequence of the system’s patrimonial institutions; rather, they believe it is due to the failing of specific individuals within the system to resist temptation. Conveniently, individuals can be replaced, and the patrimonial system can be preserved and even revitalised merely by purging the tainted from the ranks of the worthy decision-makers. Because corruption is not considered an institutional problem, the occasion for a purge of corrupt individuals is not an occasion for a possible re-assessment of the (patrimonial) system itself.

Tyranny of the majority and corruption led by Thaksin’s alliance may be a valid criticism. However, negligence of the patrimonial and oligarchic system in their causal attribution, the search for ‘good individuals’ has become the focal point or single-issue politics of the current demonstration. Further, unlike advanced democracies, there are more varieties of political tool available in transitional democracies like Thailand to topple immoral leaders, including coups d’état, party dissolution, and judicial activism. With ongoing political skirmishes, morality and majority, as well as Public Choice and public choices, are increasingly hostile here.

Institutions: Where Institution Means Person

Institutions come to complicate things even further. On the one hand, contrasting interests and ideas have been institutionalised. Constitutional and electoral legitimacies are set for a collision course under a zero-sum regulation. The interests of the military, the judiciary and high-ranking technocrats have been enhanced by the 2007 Constitution. The empowered Constitutional Court is functioning as the spearhead in tapering the cabinet’s policy options. Regarding ideology, while the state schools preach the virtues of individual morality, with the utopia/dystopia illustration of past monarchs against corrupt politicians, the Democrat-aligned Blue-Sky and the Red Shirt-aligned Asia Update television channels provide differing interpretations into daily political affairs tailored-made to viewers’ gut instincts

On the other hand, the country’s conflict-resolution mechanisms have become more personalised over time. That a very generic term like ‘institution’ specifically means ‘royalty’ in Thailand speaks volumes. The highly acclaimed role of King Bhumibol in summoning two power brokers and ceasing the 1992 Black May well reflects how Thailand had impinged upon informal ways of forging a political compromise. All the mass uprisings since then, either pro- or anti-Thaksin, have called for the King – or the King’s men, or at least the King’s signal – to defuse tensions. From ringing the palace’s bell in the thirteenth century, modern Thais occupy the streets to plead for royal mercy as if no third-party bodies had ever developed in the past centuries.

Loosening and Untying the Knot

In a nutshell, Thailand’s contemporary Gordian knot is multi-dimensional. Effective reform needs to address this interconnected troika. Loosening the knot demands the institutionalisation of conflict-resolution mechanisms to enable the symbiosis between traditional and electoral interests. The key question is how to alter the role of the establishment from staying in an ‘ambiguous place with ubiquitous power’ to a ‘well-designated arena with a well-defined authority’. Modelled on the British House of Lords, one workable solution is making the Senate fully appointed – on the condition that its power in relation to the Representative House is clearly circumscribed.

Untying the knot is more challenging. Thai politics has been careening between the populist and oligarchic modes, as characterised by Dan Slater, a Chicago political scientist (see here). Following the ‘lesser evil’ approach, all impactful socio-economic movements in past decades had to ally with either the populist–immoral or the oligarchic–patrimonial leviathan. Devolution is therefore instrumental in grounding substantive democracy. An additional imperative includes the reinterpretation of Thai-style Buddhism into a more pluralist, structuralist and democratic-friendly fashion. Ideas are weapons; institutionalised ideas are weapons of mass deconstruction.

Veerayooth Kanchoochat recently received a doctorate from the University of Cambridge. He has been teaching political economy at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS, Tokyo). He can be contacted at [email protected]

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss