A proposal to abolish direct elections for local government heads (Pilkada) in Indonesia has resurfaced after President Prabowo Subianto reiterated the idea in a recent speech at the Golkar party’s anniversary event. Prabowo suggested that regional heads could still be elected democratically through local councils (DPRD), without “wasting” public funds. Golkar Chairman Bahlil Lahadalia welcomed the proposal, arguing that democracy should be inexpensive, and that direct Pilkada contradicts this vision.

This debate is not new. After the party coalition that supported Prabowo’s unsuccessful July 2014 presidential campaign legislated to abolish direct Pilkada in September that year, outgoing president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s administration issued a presidential regulation in lieu of law (Perppu) that reversed that abolition. Yet the push to return to the pre-2005 system—of having local executives appointed by local legislatures (DPRD)—has persisted since then. Prabowo and his Gerindra party have long opposed direct Pilkada as part of a conservative, centralising political vision embodied in their long-professed ambition to restore Indonesia’s constitution to its “original” 1945 version.

But abolishing Pilkada is not just a solution to high-cost politics. Rather, elite narratives in opposition to local polls are driven by pragmatic drive to assert control over local executive government, and a general fatigue with electoral competition. Indeed, the “costly Pilkada” phenomenon is rooted in two interrelated elite behaviours: tolerance of opaque political funding and reluctance to reform inefficient electoral administration. Instead of addressing these structural problems, some political elites now purpose abolishing direct local elections altogether. This move reinforces the suspicion that the issue is not fiscal efficiency, but political convenience—and opportunism—on the part of a governing coalition that, as our analysis shows, would be well-placed to influence the appointment of local leaders by local legislatures.

Direct Pilkada are costly because of elite behaviour

Many politicians argue that direct Pilkada are “costly”, both in terms of the costs to the state of administering elections management and political expenditure. But high costs are not inherent to direct elections. They are largely the product of the choices of elites, who remain reluctant to make urgent reforms to the electoral system and tolerate opaque and illegal political financing.

Political financing in Pilkada is marked by significant discrepancies between reported and actual expenditures. According to Indonesia Corruption Watch, the average reported campaign donation income of gubernatorial candidates is around Rp9 billion (US$532,410), while mayoral candidates report only Rp 1.6 billion (US$94,650). Reported expenditures are similarly modest.

Yet these figures are widely believed to underestimate real campaign spending. Research by Arya Budi, Mada Sukmajati and Wegik Prasetyo on the 2018 Madiun mayoral election illustrates this gap. One candidate officially reported spending Rp841.9 million. However, after shadowing the campaign and conducting in-depth analysis, the researchers found the actual expenditure reached approximately Rp7 billion. The difference came from off-the-books transactions, including payments to political consultants, nomination costs, and witness (saksi) fees.

Illegal transactions further inflate political costs. Perludem has mapped three layers of campaign spending in Pilkada: first, reported legal expenditure such as rallies and campaign materials; second, unreported but legal expenditures like consultants, surveys, and campaign teams; third, illegal transactions such as vote and candidacy buying. The last category is particularly costly. As Marcus Mietzner notes, candidates often must pay parties to secure nominations (this is in order to meet the legal requirement to secure a nominating coalition of parties that hold at least 20% of seats in the local DPRD). In addition, vote-buying, a persistent feature of post-Reformasi politics, significantly increases campaign expenditures.

The high cost of organising direct Pilkada also stems from an overly lengthy, layered, and administratively duplicative electoral administration that elites have been reluctant to reform. A direct Pilkada involves lengthy stages, requiring temporary staff to be recruited by local electoral commissions (KPUD) up to seven months before polling day. According to Perludem, many of these temporary workers receive monthly salaries despite having low workloads during stages such as candidacy verification and campaign periods. Moreover, because voter databases are not fully integrated, election authorities must still conduct door-to-door voter verification, one of the most resource-intensive stages of the process. At the voting and tabulation stages, extensive logistics are required, involving national, provincial and municipal levels of election management bodies. This institutional design inflates budget allocations for elections unnecessarily.

After Constitutional Court Decision 135 in 2024 mandated that national and local elections should be conducted separately, opportunities for efficiency have emerged. For instance, at the local level, executive and legislative ballots could be combined, since both contest are held simultaneously. Integrating these ballots would significantly reduce the volume of printed materials, ballot papers, and other logistical components required for polling day. Fewer ballot types would also simplify polling station procedures, reduce burdens on poll workers, shorten counting times, and lower the risk of invalid votes. Logistical transportation and storage costs would also decline accordingly.

However, inefficiencies persist so long as elites show little political will to initiate comprehensive electoral reform. Proposals for digitalisation, ballot simplification, and institutional streamlining have long been discussed by civil society, yet remain largely unimplemented.

Not rational reform, but a pragmatic shortcut

The call to return to indirect Pilkada is increasingly framed as a rational response not only to excessive political costs, but also to local conflict and central–national tensions engendered by direct election of local executives. Leading figures within the governing coalition have articulated these positions. Prabowo has repeatedly emphasised the need for vertical political cohesion between the national and subnational level. Golkar’s Bahlil has argued that governance would simply be easier without Pilkada, while PKB Chairman Muhaimin Iskandar highlights the financial burden of competition. These statements are a common premise: local political contestation is treated as a burden to be eliminated, rather than a democratic arena to be improved.

On what’s lost when the Dutch East Indies is recalled as a time of picturesque sophistication

Instagramming colonialism in Surabaya

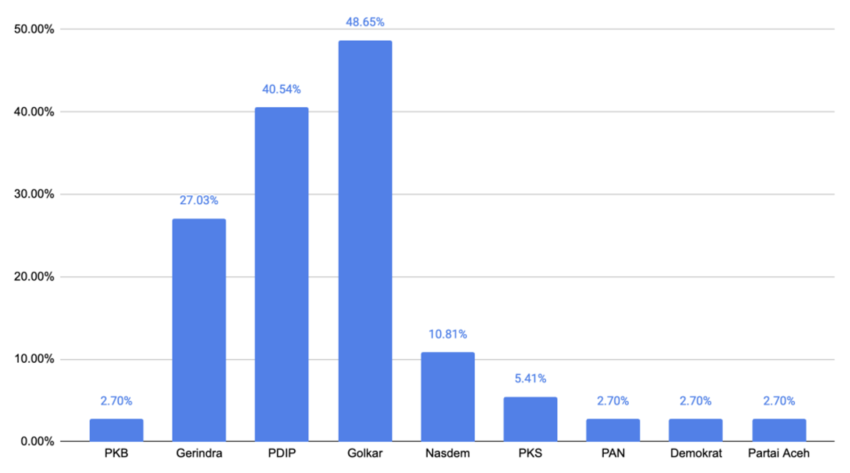

Under a direct Pilkada system, legislative dominance does not automatically translate into control of the executive. Voters retain the power to choose governors, mayors, and regents independently. But if the selection of regional heads were transferred to DPRDs, legislative arithmetic would become decisive. For instances, in some provinces like South Kalimantan and Riau, where KIM Plus holds more than 80% of seats, indirect elections would institutionalise executive appointment within a dominant bloc. Executive selection would effectively become an internal coalition process rather than an open contest.

This structural advantage suggests that the proposals to abolish Pilkada are closely related to the ruling coalition’s strategic interests, and are not merely about saving public funds.

Recentralisation and its democratic consequences

Abolishing Pilkada means reinforcing a broader centralising vision. If regional heads are selected through legislatures dominated by nationally aligned parties, vertical political cohesion becomes easier to maintain. The executive branch at the regional level would be less directly accountable to voters and more dependent on party structures and coalition arrangements tied to the centre. Such a move risks weakening regional autonomy and reversing one of the core achievements of Reformasi: the direct accountability of local leaders to their citizens.

Direct Pilkada have served as an arena for elite circulation and leadership regeneration since their introduction in 2005. They have enabled local figures to build independent legitimacy and occasionally challenge established party hierarchies. Removing this mechanism would narrow pathways for leadership renewal and push party politics toward a more closed, elite-driven model.

If the real concern is cost, the rational solution is reform, not retreat. Strengthening campaign finance enforcement, simplifying electoral design, and embracing digitalisation can improve efficiency without sacrificing democratic accountability. Democracy may be costly, but the cost of abandoning democratic competition may prove far greater.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss