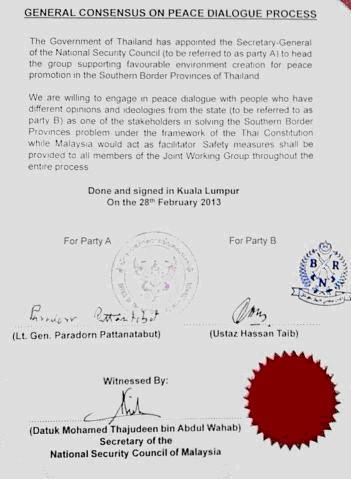

Fig. 1: The General Consensus document signed on 28 February 2013)

The nascent peace dialogue between the Thai government and “people who have different opinions and ideologies than the state” (the actual wording of the document; see above) is gathering momentum in Thailand. Crucially, and contrary to many commentators’ initial impressions (including my own), the overtures and first steps in this process have been skilfully handled. Thawee Sodsong, the head of the Southern Border Provinces Administration Centre, a man widely seen as pivotal in this process, has hitched his rising star to what is being dubbed the “KL Process” (thus named because the document was signed in Kuala Lumpur on 28 February this year). The second formal meeting of this process is underway in Kuala Lumpur today, and the early signs are positive. The Thai government, under the direction of Thawee and National Security Council chief, Paradorn Pattanatabut, has carefully pursued a strategy that negotiates some of the shortcomings of past processes.

For starters, putting out ‘a piece of paper’ from the outset commits Thailand; this was a bold and prescient move. In what is essentially an agreement to talk (officially the 200-word document is entitled, “General Consensus on Peace Dialogue Process”), Thailand is putting a marker down that claims both its stake and ascribes the significance of its political investment in the KL Process. Unlike past attempts, Thailand’s official representation is manifest from the beginning; in this case the National Security Council has an unambiguous mandate.

Despite previously stated antipathies on both sides towards Malaysia playing a mediator role, this is precisely what has occurred. In what appears to be an accommodation between former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra and Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak, the groundwork for this process relied heavily on Malaysian security agencies’ familiarity with exiled elements of the militant resistance group, Barisan Revolusi Nasional (The National Revolutionary Front or BRN).

What’s remarkable about the process to date is the fact that the Thai government has made all the right moves and seems to have a game plan. If successful, an inked peace accord would be a firm foothold for Thaksin’s return to Thailand. Meanwhile, it has become increasingly clear that BRN’s four representatives – all known entities from past peace processes – are swimming in deep (deepening?) waters. Expert commentators on the “Deep South” (as Thailand’s three southernmost provinces of Yala, Narathiwat, and Pattani are sometimes referred) have expressed doubts over whether this delegation truly represents rank and file BRN combatants. These views betray their sources, which are predominantly Thai military officials and exiled members of other Patani resistance groups. Such assertions appear at face value to be correct, but closer inspection reveals that key developments have been ignored. For instance, the return and reintegration of 93 former BRN combatants from Malaysia to Thailand in September last year, spearheaded by Fourth Army Commander Lt-General Udomchai Thammasaroraj, reflects a shift away from a purely militant focus to what one person close this fledgling reintegration process described as “jihad memikiri” or a revolution in resistance thinking. Recent attacks, including the widely reported attack in Bacho district, Narathiwat last month, strongly suggests that BRN combatants are struggling to execute attacks that demonstrably weaken their adversary, and instead have become increasingly costly in terms of manpower and public sympathy. Whereas many prominent commentators point to an increasing professionalism and organization of militant resistance activity, BRN’s current tactical capability must be said to be the stuff of abject speculation.

The General Consensus document has several salient components worth highlighting. Firstly, the acknowledgement of BRN as the prime mover amongst Patani resistance groups is a fact that has eluded many academics and commentators focused on this part of Thailand; namely that BRN is not divided based on a split that occurred in the 1980s (i.e. Coordinate, Congress, and Ulama factions of BRN). The fracture that occurred in the 1980s does not reflect the reality today, which is hierarchal and sophisticated from an organizational perspective. The second salient feature of the General Consensus document is that it goes against the frequently accepted rhetoric that former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra is a peace spoiler. The KL Process already shows more promise than all previous attempts, including efforts made under the administrations of Surayud Chulanont and Abhisit Vejjajiva as of 2006. The openness of the current process is reflected by the clamour and interest amongst civil society groups, local political interests, and issue-based advocacy groups to become involved. The General Consensus document calls for the establishment of a Joint Working Group (JWG), which has already become the subject of speculation in the lead up to and during deliberations last week at the second formal meeting of the parties. The composition of the JWG has already captured the attention of the Thai media and many layers of both civil society and political groups in Thailand’s Malay-speaking provinces. It is not clear how much agency BRN’s four representatives have demonstrated in appointing or vetting the composition of this group, which is an early warning sign. Recent reports have indicated that other exiled resistance groups including relics of BRN’s splintering in the 1980s and prominent factions from the Patani United Liberation Organization or PULO will be appointed to act on behalf of Party B, which is phrased as “people who have different opinions and ideologies than the state” (NB. Party A is the Thai government).

As mentioned above, the ability of BRN to effectively negotiate has been questioned, with commentators usually remarking that it remains to be seen how the rank and file of the insurgency respond. It is worth pointing out that the profound culture of secrecy and highly coordinated nature of militant resistance in Thailand’s far southern provinces are strongly suggestive of a substantial degree of command and control. Perhaps what really remains to be seen is whether BRN is willing to compromise; put another way, it remains to be seen if what the Thai government puts on the table is attractive enough to precipitate a de-escalation of violence and a roadmap to a peaceful resolution of Thailand’s longest running internal conflict. It is stating the obvious to point out the intrinsic fragility of the process at hand, but again, the Thai government has carefully traversed inter-group disaffection by first acknowledging BRN, instead of recruiting the more outspoken (and therefore prominent) resistance group, in this case PULO. And if recent reports are anything to go by, acceding to PULO’s splinter factions’ ardent desire to be involved, the Thai government has displayed tact and finesse.

In terms of next steps, there are several developments worth watching. The first and most critical set of milestones will be reciprocal confidence-boosting measures. Leaving aside who goes first, the parties will have to craft credible trust-building measures, including the inclusion of other stakeholders rather than just militant and exiled resistance groups (e.g. local political interest groups, civil society organisations, local ulama, and women’s led organisations). This may necessitate the establishment of panels and study groups (or possibly a secretariat to act as a clearing house for local grievances, demands, and proposals) under the JWG. From a purely tactical standpoint, both sides will most likely demand cessations in different forms, including but not limited to a ceasefire (e.g. limited by duration, geography, or both) and the repeal (temporary or permanent) of various legislation and/or powers of arrest, detention, due process, immunities for security officers, and fundamental freedoms that are circumscribed under the provisions of both the Emergency Decree and Martial Law (both of which remain in force throughout the three southernmost provinces). It is also possible that reintegration of several hundred undocumented ex-combatants residing in Malaysia becomes a confidence-boosting measure.

Fig. 2: A logo developed by a Facebook user; note the paper crane reminiscent of Thaksin’s air-drop of 100 million origami cranes in 2004; and the dual spelling of “Pat(t)ani”

Malaysia as mediator, not to mention the parties, will have to be wary of the KL Process turning into a travel and money-making venture as so often happens (e.g. the Juba Peace Process in 2006-08). Another concern is the need for proper counsel for the resistance groups and other representatives comprising Party B. It will become clear as the true leadership of BRN proves itself reluctant to emerge from the shadows that BRN’s representatives lack negotiation experience. This could have an indirect spoiler effect. How the parties open up the negotiation space will be determinative, especially representatives from civil society and political interest groups from inside Thailand, and resource-persons and mediation-support institutions from outside (a useful illustration of this point will be how the “safety measures” mentioned briefly in the General Consensus document are negotiated). Put simply, Party B, especially BRN, will need assistance in negotiation, and this should be apparent to Malaysian mediators and Party A.

The timing for a constructive dialogue on peace in the southern provinces of Thailand has ripened. All the early signs are there and the Thai government is making the rights moves so far. There are enormous challenges ahead and the mortal risks that are likely to flow from a failed or unfair accord warrant close attention over the coming months. How the parties engage the Malay-speaking people of this part of Thailand, their leaders, and opinion-shapers will be critical. The KL Process has made promising overtures, and the weeks and months ahead will tell us if both sides can sustain this constructive spirit.

James Bean is a PhD candidate with The Australian National University’s School of International, Political, and Strategic Studies. Email: [email protected]

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss