Across Indonesia, Pemuda (youths) with their university jackets are mourning the death of democracy. Their vigil was a colourful assembly of yellow, green, and red that on April 11th turned into a violent disharmony. Their eulogy condemned the agenda of election-delay and President Joko Widodo’s flirtation with the concept of a third term to satisfy his political impulse.

Indonesia might still have its 2024 general election on February 14, but as Lady Macbeth put it “Th’ attempt, and not the deed, confounds us.” The recurrence of nationwide demonstrations by Pemuda during Jokowi’s administration illustrates a tragedy of a Macbethian proportion:

Indonesian democracy corrupted a decent person, turning him into a despot; the Pemuda check and balance this despotic tendency, yet the people keep electing a despot to lead the nation. But who is responsible for the death of Indonesian democracy? Was this an unintended consequence of Jokowi’s ambition to better Indonesia and cement his legacy? A product of power-seeking oligarchs surrounding Jokowi that led him astray? Or a product of Indonesia’s flawed democracy that possesses conflicting aspirations for freedom and a desire to be led?

William Shakespeare’s Tragedie of Macbeth ask similar questions, interrogating the concept of individual agency. Reflecting on Macbeth allows us to unpack the dilemma of agency when evaluating the culpability of a despotic behaviour––exposing the tension between individual volition, groupthink, and systemic pressure. While Macbeth clearly put a dagger into King Duncan, Shakespeare’s whodunit play never answers who was responsible for killing Duncan: Was he coerced by Lady Macbeth and her ends-justify-the-means outlook, or was he entrapped by the three-witches’ foreshadowing of his destiny? The latter allows Macbeth to raise a defence of diminished responsibility: he was not guilty of a crime because he did not act on his own volition, manipulated by forces beyond his control.

The story of Jokowi’s ascent resembles that of Macbeth: it was a parable of a person who refused to stay in his allotted place, overturning the natural order of a system. Jokowi’s predecessors were privileged to assume their position: Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono was an accomplished military general and former minister; Abdurahman Wahid was a leader of the Nahdatul Ulama, the largest Islamic organisation in the world; Megawati was a revolutionary figure who carried the Sukarno’s name; Suharto came from the Indonesian military, and Sukarno was an intellectual revolutionary. Jokowi did not possess worldly intellect nor the privileges of his predecessors; his election disrupted the usual path to power. Before him, being a successful furniture salesman and Mayor of Solo would have been insufficient to be elected as the president of the third largest democracy in the world. His exception led some to invoke the metaphor of Petruk Dadi Ratu, a Javanese lore about a king who rose from an ordinary people with no support from political elites, which raised the question of agency: was he a king or a puppet?

Pemuda protesting the agenda for a delayed election in West Sumatra on April 11, 2022. (Image by Rhmtdns on Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Thirty years of Suharto (1968–98) habituated thinking of a leader like a king, which instilled the notion of control as understood by the Javanese conception of kingship: A king is a candle within which the divine lights radiate and must be obeyed. Under a similar logic, establishing control became Jokowi’s preoccupation between 2014 and 2017. To consolidate power, he made a deal with established forces––the Indonesian military and other elites. By 2017, Jokowi demonstrated that he could preserve a significant degree of agency by giving concessions to elites, humiliating his dissenters via reshuffling cabinets, and balancing Megawati, the leader of the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), in a limited way.

The return of student protests and the government’s response have are reminiscent of the era of authoritarian rule

Indonesian protests point to old patterns

We could be upset with him, but the Indonesian political system makes a fully accountable figure an impossibility. Jokowi’s down-to-earth and social media savvy profile was insufficient for him to lead. The system prohibited him from campaigning as an independent, requiring him to be nominated by a political party, leading him to form an alliance with the PDI-P. PDI-P then worked to restrain his manoeuvre: he was required to cater to the interests of political patrons, which led to the polarisation of loyalty of his elites. The Indonesian democracy forced Jokowi to make a Faustian bargain.

But to argue that Indonesia’s democracy was faulty by design obscures the complicity and culpability of the oligarchic forces and Jokowi in killing the democracy.

Realising that challenging the oligarchic forces was futile, he instead harnessed them. A figure closely resembling Lady Macbeth is probably Megawati who, despite her emergence out of revolutionary events in 1998, geared PDI-P to propose laws that took power from the people: the abolishment of direct election and a defamation law for criticising the president. The three witches––nationalism (represented by the military elites), Islamism (represented by the savvy political ulama), and clientelism (represented by rent-seeking business oligarchs)–––also tempted Jokowi to tolerate undemocratic acts as a means to secure power. Throughout his presidency, he performed acts of loyalty to these forces. He put on a military uniform and vowed not to apologise to the victims of military abuse during the period of pro-nationalist, anti-communist pogrom to demonstrate his nationalism. He put on his cap and embraced the Islamists to win an election. He engrossed himself with Lady Macbeth and the three witches, which made him not just complicit but culpable.

Jokowi is no puppet, but as a king does he possess agency?

Joko Widodo was given a green turban by K.H. Maimun Zubair before attending the “Rapat Umum Rakyat” at Gelora Bung Karno, Jakarta. (Public domain. Government of RI on Wikimedia Commons)

Between 2017 and 2019, Jokowi’s preoccupation shifted from consolidation to anointment as a performance of political power. This was not just performative, it was an assertion of kingship. One of the most interesting cases was the replacement of Gatot Nurmantyo, then Chief of TNI (Panglima). Like Banquo in Macbeth, Gatot was Jokowi’s first ally who helped consolidate his power but soon deserted him by showing ambition to contest him in the 2019 general election. Jokowi hastened his replacement, and anointed Hadi Tjahjanto, as Panglima. By rights, no one would have predicted Hadi would get the spot. What Hadi lacks in experience he made up in loyalty, which was seen within TNI as a flagrant case of civilian interference into military politics. This sent a clear message: anointing was a kingly move.

The melancholy of the Suharto’s authoritarian era soon took over. In his second term, he purged critics and worked to eliminate balancing forces altogether by bringing Prabowo into his administration. Getting closer to the ideal of achieving harmonious political order as understood by the Javanese, in the process he put a dagger into a sickly Indonesian democracy.

Although his goal for development was well-meaning, the means was not. Jokowi is an ambitious president, reminiscent of Sukarno’s worldly goals but with Suharto’s restrained rhetoric. Jokowi has embarked on concretising many ambitious infrastructure projects, far beyond the complacent Yudhoyono. Yudhoyono chose to be a sitting duck. After much cajoling, he allowed reform-minded ministers such as Chatib Basri and Sri Mulyani to embark on various economic projects that got Indonesia out of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, but as soon as Indonesia’s economy stabilised he put a stop to the reform process. Jokowi is the opposite of Yudhoyono. He was ambitious in his first term, and got even more ambitious in his second. He is now moving the capital, an act that not even Suharto could realise. To fulfil his many ambitions of equal development, he justifies the means.

But was he entirely to blame?

While observers might be surprised that he harboured despotic tendencies, never had he hid his stripes. This was what made me voted for him in 2014. In his short tenure as a governor of Jakarta (2012–14), he was famous for admonishing sluggish bureaucrats. As a president, Jokowi also has been transparent with his tolerance of undemocratic means to protect democracy, such as disbanding the Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia in 2017 to protect Indonesia from radical Islam. As he was re-elected in spite of his transparency, his undemocratic tactics were validated: he has a democratic mandate to achieve his goals via undemocratic means. This does not acquit him, but it does point to the flaw in the Indonesian society that desires decentralisation but continues to reward a popular leader who centralises. Perhaps this also indicates the weakness of the very concept of democracy, which is unable to prevent the repetition of history, a relapse of the majority to continuously put a despot in office.

Are Indonesians to blame?

Putting the burden on the people assumes that they have choices, and they deliberately choose badly. But the choices are an illusion: they are being asked to choose between people cut from the same cloth: Jokowi or Prabowo, both Islamists, both Nationalist, and both would have had to embrace the system that is flawed.

The interrogation of agency in Indonesia’s politics demonstrates that answering who killed Indonesian democracy is less important than understanding the tragedy itself. This tragedy involves a deterministic trap created by a system that is inherently hostile to accountability; what makes it even sadder is that the elite and the people perpetuate that hostility by their own free will. The essence of the tragedy is thus the circularity of a flawed system and bad actors. The system fosters the worst in people, but everyone’s choice remains: they could plant seeds for reform; instead, they continue to choose expediency at the expense of democracy.

Like McDuff, who eventually kills Macbeth in the final act, if Jokowi chooses not to step down, he will face stern resistance from the Pemuda. But escaping the trap is not a simple matter of balancing or overthrowing a despot. The harder task is to unlearn the mentality of the masses that have been desensitised to the employment of undemocratic means, making them susceptible to electing another despot. This, in the long run, undermines Indonesia’s democracy.

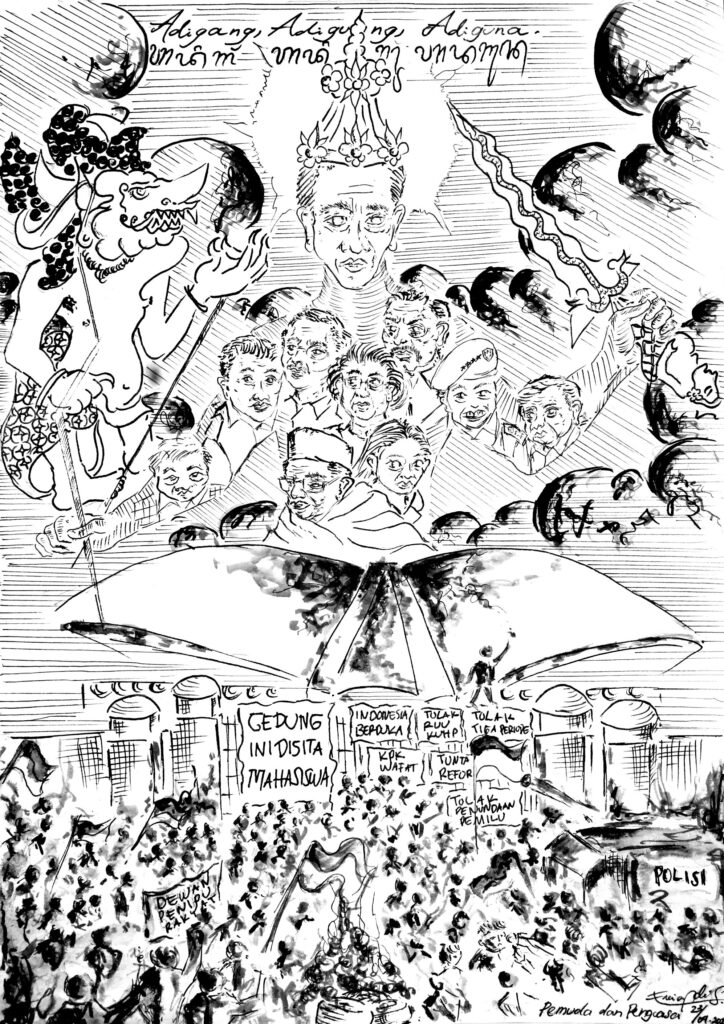

Drawing by the author, courtesy the author.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss