Development of the Greater Sunrise gas field is the key to the economic future of Timor-Leste. But an almost two decade-long maritime territorial dispute with Australia could see ordinary Timorese people pay a high price for policy failure, Rebecca Strating writes.

On 29 August, UN conciliation processes began in The Hague between Timor-Leste and Australia in an effort to resolve the long-running dispute over maritime territory in the Timor Sea.

While Timor-Leste hopes this will solve the impasse, the conciliation process is limited in what it can achieve. A panel of five independent conciliators will offer non-binding recommendations, which are unlikely to substantially change Australia’s approach.

Timor-Leste’s overarching interest is in securing ownership of the lucrative Greater Sunrise gas field and developing an export pipeline to support its oil industrialisation ambitions. The conciliation is part of a broader public diplomacy strategy designed to pressure the Turnbull government to either negotiate permanent maritime boundaries or submit to an international tribunal on boundary delimitation.

In 2002, Australia withdrew from the relevant United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea arbitration instruments, which forced Timor-Leste to negotiate bilaterally within a context of significant power asymmetry.

However, Timor-Leste’s strategy of taking it to The Hague fails to circumvent the key impediments and intractable disagreements preventing it from achieving its Greater Sunrise goals.

The real policy challenge for Timor-Leste is its heightened vulnerability caused by a rapidly declining economic situation.

To put it bluntly, Timor-Leste is running out of time.

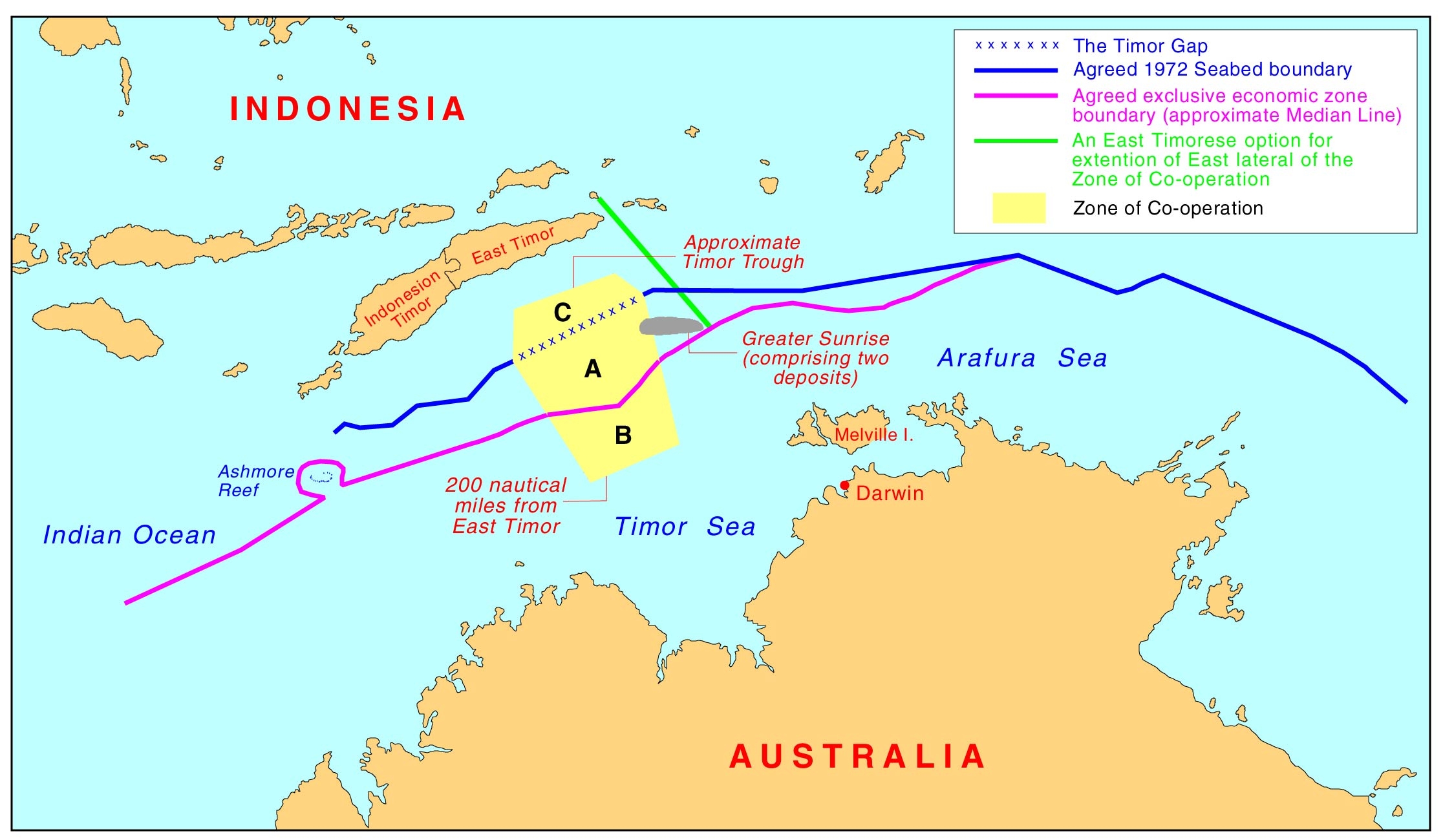

Around 95 per cent of Timor-Leste’s state budget is derived from oil and gas revenues from the Joint Petroleum Development Area (JPDA – see map 1), which constitutes around 80 per cent of Timor-Leste’s entire GDP. Economy monitor La’o Hamutuk estimates that the Bayu-Undan oil field will stop producing in 2022 and the country’s $16 billion sovereign wealth fund could be depleted by 2025.

Without recourse to a third-party arbitrator for the purposes of delimitation, Timor-Leste’s significant oil dependence creates a vulnerability that has been exploited by successive Australian governments. This should not be surprising: it is consistent with Australia’s historically realpolitik approach to the Timor Sea and questions of East Timorese self-determination.

Timor-Leste’s rejuvenated bid for permanent maritime boundaries has been supported by activist-style rhetoric from government leaders that positions maritime boundary delimitation as the ‘final stage’ of Timor-Leste’s achievement of sovereignty. While the Turnbull government has refused to enter discussions about permanent maritime boundaries – supporting instead the current, legally-binding treaties and moratorium on boundary delimitation – many supporters of Timor-Leste’s claims are dissatisfied with these treaty arrangements.

Timor-Leste views the 2006 Treaty of Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea (CMATS) as invalid due to alleged Australian spying during the 2004 negotiations. The spying allegations were not new, but seemingly dug up as a deliberate tactic designed to disentangle Timor-Leste from the CMATS. An International Court of Justice case to determine the validity of the CMATS is currently pending.

If Timor-Leste wins, it will mean going back to square one with Greater Sunrise negotiations. It is difficult to see how this presents a practical, long-term solution for resolving the dispute.

Despite the symbolic rhetoric about boundaries and sovereignty, the real contest around permanent maritime boundaries concerns where those boundaries should be drawn. This relates to Timor-Leste and Australia’s differing interpretation of international law, specifically the guidelines provided by UNCLOS in boundary delimitation.

One misleading claim that recurs in commentary on this issue is that Timor-Leste would own the Timor Sea oil and gas if boundaries were settled according to UNCLOS principles of the median line.

It is true that the median line is supported by contemporary treaty law, state practice and international jurisprudence. However, the crucial line in determining ownership of Greater Sunrise specifically is not the median line, but the eastern lateral boundary.

Establishing a median line would give the JPDA to Timor-Leste, but it already receives a 90 per cent share of those depleting resources. For Timor-Leste to take possession of Greater Sunrise, the eastern lateral boundary that bifurcates it would need to shift substantially to the east.

Problematically for Timor-Leste, this interim eastern lateral boundary was drawn according to principles of ‘simple equidistance’. Timor-Leste would need to prove why the boundary should be shifted east (eg ‘adjusted equidistance’). Timor-Leste’s leaders rely upon the ‘Lowe Opinion’ commissioned by an oil and gas company that was given original explorations rights by the Portuguese Timor administration in the 1970s. Other legal opinions, however, have supported Australia’s ‘simple equidistance’ argument.

International law is not clearly defined: UNCLOS provides little guidance here beyond the requirement of equity in drawing boundaries. Timor-Leste appears confident that it would win in a court of law, but Australia’s intransigence renders this an increasingly moot point. It seems unlikely that this conflict will be resolved in the future without either state compromising their respective claims.

The Timor Sea dispute increasingly resembles a game of brinkmanship, one that may prove disastrous for Timorese statehood. Australia can afford to prolong the dispute, and history tells us that it will continue to protect its national interests. But how will Timor-Leste furnish its state budget if an exploitation plan for Greater Sunrise is not agreed upon by 2025? Even if Timor-Leste could convince Australia to resolve the boundary in the ICJ, a resolution would be years away. Whether the court could even treat this as a bilateral dispute is questionable as Indonesia looms in the background as a potential third claimant.

The activist rhetoric of political leaders has inflamed the nationalist passions of the Timorese community about the Timor Sea, which renders it increasingly unlikely that leaders will be able to compromise without public backlash. Yet the dispute will remain unresolved as long as Timor-Leste continues to pursue its uncompromising and unrealistic foreign policy strategy.

Most troublingly, it will be ordinary Timorese citizens – not Dili elites – who will ultimately bear the cost of policy failure.

Bec Strating is a lecturer in Politics in the Department of Politics and Philosophy at La Trobe University, Melbourne.

This article is a collaboration between New Mandala and Policy Forum — Asia and the Pacific’s leading platform for policy analysis and discussion.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss