In this exhibition review, Paul J Farrelly looks at the evolution of Burmese classical music since the 19th century.

‘Unfaded Splendor: Contemporary Development and Multiple Representations of Myanmar/ Burmese Classical Music’

Hosted by the Academia Sinica Institute of Ethnology

Curated by Tasaw Lü呂心純, Associate Research Fellow, Academia Sinica Institute of Ethnology

The manner in which contemporary Myanmar engages with the wider world is a fascinating topic. These exchanges have occurred over many centuries and in different realms, such as music. ‘Unfaded Splendor’ shows the evolution of Burmese music in the context of global interactions up until the present day.

Dr Tasaw Lü has curated a visual and sonic narrative of the evolution of Burmese classical music since the 19th century. Integral to this are the interactions between Burmese musicians and those from the West and China, the manner in which instruments were innovated, and how music has been (and continues to be) used by elites for political purposes at various times. Beyond providing a thorough account of these historical processes, the exhibition offers an immersive Burmese musical experience. In a sense, the exhibition is an extension of her Chinese-language monograph Unfaded Splendor: Representation and Modernity of the Burmese Classical Music Tradition.

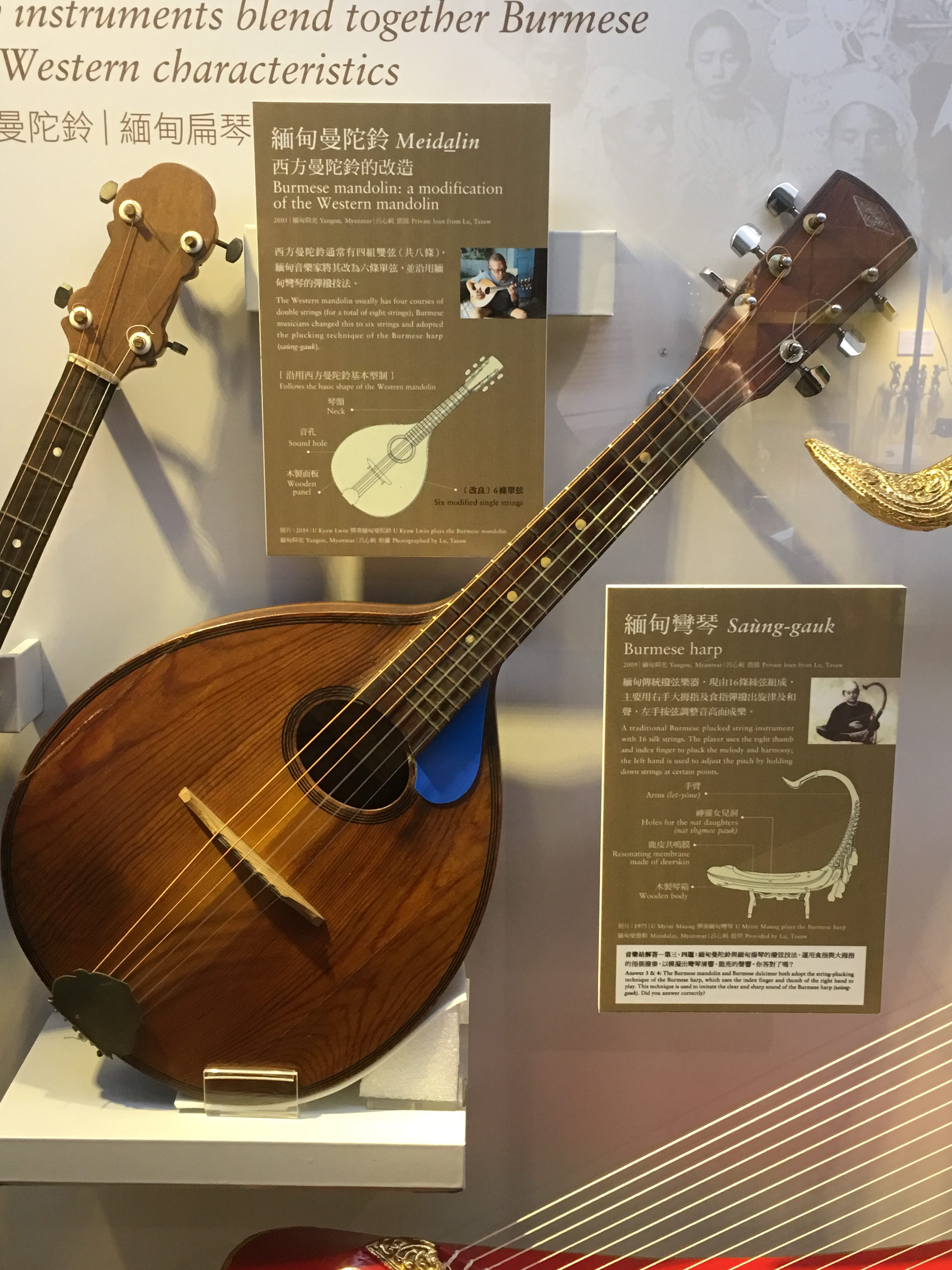

Dr Lü has been building her collection of Burmese instruments since 1998. These comprise the bulk of the exhibition and it is a range rarely seen overseas. There is also a selection of costumes and marionette puppets. The centrepiece of the exhibition is a large percussion ensemble which visitors may get close to and admire. Beyond this impressive instrument, the exhibition includes a number of smaller pieces, including a Burmese mandolin.

Along with instruments such as the violin, dulcimer and piano, the Burmese mandolin was introduced with the commencement of British rule in the late 19th century. Unlike the Western mandolin, which has four sets of two strings, Burmese musicians modified their mandolin to have six strings. This creative adaptation extends to how it is played, with musicians strumming it in a manner similar to the Burmese harp. It was also more physically robust than the harp, making the new instrument easier to carry around.

A field recording of the Burmese mandolin, improvised by U Thein Ggi. Courtesy of Tasaw Lü.

The exhibition allows us to consider the global flows of musical cultures: exchanges between Burma and the West were not always one-directional. The Denishawn Dancers, a California-based modern dance troupe, spent time in Burma during their sixteen month tour of Asia in the 1920s. Their exposure to local performances was eye-opening and provided them with new dance moves and costume ideas. By incorporating these into their repertoire, the Denishawn Dancers also added some American flair, sultrily smiling for the camera in a way that was taboo for the local dancers. While open to accusations of cultural appropriation or orientalism, the Denishawn Dancers offer an intriguing early example of how Burmese performances were represented abroad.

The exhibition also introduces several key figures in contemporary Burmese classical music, such as Kyaw Kyaw Naing (born 1963). At the age of 22 he inherited leadership of Burma’s National Hsaing Orchestra from his father. He continued in this role until 1997 when, after participating in an artist-in-residence program in the USA, he decided to stay there. Working as a sushi chef in New York and sending remittances to his family in Burma, he was not able return home until 2013. Having reconnected with his homeland, Naing now has more opportunities to perform and teach Burmese classical music there and abroad.

Dr Lü has cleverly created an environment where the audience can experience the recent development of Burmese classical music. Certain parts of the exhibition can be interacted with, giving guests the chance to feel the textures of the instruments. Through the variety of exhibits, text, sound and vision, one may gain a sense of the different social roles of music. ‘Unfaded Splendor’ is a thorough and engaging exploration of an important and diverse part of Myanmar culture. It is designed in such a fashion that visitors can appreciate the evolution of music in Burma over the last two centuries. For the convenience of foreign visitors, explanatory notes have been translated into English.

‘Unfaded splendor’ closes on 30 November 2016. A portion of the exhibition will later be displayed at Taipei National University of the Arts 國立臺北藝術大學, which in 2017 will also host Burmese musicians in a series of workshops.

The exhibition is located at the Academia Sinica Institute of Ethnology Museum, 128 Academia Road (sect. 2), Nankang, Taipei, open Monday and Friday from 9:30 to 16:30 (except for public holidays)

For more details, contact [email protected]. The exhibition’s website is here.

Paul J Farrelly is a PhD candidate in the Australian Centre on China in the World at the Australian National University. In 2016 he is in Taiwan as a Research Fellow at the National Central Library and Visiting Fellow at the Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica. He can be found at www.pauljfarrelly.com and is on Twitter @paul_farrelly.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss