‘Gradually raising themselves from a sitting to a kneeling posture, acting in perfect accord in every motion, then rising to their feet, they began a series of figures hardly to be exceeded in grace and difficulty…’

Frank Swettenham, 1878.

Three years after witnessing a performance at the palatial home of Pahang’s Bendahara Tun Ahmad, Frank Swettenham presented his paper A Malay Nautch at a meeting for the Royal Asiatic Society in Singapore in 1878. From the tone and tenor of his occasionally bold observations, Swettenham’s audience were undeniably captivated by this previously undescribed sensual world of dance and music.

At the time, the young unmarried Swettenham who was a good twenty years away from his illustrious title of First British Resident of the Federated Malay States, was evidently more intoxicated by the dancers resplendent in their ornate costumes than with the music. Yet despite the emphasis on eye candy, Swettenham’s lush recount remains the only written record of the great Malay court dance, the joget gamelan, prior to coming under the patronage of the royal court of Terengganu in 1913.

The story of Joget Gamelan is also one of love and marriage. In 1811, Tengku Hussain, the son of Sultan Abdul Rahman of Riau-Lingga married Wan Esah, the sister of Bendahara Ali of Pahang. He brought the Joget Gamelan to Pahang where they became part of the royal household, until it was transferred to the court of Terengganu following the marriage of Tengku Mariam, a Pahang princess, to Tengku Sulaiman of Terengganu in 1913.

Though the Joget Gamelan enjoyed the patronage of the Terengganu palace until almost the second-half of the century, the prestige associated with the tradition was more an extension of the royals’ appreciation of the art form rather than so much a tradition that defined their sovereignty.

The sweeping gestures of the dancers, as Swettenham was informed on that long evening in 1875, were said to symbolically represent the agricultural practices of toiling and tilling the land. They referenced their folkloric roots, most likely derived from the Malay island Sultanate of Riau-Lingga, where the Joget Gamelan originated.

But rather than the Joget Gamelan being used to reinforce the status quo, what we can gauge is the high regard the palace had for their performers—‘we were told with much solemnity, that they were artists of the first order’, says Swettenham, indicating just how deeply they were valued as masters of their craft.

Details regarding how music was used in the court dances in Terengganu would be more fully explored by the great heritage pioneer Mubin Sheppard who, in 1966, located a gamelan instrument set inside the Istana Kolam, Kuala Terengganu. His findings would be a significant turning point in revitalising the tradition which had lost its palace patronage in 1942.

Following the death of Sultan Sulaiman Badrul Alam Shah and Malaysia’s descent into World War Two, including the Malayan Emergency which would officially end in 1960, the Joget Gamelan ceased to be performed. The Terengganu palace never forgot their tradition—if anything it was more of a hiatus during a period of mourning, uncertainty and the need to move forward. But it was a significant enough break for a total of 77 compositions to be reduced to a repertoire of 33.

Awakening the allure

But perhaps more than any other Malay traditional performing arts, the Joget Gamelan of today has suffered from the extremities of sinking to the depths of obscurity, to becoming an overexposed symbol of the nation.

Performed at large-scale extravaganzas, parades, theatres and dinner-dance shows to assert the ‘Truly Asia’ national narrative, the Joget Gamelan in all its spawned variations has quite simply lost its original allure. At the same time, rather paradoxically, one is hard pressed these days to find anyone spontaneously performing even its offshoot, joget modern, which has taken the gamelan entirely out of the equation and replaced it with P Ramlee tunes.

Privileging the visual over the aural, i.e. the dance component taking precedence over the music, could well explain the beginnings of the great divide between ‘joget’ and ‘gamelan’. Today in theatrical showcases, the gamelan music is often prerecorded. Even when a gamelan orchestra is present, it is noticeably ‘absent’, much like in a Western theatrical opera performance where the musicians are haplessly confined to the pit. It would seem that their presence on stage was an inconvenience to the general aesthetics of performance.

And yet the most significant aspect of the Joget Gamelan is that the music and dance were created in tandem, with much of its allure evoked by the music being performed live.

Safeguarding the Joget Gamelan tradition

The Joget Gamelan Sustainability and Cultural Heritage Project, spearheaded by PUSAKA, a not-for-profit organisation dedicated to strengthening the viability of the traditional performing arts, is attempting to revitalise some of the allure lost.

In partnership with Pusat Kreatif Kanak-kanak Tuanku Bainun, supported by Yayasan Hasanah, a foundation of Khazanah Nasional (Malaysia’s sovereign wealth fund–Ed.), this project draws together the successors of the last royal dancers and musicians of the Terengganu court tradition with local school students residing in Kota Terengganu.

Working as advisors on the project are the relatives and former students of the legendary primadonna of the gamelan dance tradition, Mak Yang, one of the last of the court dancers of Terengganu. To date, 32 students (16 girls and 16 boys) from Kuala Terengganu and 20 students (10 girls and 10 boys) from Kuala Lumpur aged 14-16 have been trained in the arts of the tradition.

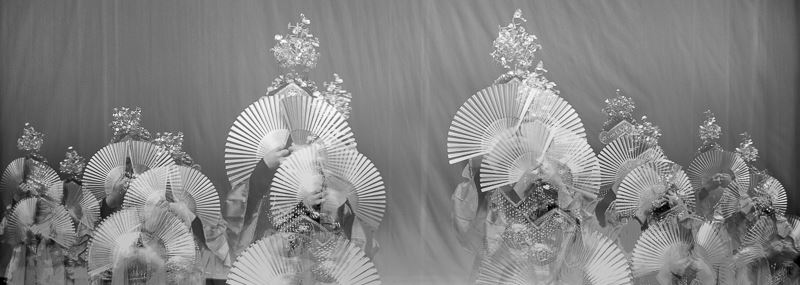

Their training over the past nine months culminated recently in a debut performance ‘Gema Gemalai’ recently at the KuAsh Theatre, Kuala Lumpur, with two items out of the four items the ‘Silat Tari’ and ‘Joget Gamelan Togok’ performed by students from underprivileged backgrounds. In less than a year, the students have become accomplished performers of a handful of numbers that form part of a much larger repertoire.

The biggest thrill for these boys and girls was the chance to perform before members of the Perak royalty, just as they might have done a couple of hundred years ago, bringing this event to a full-circle.

Continued support for the program will ensure their prospects of becoming custodians of the great Malay tradition, while revitalising the original allure of the refined Joget Gamelan tradition. Not only is the public’s appreciation enhanced by these showcases, but also the tradition’s legacy which will ensure its survival for many years to come.

Maybe the allure of the Joget Gamelan which had completely captivated Swettenham is making a return.

……………

Julia Mayer is a Masters of Museum and Heritage Studies student at the Australian National University. She has lived in Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam and South Korea, and has written extensively on traditional arts, performances and cinema in the region. She is also the Asia Correspondent for Metro Magazine Australia.

All photos copyright Cheryl Hoffmann. Cheryl Hoffmann is a freelance photographer based in Southeast Asia.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss