“Fake news” has become a buzzword in the contemporary political lexicon around the world. In Indonesia, there has been significant concern about the so-called rise of berita hoax (“hoax news”) in the aftermath of the 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial election.

As more and more Indonesians turn to social media for their daily news intake, political parties and interest groups have, unsurprisingly, attempted to influence people via these platforms. Like in other countries in the region, much of the everyday discourse on this issue adopts the language of war—social media has been “weaponised” by “online armies” and “cybertroopers”. Indeed, a global study by the Oxford Internet Institute’s researchers has identified a rising tide of “bots” and paid fake social media accounts commissioned to spread disinformation. In Indonesia, “Black campaigns” based on libellous or outright fake material are increasingly generated and spread online, as shown by the recently exposed “hoax news factory” called Saracen.

Southeast Asian cyberspace: politics, censorship, polarisation

The internet is both a factor in, and a victim of, the region’s crisis of democracy.

Cracking down on disinformation “factories” like Saracen is one thing, but not all disinformation spread via social media is done so via paid Facebook advertising or Twitter bots. Much material is shared by ordinary citizens themselves, aided by the increasing popularity of chat apps like WhatsApp and Telegram.

Indeed, a focus on the channels for distributing disinformation leads policymakers away from addressing the more fundamental problems that make Indonesian voters targets for hoax news in the first place: declining trust in democratic leaderships and mainstream media, combined with low levels of digital literacy.

The trust deficit

Trust in professional journalism is quite low in Indonesia. In a 2017 survey on trust in major institutions, the lowest ranked were political parties (45%), the parliament (55%), the courts (65%), and the mass media (67%). Even the notoriously corrupt Indonesian police (70%) ranked higher than the press.

Such results are understandable when we look at the products that many of Indonesia’s most popular news outlets are offering consumers. Indonesians’ most popular source of political news is broadcast television—where the industry-wide problems of oligarchic interests’ influence on content are most obvious. Metro TV (which is owned by Surya Paloh, chairman of the pro-Jokowi NasDem Party) is generally considered to be a mouthpiece for the Jokowi government. Outlets belonging to Jokowi’s rivals have displayed the opposite bias, with news coverage slanted towards criticism of the government.

Mainstream media have themselves not been above broadcasting disinformation. For example, on the night of the closely fought 2014 presidential election, tvOne treated the losing candidate (Prabowo Subianto, whom the network’s owner had supported) as if he had won, and produced fake polls to back its claims. Skewed coverage like this has led to a general belief that all mainstream media are partisan.

tvOne broadcast on presidential election day 2014, showing false projection of Prabowo win. (Photo: Liam Gammon)

In this climate, people turn to alternative sources of information. These sources are mostly online, and mostly within their own social media networks. As a social media campaigner explained to me:

A lot people who are accessing news online are doing so because they are searching for what they feel is the truth, their truth. A lot of the stories being created and distributed online [during the Jakarta election] were of how you should feel.

In this environment, citizens can be compelled by the opinions prevailing in their social media feeds to become divided on sectarian or other identity issues.

Facebook is the central medium for this divisive discourse. Facebook bloggers and social media celebrities, such as Jonru Ginting and Felix Siauw, are a highly innovative new form of campaign communication practice. These figures use social media like a blog, posing as straight talkers who “tell it like it is”. Their social media-centric strategies are perfect for citizens who spend more and more time on their mobile phones scrolling through social media sites. These authors interpret the mainstream news—which they claim is biased—for their fans, claiming often to provide the real truth, the inside story. Cracking down on alternative social media commentators—even if they are guilty of spreading fake news and hate speech—often only fuels the conspiracy theorists’ feeling that this real truth is being silenced.

More broadly, the Facebook commentariat are clearly distinct from the sanitised, bland rhetoric churned out by public relations teams, as was so dominant in the first decade of the 21st Century (think here of Tony Blair in the UK, or SBY’s well-crafted but nondescript media persona). As media scholar Eric Louw put it, this was the era of the “PR-ization of politics”. We have now arguably emerged into the era of a more personalised and informal information society.

Fake news, from friends

Of course, Indonesia’s culture of sharing disinformation did not originate with digital technologies. In 1994 article on the role of rumour during Suharto’s military dictatorship (1965–98), the anthropologist James Siegel wrote that “rumor is subversive in the New Order not when its content is directed against the government, but when the source is believed not to be the government”. Under authoritarian rule, the practice of passing on information, rumours, and gossip became a heightened aspect of being an Indonesian citizen, in order to understand the real story, the extra information. A non-government source, particularly if it is someone you trust, became more believable. As we have heard, in many ways this practice continues in democratic Indonesia, simply moving online.

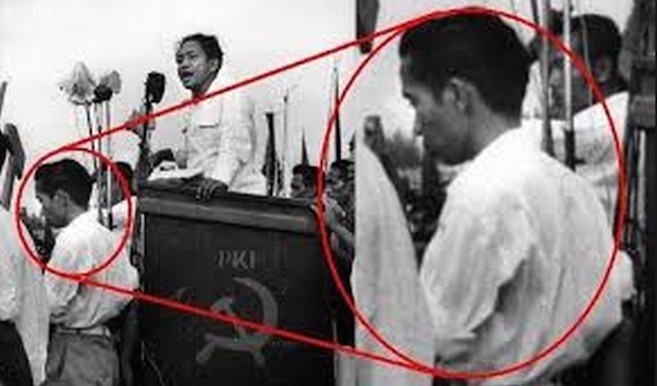

A typical hoax image circulated online in Indonesia, purporting to show a young Jokowi (marked in circle) alongside Indonesian Communist Party leader D.N. Aidit

This lack of trust in official sources is in many ways completely understandable. One recent incident caught my attention as an example of why. In June 2016, the Indonesian media reported on a scandal in which 14 hospitals and 8 clinics were providing counterfeit vaccines, and had allegedly been doing so for up to 13 years. Panic set in among the hundreds of parents affected. As one mother explained, she “didn’t expect much, just information on what to do if her daughter had indeed been given a fake vaccine”.

Faced with this predicament, a group of parents followed what is an increasingly common practice in Indonesia: they formed a WhatsApp group. The intention was to circulate any information related to the scandal, in the hope that their members would be better informed. The hospital, government, and even the mainstream media had ulterior motives, or as one mother stated: “They can say whatever they like because they know their children or grandchildren did not get a fake vaccine.” Understandably, the parents placed more trust in their personal networks, circulated through WhatsApp, than they did in official information sources.

Stuck on the wrong side of the digital divide

Central to this shifting information society are the millions of Indonesians who are accessing the internet for the first time—at all age groups—predominantly through cheap, Chinese-made Android handsets and using the internet via 2G technologies. But because of slow bandwidth and minimal access to decent wifi in these locations, these Indonesians don’t watch videos or google information: they are mostly using 2G to chat with friends on Facebook and WhatsApp. It’s difficult to measure how many people; when answering professional surveys many citizens answer “yes” to having Facebook but “no” to having internet access.

For many Indonesians just getting online, Facebook is the internet, and as Elizabeth Pisani noted during her travels around the archipelago “[m]illions of Indonesians are on $2 a day and are on Facebook”. The hazards associated with the rapid adoption of the internet amid low levels of education have been illustrated in the past year in Myanmar, where Facebook is acknowledged as being a key medium for anti-Muslim hate speech.

The challenges of the Indonesian case generate fewer headlines, but are no less significant. In the next decade, perhaps a hundred million Indonesians will begin to use the internet for the first time in their lives. If current trends continue, they will do so via only a segment of what “the internet” can offer, and will access these sites without any basic knowledge of its biases, harms, and powerful capability to influence. This is already having profound effects on politics, religion, and how citizens access information, but should be addressed immediately.

So what is the outlook for the internet’s role in Indonesian democracy, in a context where rumour and disinformation have long been a staple of everyday political discourse?

Certainly, state responses to the disinformation problem have been inadequate. There is little by way of digital literacy programs in Indonesia. In 2013, the national curriculum controversially removed ICT, replacing it with “Bahasa Indonesia, nationalism and religious studies”. According to recent research on this issue, schools contribute to only 3.68% of “digital literacy activities” in the country. Over 56% of digital literacy activities originated in universities, showing a clear class divide in obtaining digital literacy skills.

What can be done

I have argued here that Indonesia’s information society is shifting rapidly due to the growing prevalence of mobile phone and social media usage, which is concurrent with declining trust in mainstream media. If there is little trust in the democratic institutions that provide society with information, then alternative sources flourish. The rise of “hoax news” is thus a reflection of longer-term failures on the part of these institutions, rather than something that can be fixed easily and immediately by attacking the end product.

Strengthening independent and reliable information sources, rather than the increasing the power of security forces online, is a better solution for what ails Indonesia’s information society. The first step involves improving Indonesia’s mainstream media credibility. This will require more commitment to non-partisan journalism on the part of media proprietors and editors, and commitment from regulators to enforcing existing standards of objectivity. As I’ve previously argued, Indonesia’s long-neglected public broadcasters can and should be given more resources to become sources of credible news.

The second step is to address the challenges of internet access and speeds, which would give news consumers on the wrong side of Indonesia’s “digital divide” options other than Facebook and WhatsApp for their political information.

Lastly and most importantly, digital literacy initiatives in the lead up to the 2019 elections should be of leading importance to the Jokowi government. A top priority is restoring and extending the place of ICT and digital literacy education in the national school curriculum. As cheap smartphones fall into the hands of younger and younger Indonesians, so too must education on how to critically assess online sources of information begin at earlier ages. Young people, equipped with the tools to help themselves, their friends, and relatives tell a hoax when they see one, will be a crucial part of the pushback against online disinformation.

But we are undoubtedly living in a time where people feel their identity groups are being degraded, humiliated, or even under attack—and despite the best efforts of policymakers many of them will find a home in so-called “filter bubbles” or “echo chambers” on social media. Social media discourse thus both changes and reflects contemporary society’s character—and emotional political campaigns encouraging sectarianism and ethno-nationalism are unlikely to dissipate anytime soon.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss