By dismissing the case against Im Chaem, Cambodia’s government has shown that it is willing to draw a line that international justice cannot cross when it comes to making former high-ranking members of the Khmer Rouge accountable for their past crimes. It raises serious questions about future trials, writes Rebecca Gidley.

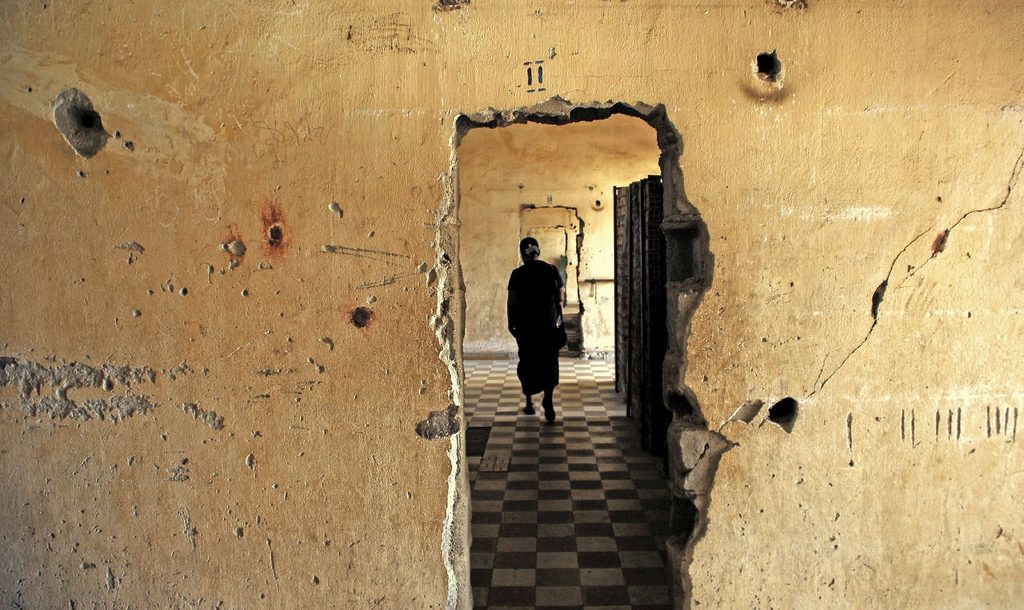

If justice for the Khmer Rouge’s crimes is a competition, then the Cambodian government just won an important victory. Khmer Rouge leaders are being tried by the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), a hybrid domestic-international court with a mix of local and international judges. But the definition of what constitutes a Khmer Rouge leader, given the court is mandated to prosecute “senior leaders of Democratic Kampuchea and those who were most responsible”, has been hotly contested.

So far the ECCC has convicted three people: Kaing Geuk Eav, Nuon Chea, and Khieu Samphan, all of whom have been sentenced to life in prison. The international judges and prosecutor have long favoured the investigation and likely prosecution of four additional suspects across two cases known as Cases 003 and 004. The Cambodian judges, on the other hand, have consistently opposed these. Now, the case against one of these suspects, Im Chaem, has been dismissed by the Co-Investigating Judges.

In some ways this decision is not a surprise; the Cambodian government has strong control of the judiciary and has vociferously opposed these cases. Prime Minister Hun Sen told UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon that these cases “will not be allowed.” Government officials warn that if these cases are pursued they risk the return to civil war which would result in “killing 200,000 to 300,000.” Im Chaem herself, who was accused of homicide and crimes against humanity in connection with her role as Secretary of Preah Net Preah district in the Northwest Zone, has told journalists “I’m happy because I feel protected by the government. Especially Prime Minister Hun Sen is protecting my life.”

The Cambodian government only wants to see the very top leaders of the Khmer Rouge put on trial. To move any further down the chain risks implicating people connected to the ruling party and challenges its reputation as the saviours of the nation, rather than former Khmer Rouge cadres. Accordingly, the Cambodian judges at the ECCC have argued that additional suspects do not fall within the court’s jurisdiction. The Co-Investigating Judges (one Cambodian and one international) have now found this to be the case for Im Chaem. The international Co-Prosecutor, on the other hand, has argued Im Chaem was responsible for purges of Khmer Rouge cadres and their families, and that she oversaw security centres where “thousands of individuals were arbitrarily arrested, detained and executed.”

However, this is not a simple story of the Cambodian government impeding justice. It is questionable if putting a few more elderly leaders on trial is any greater measure of justice for Cambodian victims. And although the international judges at the ECCC have generally supported the advancement of these cases, they have not received international backing to do so. UN responses to government interference in the court’s work have been minimal, and some foreign donors are reluctant to fund Cases 003 and 004.

Now that the decision to dismiss the case has been made, there are limits to how critical advocates for the court can be. In response to the dismissal of the case against Im Chaem, the UN Secretary-General’s Special Expert on the ECCC said that this outcome is “available under the rules” and was not “a waste of funds.” Yuok Chhang, the director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia, said that the court “must follow the rules and the evidence, [even if] it is difficult to take.”

That this dismissal is linked to persistent government interference is a highly likely, although not entirely inevitable, conclusion. However, for advocates to focus on this aspect of the decision risks threatening the legitimacy of the court as a whole, and the cases it has concluded so far. Since the legitimacy of trials such as those at the ECCC is prefaced on their adherence to rules of procedure, the only safe course of action is to also trace this decision to the rules. Stronger rhetoric on the case of Im Chaem is sacrificed to protect the ECCC as a whole.

The dismissal poses plenty of unanswered questions. It can be appealed and theoretically overturned, and full reasoning for the decision has not been released. It is unclear what will happen to the documents and other evidence that have been collected as part of this investigation. And while it sets a precedent for the dismissal of the case against the other three suspects in Cases 003 and 004, full reasoned decisions must still be issued, and the possibility of a different outcome remains.

For now, the Cambodian government has successfully defended the line it will not allow international justice to cross.

Rebecca Gidley is a PhD candidate at the School of Culture, History and Language at the Australian National University. Her thesis examines the creation and operation of the Khmer Rouge tribunal.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss