Editor’s note: This essay introduces a special New Mandala series, “Challenges to Charter Change: Critiques from Legal Experts”, co-edited by Nicole Curato and guest editor, Bryan Dennis Gabito Tiojanco, this essay’s author. Contributors JP. A. Villasor, Dante Gatmaytan, and Björn Dressel examine the process and substance of the proposed change to the Philippine Constitution. This introduction offers a taxonomy of constitution-making which builds upon insights learned from their critiques.

Constitutions live or die by their first few words.

“We, the sovereign Filipino people,” begins the 1987 Philippine Constitution. Whatsoever else comes after this assertion, the most important thing is that enough citizens believe it is true: that it is the People themselves who had promulgated or at least have accepted their own fundamental law. Without widespread faith in its sacred sanction, the Constitution becomes a standard script of political tragedy. Inevitably it would fail to constrain partisan politics and eventually become its plaything.

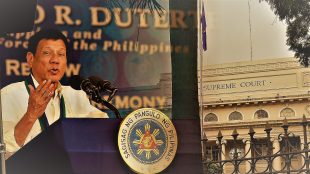

It is for this reason that the revision of the Philippine Constitution which Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte is now pushing for would be the worst kind of charter change.

Bruce Ackerman identifies three kinds of modern constitution-making. The first, revolutionary constitutionalism, happens when a broad coalition of government outsiders successfully mobilises to fundamentally alter the way things are—i.e., the status quo.

The second, insider constitutionalism, happens when government insiders effectively respond to wide-scale popular mobilisation by enacting the publicly-clamoured-for changes to the status quo themselves.

The third, elitist constitutionalism, happens when ascendant elites resort to constitution-making to either entrench a tenuous status quo, or make it even more favourable to them going forward.

Because either the catalyst or engine of the first two kinds of constitution-making is popular mobilisation, we can group them together as people-powered constitution-making. In contrast, little or no popular mobilisation motivates elitist constitutionalism; they are mostly if not entirely elite-driven.

The present push for charter change in the Philippines is a textbook example of elite constitutionalism.

Contributing writers JP Villasor and Dante Gatmaytan argue that, although a shift to federalism was one of Duterte’s campaign promises, there is at present no popular clamour for constitutional change. The administration is both its catalyst and engine. Duterte’s propagandists are resorting to misleading and even lewd advertisements simply to drum up support for the proposal to change the constitution.

Mark Tushnet identifies a paradox of elite-driven constitution-making: it is stable only insofar as it is either unnecessary or ineffective.

The idea that there is such an actual aggregate entity called “the People” which speaks with a singular voice is at best an aspiration. The phrase “We the People” actually means “Plenty enough of Us who have a say in this.” Modern societies are not homogenous, but plural. They house different groups that have divergent ideas about how things should be and what changes to the status quo would be acceptable.

For a constitution of any given society to endure, it must constantly remain acceptable to plenty enough different groups that wield significant power in that society. That is, it must enshrine acceptable norms of their co-existence.

Fundamentally changing the way things are would seriously disadvantage too many powerful groups. Any elite-driven constitutional change would thus be stable only if it either merely ratifies an enduring change in the status quo that has already occurred (and is thus unnecessary), or merely makes cosmetic changes to the status quo (and is thus ineffective). This may explain why, in Villasor’s analysis, the proposed shift to federalism would not substantially alter existing power relations between the national and local governments.

Of course, as Gatmaytan points out, it is possible for an incumbent president to abusively brazen through a charter change which fundamentally changes the status quo. In fact, that is precisely what former Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos did in the 1970s to legalise his dictatorship.

Such brazening through is inherently unstable. The anti-Marcos struggle leading to the dictator’s overthrow in 1986 had dramatised this. Even if all groups were sincere in their commitment to constitutionalism, politics would remain unstable because such an imposed charter would likely bring about nagging disagreement regarding the fundamental norms which would be acceptable to most. Machiavelli had long ago warned that in such circumstances, force and cunning would displace civility and social norms. The brutality of the Marcos years is a cautionary tale of what often happens when this occurs. I share series contributor Björn Dressel’s thesis that process matters as much as content in constitution-making.

Tushnet’s Paradox, therefore, should by itself discourage any further consideration of the proposed federal charter.

Eroding constitutionalism

What makes the proposed charter even worse is that it seeks to replace a constitution which was a product of people-powered constitutional politics. As Dressel’s account of Thailand’s recent political history cautions, such an elite-driven revision of a people-powered constitution could facilitate a liberal democracy’s decay toward illiberal authoritarianism.

We should worry that the impeachment of the Philippines' chief judge signals a new phase in the sidelining of Duterte critics.

Dismantling a liberal constitution, one institution at a time

The “We the People” proclamations of successful people-powered constitutions are thus more accurately assertions of “We are also part of the People.”

These constitutions invariably establish an infrastructure of normal politics which include or consider the constituent groups of this broad coalition in governmental decision-making. Elsewhere I have argued that the present Philippine Constitution is an example of such.

And because these constitutions can credibly boast to be both the product of, and establish a government for, “We the People”, plenty enough citizens would be more willing to comfortably place their hopes and dreams in its principles and institutions. This makes people-powered constitutions more resistant to strongmen, and more effective constraints on partisan politics.

The proposed federal charter, therefore, would only make the country’s presently resilient constitutionalism unstable. This risks turning Philippine politics into a populist playground.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss