Editor’s note: this article appears as part of a series on “Challenges to Charter Change: Critiques from Legal Experts”, co-edited by Nicole Curato and Bryan Dennis Gabito (Bo) Tiojanco. Read contributions from Bo, Dante Gatmaytan, and Björn Dressel

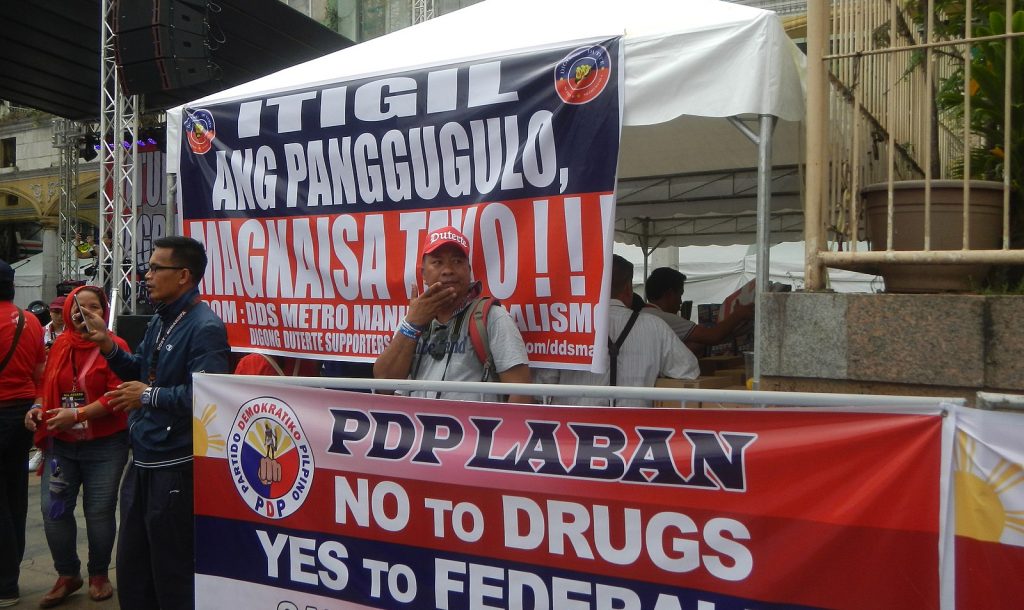

The draft federal constitution which Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte has recently endorsed to Philippine Congress represents a comprehensive and sweeping change from the country’s present Constitution. It recommends a federal-presidential form of government creating eighteen federated regions including federated regions of Muslim Mindanao (Bangsamoro) and the Cordilleras, and redefines, to a considerable extent, the structure of government by adding both an expanded federal bureaucracy and new regional governments.

This essay provides some of my preliminary thoughts on the draft charter.

On federalism

The very notion of federalism rests on the proposition that a group of self-governing states can decide to band together, convene and form a federation of states governed by a common set of rules under a federal constitution. The federal constitution provides the framework that allocates governmental powers between the states or regions, on one hand, and the federal government, on the other.

Herein lies the contradiction of the proposed initiatives to amend the 1987 Philippine Constitution: whereas standard models for federal systems (such as the United States, Canada, Germany, and Australia) had existing, self-sustaining and independent states which could be grouped together as a federated union, the proposed federal government in the Philippines has no separate, existing, self-governing and independent political units to build upon. Genuine federal models work from the state or regional level to the federal level, i.e., from the ground up. The proposed federal charter works in the opposite manner: creating a federal union by dividing up the republic into regions, i.e., from top to bottom.

Instead of developing self-governing units and promulgating state or regional constitutions as the starting point on the road to federalism, the proposed federal charter aims to carve out and divide the Republic of the Philippines, as we know it, into regions without first creating and promulgating regional constitutions. This is a vital point since the 1987 Constitution and the 1991 Local Government Code considers regions as administrative regions for purposes of policy coordination, and not as independent political subdivisions of the state.

While the underlying principle of federalism is to unify distinct states or regions into one nation, the draft charter seems to promote the structural fragmentation of the Philippine Republic as we know it. Moreover, although the draft charter labels the government it proposes as “federal”, it is, in purpose and function, still very much unitary—with provisions on decentralisation of power to local government units similar to the 1991 Local Government Code.

On the constitution of government

The draft charter preserves the bicameral structure of the present Congress. The main amendments include the federalisation of Congress, composed of a Federal Senate and a Federal House of Representatives, the institution of a four-year term for legislators (with one re-election for another four years), and the additional qualification for Federal legislators to be holders of a college degree or its equivalent.

Other major changes include the increase in membership of the Federal House of Representatives to 400, and the election of members of the Federal Senate by Federated Region, where every Federated Region shall be represented by at least two Senators elected by the qualified voters in the Federated Region, provided that each region shall have the same number of senators.

The Federal Senate’s membership was increased to 36, elected by Federated Region under the proposed draft, from the current membership of 24, elected at large.

Under the proposed draft [see PDF here—Ed.], 60% of the members of the Federal House of Representatives shall be elected “by plurality of votes where each single-member legislative electoral district shall have one (1) seat in the House of Representatives. Single-member legislative districts shall be apportioned among the provinces, cities, and the Metropolitan Manila area in accordance with the number of their respective inhabitants on the basis of a uniform and progressive ratio as may be provided by federal law.”

Also, “the remaining forty percent (40%) of the Members of the House of Representatives shall be voted nationwide through a system of proportional representation. Every voter shall vote for a registered political party with a closed list of nominees qualified to be members of the House of Representatives.” Political parties that obtain at least 5% of the valid votes cast under this proportional party representation system shall be considered elected and shall be allocated seats in proportion to the number of votes they received.

The charter proposes that election of the Federal Senate is done by Federated Region, instead of at large, and that the party-list system in the House of Representatives (introduced in the 1987 Constitution) is effectively replaced by the proportional party representation system in the proposed Federal Constitution.

The draft charter essentially preserves the present presidential form of government. The main changes centre on the federalisation of the presidency, the reinstatement of the four-year term presidency (with one re-election for another four years), the additional qualification for the President and Vice President to be holders of a college degree or its equivalent, and the election of the President in tandem with the Vice President.

The draft charter’s proposed changes to the judiciary are the most far-ranging. It proposes to establish four Federal High Courts: the Federal Constitutional Court, the Federal Supreme Court, the Federal Administrative Court, and the Federal Electoral Court.

The Federal Constitutional Court, the Federal Supreme Court, and the Federal Administrative Court shall each be composed of a Chief Justice and eight Associate Justices. The Federal Electoral Court shall be composed of a Chief Justice and fourteen Associate Justices. The Federal High Courts will, in the aggregate, be composed of a total of four Chief Justices and thirty-eight Associate Justices.

The draft charter allots each Federated Region at least one Federal Court of Appeals, at least one Federal District Trial Court in constituent cities and provinces of Federated Regions, and such other lower courts as may be necessary for the effective administration and speedy delivery of justice.

These are significant changes in the judicial hierarchy, where the powers of the present Supreme Court would be divided between the four Federal High Courts. Other Federal Courts are also established, such as the Federal Court of Appeals and the Federal District Trial Court.

Furthermore, the draft charter mandates the Regional Assembly to provide for a Regional Supreme Court, Regional Appellate Court, Regional Trial Courts in component provinces, cities and municipalities and such lower courts and special courts, and define their jurisdiction in accordance with the Constitution.

The proposed changes to the judicial hierarchy threaten the swift dispensation of justice in the Philippines. Under the 1987 Constitution, there are only four levels in the judicial hierarchy (i.e. the Supreme Court, the lower collegiate courts, courts of general jurisdiction, and courts of limited jurisdiction), while under the draft charter, there would be at least six levels in the judiciary, since regional assemblies are empowered to create “such lower courts and special courts” in the form of city and municipal courts.

On the distribution of governmental powers

A new feature of the proposed draft charter involves the distribution of powers of the Federal Government and the Federated Regions.

The Federal Government shall have exclusive power over:

(a) Defence, security of land, sea, and air territory;

(b) Foreign affairs;

(c) International trade;

(d) Customs and tariffs;

(e) Citizenship, immigration and naturalisation;

(f) National socio-economic planning;

(g) Monetary policy and federal fiscal policy, banking, currency;

(h) Competition and competition regulation bodies;

(i) Inter-regional infrastructure and public utilities, including telecommunications

and broadband networks;

(j) Postal service;

(k) Time regulation, standards of weights and measures;

(l) Promotion and protection of human rights;

(m) Basic education;

(n) Science and technology;

(o) Regulation and licensing of professions;

(p) Social security benefits;

(q) Federal crimes and justice system;

(r) Law and order;

(s) Civil, family, property, and commercial laws, except as may be

otherwise provided for in the Constitution;

(t) Prosecution of graft and corruption cases;

(u) Intellectual property; and

(v) Elections.

On the other hand, within the regional territory, the Federated Region shall have exclusive power over the following areas:

(a) Socio-economic development planning;

(b) Creation of sources of revenue;

(c) Financial administration and management;

(d) Tourism, investment, and trade development;

(e) Infrastructure, public utilities and public works;

(f) Economic zones;

(g) Land use and housing;

(h) Justice system;

(i) Local government units;

(j) Business permits and licenses;

(k) Municipal waters;

(l) Indigenous peoples’ rights and welfare;

(m) Culture and language development;

(n) Sports development; and

(o) Parks and recreation.

Essentially, the distribution of powers between the federal and regional governments has already been previously addressed by the 1991 Local Government Code between the national and local governments. The principles of local autonomy, decentralisation of powers, and generation of revenues through the Internal Revenue Allotment, all hallmarks of local government autonomy, have been consistently in practice by the local government units for the last 27 years. The proposal’s much-touted shift to federalism, therefore, would merely give a new name to already existing arrangements which would essentially remain unchanged.

On constitutional commissions

The proposed draft increases the present number of constitutional commissions to six: the Federal Civil Service Commission, the Federal Commission on Elections, the Federal Commission on Audit, the Federal Commission on Human Rights, the Federal Ombudsman Commission, and the Federal Competition Commission. There are presently three constitutional commissions: the Commission on Elections, the Civil Service Commission, and the Commission on Audit. Increasing the number of constitutional commissions will necessarily expand the bureaucracy of the constitutional commissions to at least twice the current number.

On Federated Regions, Autonomous Federated Regions and the establishment of regional governments

The second most substantial proposed change lies in Article XI of the proposed draft charter, entitled “Federated Regions and the Autonomous Federated Regions of Bangsamoro and the Cordilleras.” This Article substantially creates eighteen political units in the form of Federated Regions, including the Autonomous Federated Regions of the Bangsamoro and the Cordilleras.

Each of sixteen Federated Regions will have sixteen Regional Assemblies and Regional Governors, while the Autonomous Federated Regions of the Bangsamoro and the Cordilleras will be governed by their own organic law to be enacted by Congress.

The country’s regions are presently classified as administrative regions, and not as political subdivisions. The distinction here is significant, in the sense that administrative regions do not wield any political power as local government units, but rather as regional aggrupation established to foster and improve better coordination and harmonisation of policies through the regional development councils.

Federated Regions, under the proposed changes, shall be mandated to organise regional governments under a regional governor and deputy governor as part of their regional executive hierarchies. As part of its regional legislative branch, a regional assembly would be established. Each Federated Region would also have its own regional judiciary, namely, the Regional Supreme Court, the Regional Appellate Court and the Regional Trial Courts.

On the constitution of liberty

The Bill of Rights in the proposed draft has 28 provisions divided into three kinds of rights: civil and political rights; economic, social and cultural rights; and environmental and ecological rights. This expands the scope of rights under the 1987 Constitution, which only has 22 provisions.

A glaring addition to the Bill of Rights, under a vastly expanded constitutional right against unreasonable searches and seizure, is the recognition of a “surveillance warrant.” Aside from the two warrants under the 1987 Constitution, namely a search warrant and a warrant of arrest, the draft Federal Constitution includes a warrant to conduct surveillance through technological, electronic, or any other means.

This proposed amendment to include surveillance warrants is a throwback to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) of 1978 in American federal law. FISA establishes procedures for the physical, mechanical, or electronic surveillance and collection of foreign intelligence information between foreign powers and agents of foreign powers suspected of espionage or terrorism. Under US federal law, electronic surveillance is defined as “the nonconsensual acquisition by an electronic, mechanical, or other surveillance device of the contents of any wire or electronic communication, under circumstances in which a party to the communication has a reasonable expectation of privacy.” FISA created the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) to oversee requests for surveillance warrants by federal law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

Unlike FISA, which is narrowly tailored and limited in application to foreign powers and agents of foreign powers involving national security matters, the draft charter does not have any limits to scope and application. All Philippine citizens may be subjects of surveillance warrants even as persons of interest in common crimes.

As to the jurisdiction of courts regarding the issuance of surveillance warrants, the proposed draft is ambiguous about which courts are empowered to do so. It is possible that both federal and state courts would be empowered to issue surveillance warrants requested by federal, regional and local law enforcement authorities. Under FISA, however, it is only the FISC that can issue surveillance warrants requested by federal law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

On the constitution of sovereignty

The draft charter clears an ambiguity of the manner of voting in a constituent assembly. It provides that any amendment to, or revision of, the Constitution may be proposed by the Federal Congress, upon a vote of three-fourths of all its members voting separately.

The provisions on people’s initiative have also been expanded. The draft charter establishes the procedure for proposing changes to the Constitution by way of constitutional initiatives without the need of an enabling statute.

Unlike the 1987 Constitution which merely allows amendments by way of a people’s initiative, the proposed draft Federal Constitution allows both amendments to, and revisions of, the Constitution through a people’s initiative.

On generating public funds to finance the organisation of government

The significant increase in the bureaucracy to finance the Federal Congress and the six Federal Constitutional Commissions require additional allocations in the form of federal taxes. The 2018 General Appropriations Act is PhP3.8 trillion, which can easily double with the increase in the federal bureaucracy and the establishment of regional government units.

The establishment of new regional government units would entail huge expenditures. New taxes would need to be imposed to finance the new regional executive, legislative, and judicial branches of these new political units. Aside from federal and local taxes, regional taxes will have to be created to build the physical infrastructure of these regional government units, finance the administrative operations of each unit, and pay the salaries of elective and appointive officials of the regional governments.

The draft charter requires the imposition of regional taxes to fund the creation of regional governments. The present governmental budget could easily double with the establishment of Regional Government Units. In the 1987 Constitution, there are only two kinds of taxes, i.e., national and local. In the draft charter, three taxes are proposed, i.e., federal, regional and local.

The reorganisation of the judiciary into federal, regional, and local courts is likewise inevitable with the draft charter. This will entail additional funding from federal, regional, and local tax sources.

Federal taxes will also have to be imposed to create four new Federal Supreme Courts: the Federal Constitutional Court, the Federal Supreme Court, the Federal Electoral Court, and the Federal Administrative Court. These will be taxes on top of regional and local taxes, which all citizens are duty-bound to pay. These four Federal Supreme Courts will each promulgate their own Federal Rules of Court to govern pleading, practice, and procedure before the three courts. There will arguably be four versions of the Federal Rules of Court for the proposed Federal Constitutional Court, Federal Supreme Court, Federal Electoral Court and Federal Administrative Court, especially dealing with issues of jurisdiction and venue.

Furthermore, the present allocation on the Judiciary Development Fund, the Special Allowance for the Judiciary, and 0.97% of the General Appropriations Act will be divided in the federal and regional hierarchy of courts.

On the transitory provisions

The timetable set for the transition into the new Federal Constitution is on June 30, 2022. With the sweeping changes proposed in the draft charter, a three-year transition period would be insufficient considering the physical infrastructure for new regional government units is still not in place, and the administrative hierarchy of the regional governments has not been duly organised. In addition, the federal and regional judiciaries have no operating rules of court.

A constitutional postscript

In a hearing of the Senate Committee on Constitutional Amendments during the first quarter of 2018, the noted constitutional law scholar Justice Vicente V. Mendoza said that “what we need is a constitutional moment when people’s minds would be focused on higher things than petty politics to frame a Constitution that we hope will endure.”

It seems that the present time is not that constitutional moment.

A year after referendum, only bad news about Thailand’s constitution

The new constitution leaves booby traps for any incoming civilian government.

As Filipinos continue searching for that constitutional moment, amendments to the 1991 Local Government Code may suffice at present to accelerate the decentralisation of power from the unitary government to the local government units.

Given that political dynasties still abound, it would be more prudent not to pursue charter change in the direction of federalism, where such substantial changes will not redound to the benefit of the nation and the Filipino people.

It would be best to continue studying the federalism proposals and its refinements more carefully, weighing both the benefits and costs of each article, especially on the matter of how these proposals will be financed, i.e., imposing additional tax burdens on the people. More than a formal shift in the system of governance, what is essential is the creation of self-sufficient political units at the local government level.

To achieve a genuine path towards national unity, one must view federalism as, in the words of former Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, “more than a form of government. It’s also a system of values that allows different people in diverse communities to live and work together for the good of all.”

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss