Shortly before Malaysia’s general elections in 2008, I sat on a cool floor with blank placards and marker pens, beneath a whirring ceiling fan in a bungalow house in Kuala Lumpur. I sat there with friends, some younger, some older than my 31 year old self, thinking of slogans for our campaign to educate voters about the representation of women in Parliament and the hurdles that women face in having their voices heard and issues addressed.

The Women’s Candidacy Initiative (WCI) that we were a part of sought to draw attention to the reasons that have led to the ongoing underrepresentation of women in Malaysia’s political system. It did this by publically confronting candidates from the ruling coalition and opposition parties in equal measure and asking them about their commitment to women’s rights, and their dedication to addressing women’s issues if elected.

As we all sat on that floor surrounded by materials bought from a nearby stationery shop, I experienced a moment of sadness and smallness when I thought of the vast resources and professional advertisements being deployed by the Barisan Nasional (BN), Malaysia’s ruling coalition. But moments later I was invigorated with pride and admiration for my colleagues. I realised that what WCI was doing was challenging notions about who could and ought to participate in Malaysia’s democratic processes. WCI was creating a space within which young women in particular could engage with the processes of democracy. By drawing on the creativity and vitality of younger activists, WCI formulated a youthful and media-savvy campaign and got its message out through diverse media, including Al Jazeera and the front pages of national publications.

The particular energy that these young people brought to our campaign is worth drawing attention to. Malaysians, and especially young Malaysians, have often been characterised as being averse to political activism. But the work of scholars like Meredith Weiss has persuasively demonstrated that Malaysia has a rich history of student activism, one which has been actively suppressed and obscured such that many young people today have little idea of it. In this context, work such as Weiss’s book, activist Fahmi Reza’s documentary Sepuluh Tahun Sebelum Merdeka, and discussions such as this on New Mandala, have a potentially important role in reconnecting people with lost histories and stories.

The 2012 Bersih protests in Kuala Lumpur (Photo via Sham Hardy on Flickr, Creative Commons)

What makes the political role of these young people distinctive, says Weiss, is that they tend to differ from other activists in terms of the their collective identity, the moral value they place on that identity, and the “breadth of issues they may champion, including matters with no apparent connection to students’ own interests and positions”. My own experience with activists in Malaysia largely bears this observation out; I have used Nick Crossley’s concept of a “radical habitus” to describe the disposition of many long term or “career” activists—many of whom cut their teeth during their university years—for “contestation and a willingness to explore unfamiliar forms’ to pursue their goals”.

An example that I have written about is that of David Teoh, who was a key figure in Global Bersih, an international movement that seeks to support the work and demonstrations of Bersih, a civil society coalition that seeks reforms to Malaysia’s electoral systems and practices. Shortly after completing his university studies in Melbourne, Teoh became involved, more by accident than by design, in facilitating political speakers from Malaysia. During the 2011 and 2012 Bersih rallies in Kuala Lumpur, he found himself using social media to coordinate rallies in dozens of cities around the world that coincided with, and were supportive of, the momentous Bersih demonstrations in Malaysia.

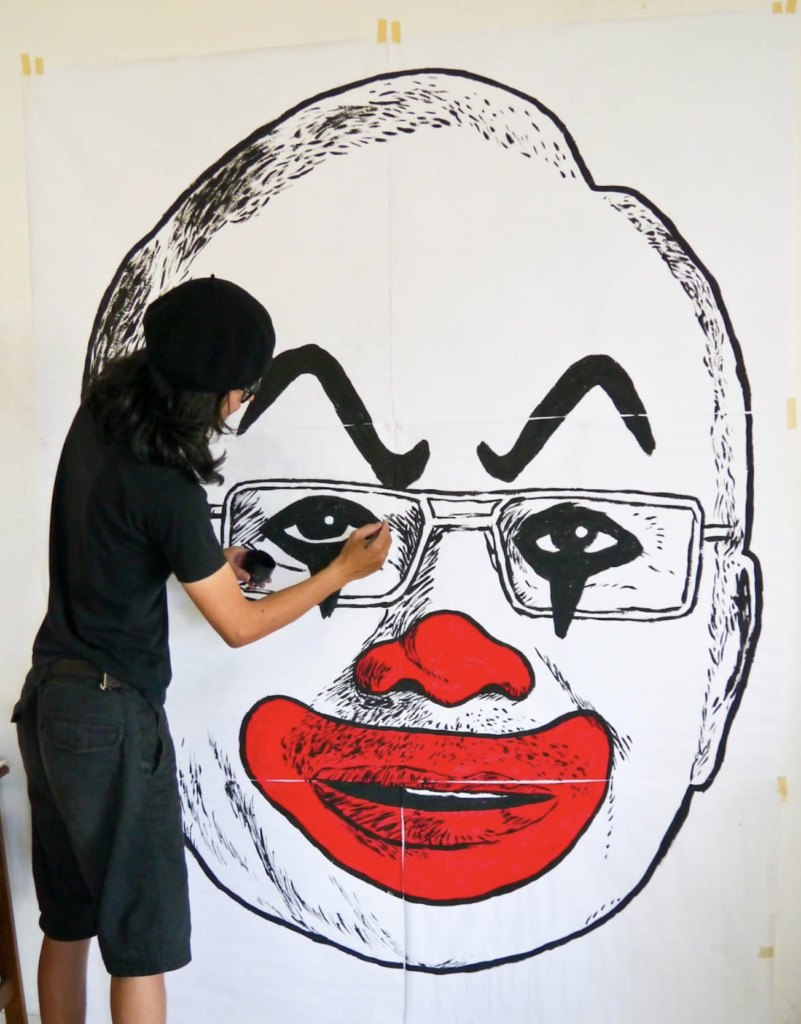

Alongside this organisational improvisation, the creativity of young activists has loomed large. One symbol seen at recent Bersih demonstrations that has become well-known throughout Malaysia is that created and propagated by the young artist-activist Fahmi Reza. The image is of Prime Minister Najib portrayed as a clown, with text beneath stating “Kita semua penghasut” (We are all seditious). This image, which has now received global attention, was developed following allegations of the prime minister’s role in the 1Malaysia Development Berhad scandal. But so cutting has been the impact of the critique that this image undertakes, that Fahmi has himself been charged with sedition.

Fahmi Reza with his now-iconic image of Najib (photo via Fahmi Reza on Twitter)

At first glance, such risks and sacrifice may seem futile. As a BBC journalist observes while interviewing Fahmi in the aftermath of the Bersih rally in Kuala Lumpur in 2016, Najib “is still in power”. But in response to the interviewer’s doubts, Fahmi affirms that protests are successful. “One of the success[es] of the protest,” he says, “is to create this culture of protest in this country. Look where we are today, hundreds of thousands of people are down on the streets protesting, and they are protesting without fear.”

A young person’s game?

Two things come through for me in this remark of Fahmi’s about the developing “culture of protest”. First relates to Weiss’s comments about activism being stymied by its histories being obscured. The now obvious presence of regular protests in Malaysia has rewritten the narrative of Malaysia as a place of popular acquiescence to government threats and directives. The second is that some of the ethos of the “radical habitus” of more seasoned activists may be rubbing off more generally on the citizenry of Malaysia which is, as Fahmi observes, increasingly comfortable with protesting, and is doing so with much less fear. If this trend continues, it has to be regarded as a major success for Malaysian civil society.

But it is not just seasoned activists who are attempting to inspire and motivate the younger generation. The influence also works in the other direction.

A senior women’s rights activists remarked, during an interview with me in 2016, that younger people sometimes persuade her to join or help them in entering into dialogue with the government on a particular issue. When this happens, she recollects the countless fruitless attempts she has been a part of over the years and said, “Ah…but I’ve been there, done that. And then they will [say] ‘No, we have to, we have to.’” At which point, she said, she sometimes relents to their insistence and enthusiasm.

While enthusiasm, idealism and youth are often thought to be synonymous, it is by no means necessarily the case. If we consider the vast array of highly accessible distractions in the form of mobile phone apps, or season after season of highly addictive television series, or the pleasures of consumerism that adverts constantly bombard people of all ages with, political disengagement is all too easy and attractive. This is especially so when young people are dissuaded so actively from any critical activity.

But the realities of the world always break through distractions—such as when people’s economic position means they struggle to afford items they desire or need, when the future offers no realistic promise of improvement, and when the seemingly ill-gotten wealth of the country’s elites is so evident. These realities have been among the factors that prompted the massive protest rallies in Malaysia and which, note James Chin and Wong Chin Huat, have “energized urban young people” who have access to the online media that are “unafraid to discuss sensitive subjects such as high-level corruption, abuses of power, ethnic discrimination, police brutality, religious controversies, and racist remarks by UMNO politicians”.

When voting isn’t enough

The threat that the overt expression of popular discontent poses to ruling parties is considerable, and according to William Case, necessary in the case of Southeast Asia’s semi-democratic or “hybrid” regimes. Although “voting in hybrid regimes is not inconsequential for bringing about change, it is neither a necessary nor a sufficient factor in the Southeast Asian setting”. In the wake of the Asian Financial Crisis, Southeast Asian governments were challenged by failing prosperity and rising popular discontent. The upshot of this discontent was that some countries such as Myanmar became more authoritarian, whereas others, such as Indonesia, moved towards greater democratisation.

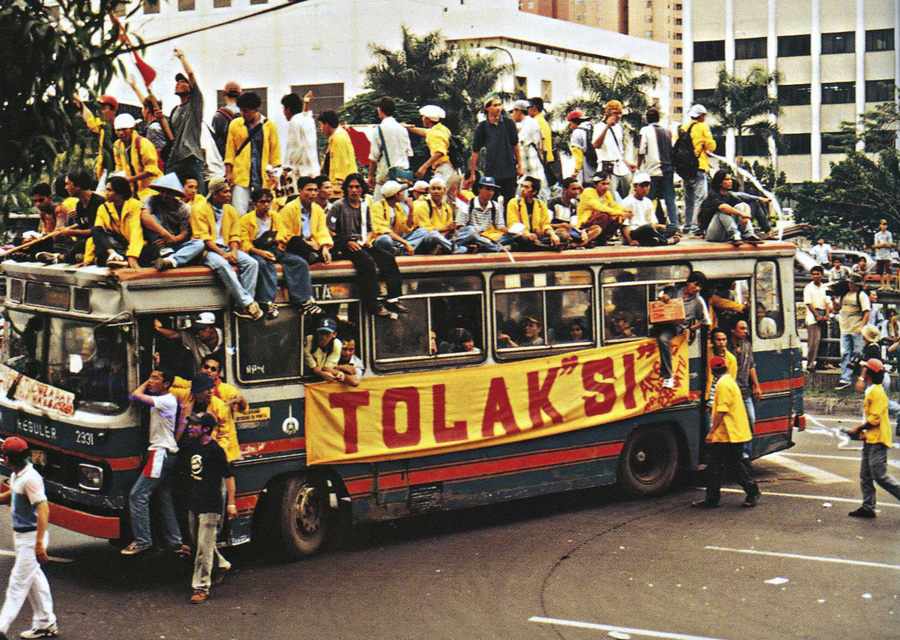

University of Indonesia students protesting against the Soeharto regime, 1998. (Wikimedia Commons)

In the same period, according to Case, others countries, such as Malaysia, were able to ride the rough times through “artful manipulations”, including curbing civil liberties. Although suffering setbacks in the 1999 elections, the Barisan Nasional retained power and later re-cemented its dominance in 2004 with considerable electoral success after the country’s economy recovered. Thus, “while transitions to democracy have surely taken place in the [Southeast Asian] region,” writes Case, “they have been driven not by voters, but more forcibly by protestors”. And it is in this respect that the Barisan Nasional has much to be concerned about in Bersih, which has mustered regular and massive street demonstrations and put paid to the image of Malaysians as docile citizens.

In the face of this, the Malaysian government has been far from idle and has sought to quell the expressions of discontent and protest. The success of the repression that has been unfolding since the revelations about 1Malaysia Development Berhad has led some to observe that in its hope for political change, “Malaysia is waiting for foreign action”.

Putting the desirability of “foreign action” aside, what such sentiments reflect is the seeming lack of options that Malaysians have for bringing about political change or registering their voices. Engaging with political parties would appear to many young Malaysians as a highly undesirable avenue for a raft of reasons. The biased nature of the electoral process has been laid bare, not least by Bersih; political parties all have entrenched power structures, networks and dynasties; and for most young people there are often more immediate concerns about making a living. Against this, the options for engagement in the civil society sphere would seem to offer greater accessibility, more immediacy in terms of efforts bearing fruits, and potentially way more fun—so long as one is not arrested.

And such civil society efforts need not be thought of as separate from party political engagement. It was just this pragmatic engagement that those involved with the Women’s Candidacy Initiative have recognised. They took advantage of whatever opportunities and openings presented themselves. They understood the interconnectedness of the issues at play and the close relationship between what happens in the party-political sphere and the rest of Malaysian society. They also understood the importance of involving young people who not only could communicate effectively with their peers, but who would be able to take over the mantle in the years to come.

“The ideas lying around”

Although I could point towards WCI’s successes in educating both some voters and MPs with respect to issues facing women, and attention given to women’s issues in the media, the importance of civil society ventures—even small ones— must also be seen in terms of its potentialities should opportunities present themselves. In his book How Change Happens, Duncan Green describes the importance of having pre-existing networks, organisations and ideas ready, irrespective of the seeming likelihood of their coming into play.

To illustrate, Green notes that when the 2013 Rana Plaza disaster in Bangladesh occurred, an “Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh” soon came into effect. This accord, however, happened as it did because of the substantial work already done in developing policy, networks, and trust with key actors. Although far from being a subscriber to Milton Friedman’s economic policies, Green cites Friedman, who argued that when a crisis occurs, the actions that will follow will “depend on the ideas that are lying around”, and that what is needed is “to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the political impossible becomes politically inevitable”.

Thus a vibrant, pro-social, inclusive, creative, and hopeful civil society is needed in Malaysia and Southeast Asia more generally—indeed, globally—for when crises emerge, as they undoubtedly will. How countries and societies will navigate their way through those moments will depend on the networks, values, and ideas that are taken into them. In this, young people have been, continue to be, and need to be key in articulating and communicating that which matters, and that which is right.

• • • • • • • •

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss