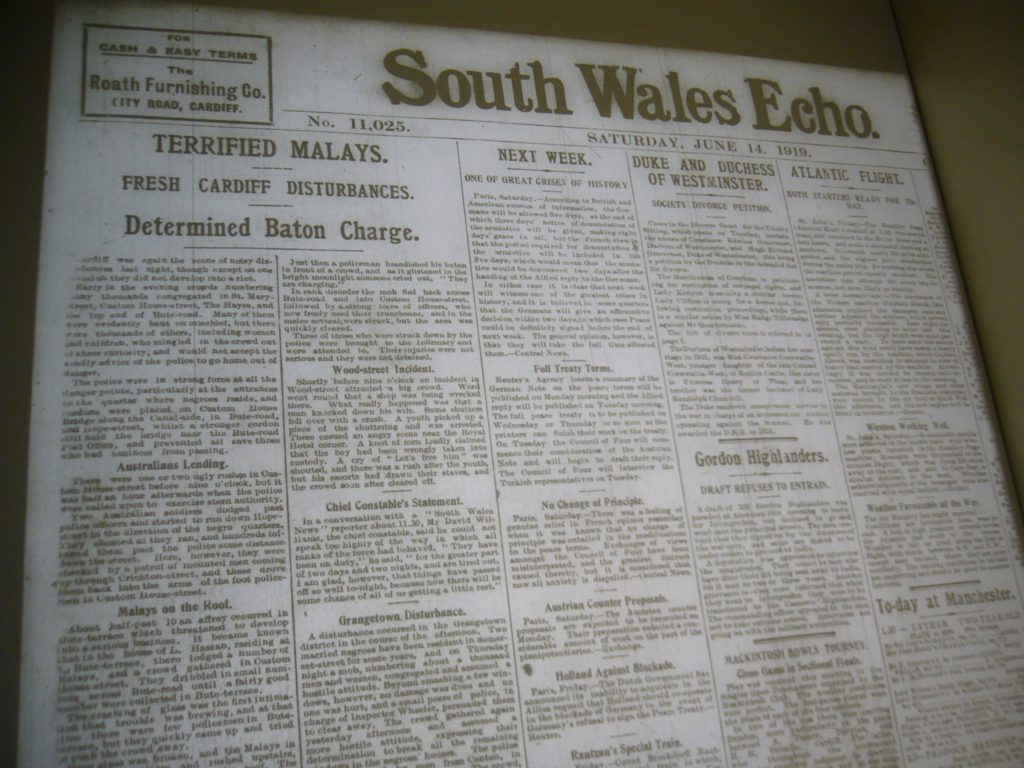

This year marks a significant anniversary of two episodes of racialised urban violence involving Malays in very different ways. In contrast to the infamous 13 May events in Kuala Lumpur fifty years ago, few Malaysians have ever heard about Malay entanglement in racial disturbances in the British port city of Cardiff in 1919. Yet on 14 June of that year, the front page of the South Wales Echo newspaper read: “Terrified Malays”. It reported that during the preceding evening a group of Malay men had been forced to climb onto the roof of their lodging house to escape an angry white mob.

The centenary of the Cardiff riots is an opportune moment to recount the historical context in which they occurred, and to piece together fragments of information about how Malays came to be embroiled in them. In this article, I reflect on Cardiff 1919 and its aftermath in comparative relation to Malaysia’s most deadly riots in 1969. While different in magnitude, and set against very different backdrops fifty years apart, the two sets of events had some common political economic outcomes. In addition, the Malay presence in Cardiff during and beyond 1919 helps to recall cosmopolitan lives that contrast sharply with how 13 May 1969 is conventionally remembered.

Cardiff and the riots of 1919

The four days of riots in Cardiff on 11–14 June 1919 began with a confrontation between a white crowd and a group of “coloured” men. White mobs subsequently attacked the dockside Butetown area where the city’s Black and Asian populations were concentrated. On the evening of Friday 13 June, a crowd gathered outside 8 Bute Terrace and, according to the South Wales Echo, “the crashing of glass was the first intimation that trouble was brewing”. The report continued:

More glass was broken, and the Malays in the house took alarm and rushed upstairs, then up to the attic and on to the roof. The crowd, which by this time had swelled considerably, espied their dark sinewy bodies against the skyline, and a hoarse cry of anger was followed by a volley of stones aimed at the Malays as they clambered through the skylight of the house and dragged themselves on their hands and knees over the top of the roof to seek shelter on the other side.

A “determined baton charge” by the police dispersed the mob and saved the Malays from more serious assault. On the day before the “Malays on the roof” incident, however, an Arab sailor had not been so fortunate. Mahomed Abdullah was killed when the house where he was staying was attacked. Mahomed was one of three men who died in the Cardiff riots. The fact that no Malays were added to the death toll on 13 June was a sign that police and troops had begun to regain control. Nonetheless, the following day, a Malay man was assaulted and had to be taken into protective custody.

LOCAL NEWSPAPER REPORTS ON CARDIFF RIOTS, 14 JUNE 1919 (PHOTO: AUTHOR)

Explanations for Cardiff 1919 have largely focused on the intertwining of racist nationalism and economic dissatisfaction. The First World War (1914–18) intensified competition over seafaring work and wages that had fuelled sporadic conflict between white British sailors and sailors of other ethnicities in previous decades. Wartime exigencies led to an expansion of seafaring employment opportunities available to Black, Arab and Asian sailors in Cardiff. The employment situation in the merchant shipping industry worsened after the war, and white Britons vented their economic frustrations on minority ethnic groups whose numbers had swelled in and beyond Butetown.

Many of the non-white residents of Cardiff and other British port cities in 1919 were (colonial) British subjects. Some had even served in the British armed forces during the war. The fact that they were targeted was a sign of nationalistic association of British identity and entitlement with whiteness. Imperial discourse and practice had also ingrained popular imaginings of racial hierarchy. It is revealing that the confrontational trigger for the Cardiff riots was a group of non-white men returning to the city after an excursion with their white wives: economic frustrations and material jealousy were mixed with sexual tensions and racist fears of miscegenation.

Neither intensified employment competition nor racial scapegoating in 1919 were confined to Cardiff. Indeed, another explanation for the violence in that port city was the demonstration effect of events elsewhere. Severe race riots had broken out in Liverpool on 6 June and were widely reported in the press in South Wales in the days leading up to the outbreak of violence in Cardiff. The events in Cardiff were, in turn, followed by riots in the nearby coal-exporting port of Barry.

Between January 1919, when the first racialised collective violence of the year took place in Glasgow, and August, riots occurred in nine ports across the British Isles. The effects of those riots also rippled out to wider post-war maritime worlds, including on the other side of the Atlantic. The historian Jacqueline Jenkinson has noted widespread disorder and violence in the Caribbean following the return of demobilised Black troops and sailors repatriated from Cardiff and other British ports in the wake of the riots.

Malays in Cardiff and a world of ports

It was through seafaring labour that Malay men came to be caught up in the racialised antagonisms of 1919. During the nineteenth century, Malays were among the lascars (Indian Ocean sailors) who became the mainstay of British-registered ships bound for Europe. In Liverpool, for example, the seafaring “Malay” appears in literary and missionary-related sources from the mid nineteenth century. Cardiff’s subsequent emergence as the world’s leading coal-exporting port meant that it too attracted Malays and seafarers from many other parts of the globe.

CARDIFF DOCKS CIRCA 1910 (PHOTO: WWW.OLDUKPHOTOS.COM)

Although the number of seafarers passing through the port is impossible to calculate, Cardiff’s “permanently settled coloured population” was estimated at around seven hundred in 1914. By the end of the war, that figure had at least doubled, possibly tripled. Working back from enumeration of “coloured alien seamen” as recorded by the Cardiff City Policein subsequent decades, the largest proportions would have been “Arab” (mostly Yemenis), “Africans”, “West Indians” and “Somalis”. It is likely that the population of Cardiff-based Malay seafarers remained fewer than a hundred in 1919, almost all of whom would have lived or lodged in Butetown.

Surviving records do not enable identification of the Malays who were rescued from the white mob in Bute Terrace on the evening of 13 June. However, one Malay seaman who was working out of Cardiff during the First World War was Cambon bin Brahim. Born in Pernu, Malacca, in 1894, in October 1917 Cambon was employed as a sailor on a British merchant ship, the Gefion. During a voyage taking coal to Rouen, France, on 25 October, the Gefion was torpedoed and sunk by a German submarine.

Cambon survived and went on to start a family in Butetown in the interwar period. According to two of his children whom I interviewed in Cardiff in 2008, Cambon continued to work at sea until his death in 1948. Having survived work in the merchant marine during two world wars, as well as the riots of 1919, Cambon died in the Seaman’s Hospital in Cardiff after consuming contaminated water on a seafaring voyage to West Africa.

Cambon bin Brahim’s Cardiff-born children inherited no clear social memory of the events of 1919 despite having grown up in Butetown. What they did recall in the interview was what they termed the “cosmopolitan” composition and tight-knit social bonds of their dockside part of the city. The strong local senses of solidarity and community remembered by Osman John Brahim and Marcia Brahim Barry were at least partly a socio-spatial effect of the events of 1919. In the wake of the riots, non-white people became even more concentrated in—or confined to—Butetown, which was increasingly referred to by the derogatory term “Nigger Town”.

The varied ethnic minorities in Cardiff docks were compelled to support one another in the face of both everyday white hostility in other parts of the city, and a government that viewed their presence as a problem to be resolved through repatriation. State intervention some half a century after the riots of 1919 is also blamed by former residents of Butetown for destroying the area’s cosmopolitan sociality: during the late 1960s, the Butetown area was subject to large-scale urban redevelopment and most of its diverse inhabitants were forced to disperse to other parts of the city.

OSMAN JOHN BRAHIM (R) AT THE DOCKS IN THE 1950s. (PHOTO: SUPPLIED)

From Cardiff to Kuala Lumpur

The dismantling of multiethnic Butetown circa 1969 occurred during the same historical period as the 13 May events that spelled the end of Malaysia’s multiethnic Alliance government. While that concurrence is merely coincidental, I have been struck by some similarities between the 1919 riots in Cardiff and their legacies, on the one hand, and the events of May 1969 in Kuala Lumpur, on the other. Above all, while both sets of events have often been narrated as race riots, neither is reducible to issues of racial intolerance.

The violence in both Cardiff in 1919 and Kuala Lumpur in 1969 took place in contexts of frustrated economic aspirations. In Britain after the First World War, the dockside spaces occupied by minority ethnic groups bore the brunt of majority population grievances over housing as well as job shortages. The riots in Kuala Lumpur in 1969 may similarly be understood at least partly in terms of majority ethnic group anger at perceived inequity in the distribution of national wealth and economic opportunity.

Unlike Cardiff 1919, however, the 1969 violence in Malaysia was set against a backdrop of racial politics. In contrast to both the demographic size and electoral weight of ethnic Chinese in Malaysia in 1969, the numbers of Malay and other non-white residents of dockside parts of British port cities after the First World War were minuscule at the national scale. In addition, while the press, unions and even politicians were far from neutral onlookers in Britain in 1919, there was no equivalent in that context to either the electoral provocation or political orchestration that are central to competing explanations of 13 May 1969 in Malaysia.

There are nonetheless important commonalities in the political effects of the two sets of events. May 1969 was unequivocally a turning point for the political assertion of ketuanan Melayu (Malay supremacy) and the encoding of Bumiputera-first economic policy in Malaysia. Racialised “mob” violence in Cardiff and other British ports in 1919, meanwhile, served to strengthen the position of the (white) national “core” population in the maritime labour market. In addition to compelling British government acceleration and expansion of efforts to repatriate “alien” seamen, unions pressed the shipping industry to prioritise the employment of white Britons—a form of early twentieth-century Bumiputeraism in the metropole.

BUTETOWN IN 1958 (PHOTO: WALESONLINE.CO.UK)

Remembering cosmopolitan geographies and other Malays

Any robust comparison of the political outcomes of racial violence in Cardiff 1919 and Kuala Lumpur 1969 would clearly have to probe much more deeply than the general contextual commonalities and differences that I have selected. Nonetheless, considering the two sets of events together brings into view alternative ways of seeing and remembering across history and geographic location.

Two distinct geographies of Malay cosmopolitanism can be discerned from considering Kuala Lumpur 1969 in relation to Cardiff 1919 and its aftermath. One concerns local-scale transethnic social relations of the kind that were recalled by Cambon bin Brahim’s son and daughter. Another has to do with the long distance seafaring travels undertaken by Malay men, and the cultural versatility that they demonstrated living in Cardiff and other Atlantic port cities.

Transethnic solidarities in Butetown were partly a product of white British hostility to non-white residents and sojourners, including Malays. But that area of Cardiff was also home to many white Britons. Osman John Brahim’s wife, for example, was from a white family who lived in Butetown in the interwar period. Butetown, in other words, was a space of cosmopolitan interactions that exceeded shared experiences of marginality or persecution among members of minority ethnic groups.

Just as it is important to recall ethnic majority–minority solidarities in Cardiff during and after 1919, May 1969 in Malaysia was a moment of many—mostly unrecorded—local episodes of avoiding conflict. The documentary record has understandably focused on sites of interracial violence and destruction that have come to stand for “Kuala Lumpur” and even “Malaysia” as a whole during the period concerned. The recent fiftieth anniversary included efforts to recall and map key sites—Malaysiakini generated an online cartographic timeline of events in and around Kuala Lumpur, and other commentators proposed memorialisation of victims’ burial grounds. But there is surely also value in recalling that local lives which included transethnic neighbourliness and friendship, acts of kindness and protection were far from extraordinary in Kuala Lumpur and across West Malaysia—before, during and after May 1969.

Recalling mundane transethnic geographies of getting along does not mean denying wider historical enmities or turning a blind eye to the violence that officially claimed 196 lives in 1969. It is possible that further excavation of what happened, where—and why—may be therapeutic both for individual Malaysians and at the level of wider society and politics. But more “positive” memories of transethnic social interaction may also be powerful resources for collective efforts to “find a way to heal and move forward”.

The second geography of cosmopolitanism that I wish to recall from Cardiff 1919 concerns the itineraries that took Malay men such as Cambon bin Brahim to Cardiff and other Atlantic port cities in the early decades of the twentieth century. In prosaic economic terms, these were merely a by-product seafaring employment opportunities in British colonial Southeast Asia. Yet we also know from major contributions to Malaysian studies that there are much more expansive cultural histories of mobility among Malay people (or of people who came to be classified as such).

From the end of the nineteenth century, as the late Joel S. Kahn put it, “ordinary Malays” inhabited a world of cosmopolitan mobility rather than territorial fixity. Kahn focused on intraregional Malay mobilities such that transoceanic seafarers who ended up in Cardiff might be considered unusual in their spatial reach. In terms of their openness to the world, to difference, and to others, however, the lives of men such as Cambon bin Brahim were aligned with the cosmopolitan Malayness that Joel Kahn’s research recuperated.

A Changing Malaysia?

A new series of perspectives on the “Malaysia Baharu” from Malaysian scholars, activists, and policymakers.

In this regard, I suggest, the Cardiff of 1919 is an unexpected resource. Recounting how “terrified Malays” became entangled in mob violence in Cardiff in June 1919 is a reminder that racist nationalism and anti-immigrant boundaries are not new to the twenty-first century. But the centenary of the British port riots is also an occasion for remembering hopeful, cosmopolitan geographies—both more localised than conventional city- or national-scale narratives, and potentially global in scope, through Malay migrations that exceed national and regional frames.

Recognition of such geographies is clearly no substitute for demands in Malaysia today to delve more deeply and critically into the events in Kuala Lumpur on 13 May 1969 and their political underpinnings. My documentation of the little-known connections of ordinary Malays to Cardiff 1919 may, however, help us see an extraordinary moment in Malaysian history some fifty years later beyond geographies of violence, destruction and death.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss