The personal cost of Thailand’s political turbulence is often opaque to outsiders. It was surprising for this reader to discover that Anand Panyarachun, scion of the Thai establishment, was once himself caught in the swiftly changing tides of Thai power politics. In the bout of indigenous McCarthyism that followed the October 1976 anti-student thuggery at Thammasat University, scores were also settled amongst the elites. This saw Anand, then Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, investigated as a communist sympathiser. Stood down from his position, Anand spent some weeks in limbo before being exonerated, by which time he had already decided that his career as a diplomat was over and business would be his next pursuit. It was not the last time that the outspoken public figure was to incur the wrath of powerful figures, including in military and judicial circles.

The personal cost of Thailand’s political turbulence is often opaque to outsiders. It was surprising for this reader to discover that Anand Panyarachun, scion of the Thai establishment, was once himself caught in the swiftly changing tides of Thai power politics. In the bout of indigenous McCarthyism that followed the October 1976 anti-student thuggery at Thammasat University, scores were also settled amongst the elites. This saw Anand, then Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, investigated as a communist sympathiser. Stood down from his position, Anand spent some weeks in limbo before being exonerated, by which time he had already decided that his career as a diplomat was over and business would be his next pursuit. It was not the last time that the outspoken public figure was to incur the wrath of powerful figures, including in military and judicial circles.

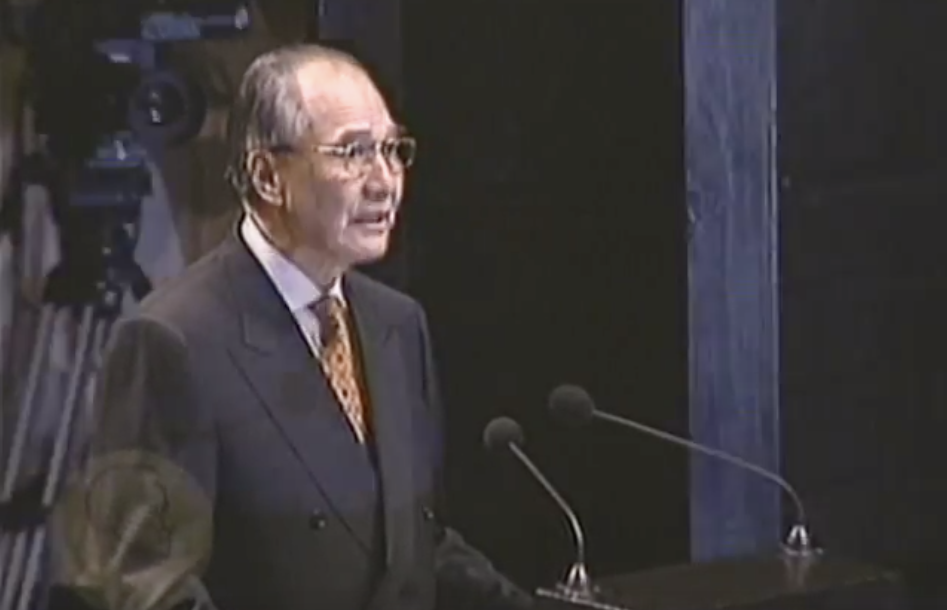

Dominic Faulder’s new biography is a very welcome addition to the rather sparse English-language offerings on former Thai political leaders. While Anand’s life was depicted in a 1999 biography in Thai, this is the first consolidated portrait in English, covering Anand’s career as diplomat, politician, businessman and philanthropist. As Faulder intends, the account of Anand’s life is also a very accessible and vivid account of Thai diplomatic and political history. Particularly well covered are two decades: the 1970s, as Thailand “separated” from the United States and its military bases, and the 1990s, when Anand as a two-term prime minister set in train what many mistakenly thought was to be a permanent democratic trajectory.

Born of a mother of Hokkien Chinese background, and a father of Mon ancestry, whose own forbears had held senior positions in the Siamese bureaucracy, Anand’s family name was bestowed by Rama VI. It drew on the Sanksrit-Pali for wisdom, panyaa and the name of the Ramayana hero, Arjuna. After growing up in Bangkok, including living through the Japanese occupation, Anand followed in his father’s footsteps with a British public school education. Schooling in England at age 16 in 1948 brought with it a tough first year of “unrelenting cultural immersion”. But by the time he graduated from Cambridge in 1955, after spending 7 continuous and formative years in England, he had become in his own words, “practically bicultural”.

Excellent English language and sharp critical thinking skills meant that after joining the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) in 1955 his career progression was rapid. Helped by a close relationship with foreign minister Thanat Khoman, Anand was appointed ambassador to the United States at tender age of 39, a position he later held while concurrently representing Thailand at the United Nations. Interestingly, at this time Anand and the Thais were elder mentors to the relatively inexperienced Singaporean diplomats, a situation that would be hard to imagine today.

Anand’s forthrightness and unwillingness to suffer fools were on display from early in his career, as was his strong belief that MOFA should lead on foreign policy. From time to time, both characteristics brought him into conflict with the Thai military, at no time more so than when he took a hard line on negotiating the terms of the exit of United States forces from Thailand under then Foreign Minister Chatichai Choonhaven. His willingness to insist on MOFA’s prerogatives on foreign policy made him enemies in the Thai military, who then sought his downfall following the 1976 violence. The account of this difficult period in Thailand’s alliance with the United States is one of the book’s highlights, as is the account of Anand’s visit to China accompanying Prime Minister Kukrit Pramoj in 1975, including meetings with the ailing Mao.

Many will also read with great interest the telling of Anand’s two formal forays into politics in the early 1990s. Never a member of any political party, Anand’s clean reputation lead to him being tapped twice for short stints as prime minister, each time as a way of circumventing political crises. The exact circumstances of Anand becoming an appointed, rather than elected, prime minister are given close attention in this book and are revealing of patterns of Thai politics, and in particular the role of the monarchy. The book also gives good accounts of key achievements of the Anand governments, including the ASEAN free trade agreement, the Cambodian peace process and the effective response to HIV/AIDs.

Anand’s direct, confident manner led some to question his “Thainess”. Certainly he was sometimes warned by colleagues to soften his approach in debating his peers and disciplining his staff. But to Tej Bunnag, a contemporary of MOFA who also ventured briefly into politics, “Anand is very Thai but of a certain kind”, with a personality reflecting his background as “the youngest son of a very distinguished family”. While it is tempting to imagine that more politicians like Anand in Thailand’s leadership class might be the solution to Thailand’s struggles with democracy, it is probably also true that his uncompromising manner would be difficult to sustain over a longer period. And while it is true the man and his political record reveal few blemishes, one area where Anand might now admit he might have done more is with respect to unionism. As Prime Minister Anand presided over legislation that one activist called “the most crushing blow ever for the Thai labour movement”. Unfortunately as this review was written, Thailand had just claimed the unenviable title of world champion of income inequality, with 1% of the population possessing 66% of Thailand’s wealth.

In his post-prime ministerial career Anand continued to sit on numerous boards, including banks, as well as take an active role in his first choice of business, Saha Union. He also worked on several international and national inquiries and commissions, including for the United Nations. Probably his most significant contribution, with many recommendations yet to be implemented, is with respect to the troubled South. Anand took charge of a National Reconciliation Commission after the violence flared again after 2004, but the political division since the 2006 coup has stymied progress. Anand remains committed to decentralisation and devolution of power to Thailand’s outer regions, not only the southern border provinces but also the north. On this score, Anand remains more liberal than many of his colleagues in the ruling elite.

A staunch monarchist, Anand has never served on the Privy Council and appears unlikely to do so. In the words of businessman Prida Tiasuwan, Anand is “pale yellow” in his approach to the monarchy. A massive reader, a gregarious and willing public speaker, with a sharp and analytical mind, Anand as a royalist democrat has been a significant contributor to Thailand’s public life and national development.Faulder’s account of his life is highly readable. It is not without some flaws; the book sometimes gets into trouble when freelancing on history. For example, the claim that Thailand never joined the League of Nations is mistaken; while it was never member of the League Council, the executive body of the General Assembly, it was an active founding member of the League itself. Anand himself seems sketchy on Siamese history. For example, when he states that Thailand as an uncolonised country was left untutored on international relations, Anand seems to overlook the role of the several capable and trusted foreign legal advisers employed by Thai kings, such as the Belgian Gustav Rolin-Jaequemins employed by Chulalongkorn or the American Francis Sayre employed by Vajiravudh.

A book cannot be all things to all readers, but there were some questions I would have liked to have seen explored. What for example, are Anand’s attitudes to Buddhism, to modern China, to the future of US–China relations? Does Anand himself speak Chinese? Based on many interviews with Anand, the book in the end is a sympathetic biography. Faulder does seek to gently challenge Anand, seeking for example his reaction to Duncan McCargo’s “network monarchy” thesis and the suggestion that he is part of this network. But the additional interviewees are also somewhat biased towards the “yellow” royalist side of politics. It may have been interesting to know how some of the Red Shirt or Pheu Thai leadership or even Thaksin Shinawatra clan remember Anand. These are however, relatively small quibbles, and the book is highly recommended.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss

Dr Greg Raymond

Dr Greg Raymond