This book is a study of Abdullah Gymnastiar, who was born in West Java in 1962. He is, however, better known as Aa Gym (older brother Gym), the name he chose to launch his career as a preacher, then to develop it as a television personality, motivational speaker, and leader of more than 20 corporate business enterprises. His “performances” and unique religious self-help program “Manajemen Qolbu”, (Heart Management) or MQ, rocketed him to pop star status for millions of Indonesian Muslims during the first decade of the new millennium. In the aftermath of 9/11 and the Bali bombings, his sermons about self-help for modern Muslims, Islamic ethics, morality, and civic duty attracted the interest of non-Muslims as well as Muslims.

This book is a study of Abdullah Gymnastiar, who was born in West Java in 1962. He is, however, better known as Aa Gym (older brother Gym), the name he chose to launch his career as a preacher, then to develop it as a television personality, motivational speaker, and leader of more than 20 corporate business enterprises. His “performances” and unique religious self-help program “Manajemen Qolbu”, (Heart Management) or MQ, rocketed him to pop star status for millions of Indonesian Muslims during the first decade of the new millennium. In the aftermath of 9/11 and the Bali bombings, his sermons about self-help for modern Muslims, Islamic ethics, morality, and civic duty attracted the interest of non-Muslims as well as Muslims.

It was Aa Gym’s reputation as a supporter of “moderate Islam”, and his influence on several million Indonesians (or more), that drew him to the attention of the Cultural Section of the Australian Embassy in Jakarta. In January 2007, they were organising an itinerary of people-to-people visits for members of the Board of the Australia Indonesia Institute (a second-track diplomacy initiative of Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade) and in it they included a lunch with Aa Gym at his headquarters in Bandung.

As a member of the Board of the AII, I met Aa Gym, who welcomed us warmly and gave us a tour of his extensive and orderly mini-village, Daarut Tauhiid (Abode of the One). We had discussions about his work and the nature of Islam in Indonesia. He invited us to return at any time and stay in the motel-type accommodation included in the complex, where thousands of his followers came for spiritual retreats. We had expected Daarut Tauhiid to be bustling with those followers, but it was quiet except for a small group of women who chatted with those of us who spoke Indonesian. A further surprise was the presence of an American who accompanied Aa Gym and introduced himself as James Hoesterey, from the Department of Anthropology, University Wisconsin-Madison. Aa Gym was the subject of his PhD dissertation and he was nearing the end of two years of field research as participant observer of Aa Gym’s activities.

Rebranding Islam: Piety, Prosperty, and a Self-Help Guru is the result of those two years observing and interviewing Aa Gym, his staff, and his followers. Aa Gym was particularly hospitable and cooperative, Hoesterey told us, inviting him to live in Daruut Tauhid and including him in many of his trips outside Bandung. To update his material for the book, Hoesterey supplemented his dissertation fieldwork with later follow-up visits, the most recent in 2014.

AA Gym with his first wife Teh Ninih (left) and his second Teh Rini (right). Photo: Liputan6 Showbiz

When I met Hoesterey in late January 2007 he must have been concerned about the future of his research, because on 1 December 2006 a journalist broke the story of that year: Aa Gym, idol of millions of Indonesians, had secretly married a second wife. His followers, especially women, felt betrayed by Aa Gym—their adviser on all matters Islamic—who had presented himself as the loving husband of the beautiful Teh Ninih, who was a religious teacher in her own right and the mother of their seven children. His disillusioned followers expressed their condemnation by shredding pictures of Aa Gym, denouncing him and his second wife on social media, and withdrawing their support for his programs and his commercial enterprises. The full impact of Aa Gym’s polygamy on his career was not evident when the Australian Embassy arranged our visit, but when we met him, Hoesterey must have known that his dissertation would become an analysis not only of the rise of a religious superstar but also his fall.

In an expansive Preface to his book, Hoesterey describes how he came to study Aa Gym and summarises the broader aims of the book in these terms: “It is about how a popular-culture niche of Sufis and self-help gurus has managed to recalibrate religious authority, Muslim subjectivity, and religious politics in post-authoritarian Indonesia.” But even within this popular-culture niche Aa Gym had succeeded in differentiating himself from other religious celebrities. He was not a Sufi nor a pesantren– or madrasah-educated religious scholar. Through the course of the book, the reader comes to see him as a highly motivated, calculating, and media-savvy performer, who enjoyed the limelight and making money. The material in the book gives little information about Aa Gym’s interior spiritual life so the reader, and perhaps Hoesterey also, is left none the wiser about this vital aspect of Aa Gym the man.

Material for the book is drawn from sympathetic Indonesian biographies of Aa Gym, from Aa Gym’s autobiographical videos of his achievements, from interviews with those who know him, including some critics, and from Hoesterey’s daily observations and personal interviews with him. When I met Hoesterey at Daruut Tauhiid in 2007, it was clear that he enjoyed privileged access to Aa Gym and his family. In the Preface, Hoesterey acknowledges his debt to Aa Gym for his willingness to trust him and involve him in so many of his activities. Hoesterey writes, “I had become part of the road show—a small price to pay for the opportunity to travel with Aa Gym around the country. Much like his devotees, and perhaps like many other ethnographic encounters, my relationship with Aa Gym was marked by economic and emotional exchange.” (p.xv).

In the context of leadership derived from religious authority, one of the main themes of his book, Hoesterey’s description of the relationship with his subject as “marked by economic and emotional exchange” is revealing. Hoesterey is, after all, not a Muslim and Aa Gym is not his leader. It can be argued that there is an affective and economic relationship between them but it is not the same as that between Aa Gym and his Indonesian followers, for whom Aa Gym’s religious authority is relevant. In Hoesterey’s case the affective relationship does not have a religious basis. Rather, it stems from an ethical and moral obligation that resulted from Hoesterey’s need for information from and about Aa Gym. Indonesian moral etiquette places the recipient of hospitality, gifts, and friendship (all of which Aa Gym gave him) under an obligation to the giver and Hoesterey would have been aware of this expectation. When Hoesterey told Aa Gym he was writing an article about his “fall”, Aa Gym told him, “Please feel free to use any documentation you have, as long as you first consult your conscience.” Both were aware that these words came with the unspoken understanding of Hoesterey’s debt of obligation.

In the context of leadership derived from religious authority, one of the main themes of his book, Hoesterey’s description of the relationship with his subject as “marked by economic and emotional exchange” is revealing. Hoesterey is, after all, not a Muslim and Aa Gym is not his leader. It can be argued that there is an affective and economic relationship between them but it is not the same as that between Aa Gym and his Indonesian followers, for whom Aa Gym’s religious authority is relevant. In Hoesterey’s case the affective relationship does not have a religious basis. Rather, it stems from an ethical and moral obligation that resulted from Hoesterey’s need for information from and about Aa Gym. Indonesian moral etiquette places the recipient of hospitality, gifts, and friendship (all of which Aa Gym gave him) under an obligation to the giver and Hoesterey would have been aware of this expectation. When Hoesterey told Aa Gym he was writing an article about his “fall”, Aa Gym told him, “Please feel free to use any documentation you have, as long as you first consult your conscience.” Both were aware that these words came with the unspoken understanding of Hoesterey’s debt of obligation.

Similarly, the economic relationship was to Hoesterey’s benefit, as he himself admits. The information Hoesterey derived from his access to Aa Gym enhanced Hoesterey’s career as an academic, just as most academics benefit materially from the information derived from living subjects who entrust it to them. Hoesterey thus walks a tightrope between obligation towards and familiarity with Aa Gym and the objectivity required for academic research and analysis. In this reader’s estimation, Hoesterey’s affective and economic relationship with his subject has sometimes made him wobble on the tightrope, tilting him closer to Aa Gym and away from objective analysis. These wobbles are evident when he recounts some of Aa Gym’s self-revelatory remarks without further discussion, even when they can shed light on Aa Gym’s character and motives. For example, without establishing a date for the quote or remarking on its significance, Hoesterey writes, “‘Media are like water buffalos,’ Aa Gym once told me. ‘You just have to lead them by the nose ring.’” (p.155). The thinking reader might wonder what implications and consequences this attitude has for Aa Gym’s affective and economic relationships with all his contacts.

Hoesterey presents an engaging and perceptive account of how Aa Gym constructed his trademark “brand” of religious authority: through his trendy yet semi-religious dress (trademark turban, well-tailored white jacket and dark trousers); discourse (feel-good homilies drawing on the Qur’an, the example of the Prophet Muhammad, and Aa Gym’s own life stories); and the supportive advice that he delivered with humorous anecdotes and in a “soothing psycho-therapy tone”. Hoesterey describes Aa Gym’s approach to his religion as “Islam was not just a religion to be lived but also a product to be packaged and sold.” (p.35) For many Muslims the idea of making money from their religion is anathema, so not all Muslims would respond to the commodification of Islam, especially when it is for personal gain. As the work of Fealy and White, and other scholars has shown, however, millions of Indonesians do “buy” Islam and it was to this market that Aa Gym made his pitch.

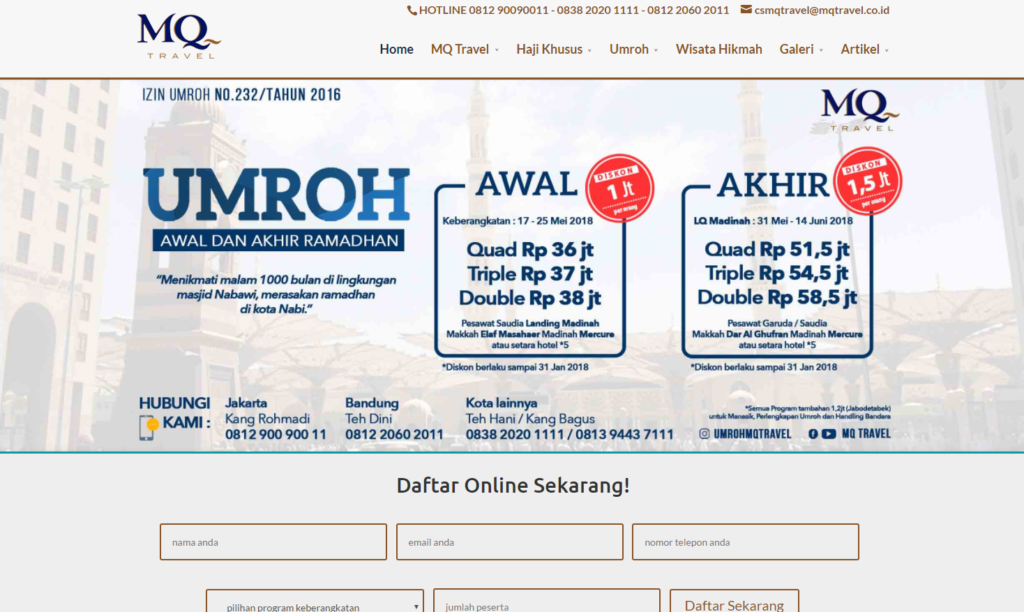

The website of MQ Travel, promoting Hajj and Umroh packages (trips together with AA Gym himself command a premium)

Hoesterey provides an excellent overview of the products that AA Gym developed, trademarked and licensed, and delivered. These included his flagship MQ (Heart Management Program) presented through “nationally televised sermons, self-help books, and Islamic training seminars”; the MQ Blessings firm that produced and marketed food, drinks, clothing and personal items; and also the entire Daarut Tauhiid enterprise with its bank, restaurants, souvenir and other shops and spiritual tourism facilities, as well as TV production studio and publishing house. Over twenty businesses were listed under the organisational umbrella of the MQ Corporation.

At least 700 staff, all dependent on his brand for their livelihoods, met every Monday morning at Daarut Tauhiid to listen to a pep talk by Aa Gym. As well, a significant number of “trainers” found work under the Aa Gym brand, teaching people how to apply various pseudo-psychology and self-help (or as Hoesterey says, “self-engineering”) programs for which they charged substantial fees. For example, a pre-retirement entrepreneurship program designed for 200 Bank Mandiri employees brought in $US100,000, and other programs regularly brought in similar sums. Hoesterey describes how two skilled Indonesian executives working for Aa Gym designed a program that adapted elements from American positive psychology thinkers—including from Tony Buzan’s “mind mapping” and Edward de Bono’s problem solving techniques. These Indonesian super-trainers “consciously tried to find the Islamic textual resources that could support the science” so that the programs appealed to Indonesian Muslim corporate executives. (p.112). In Hoesterey’s words, “… Aa Gym and the Muslim trainers transformed scientific knowledge into religious wisdom and also re-packaged and promoted transnational scientific discourse through print, radio, television and training sessions.” (p.96)

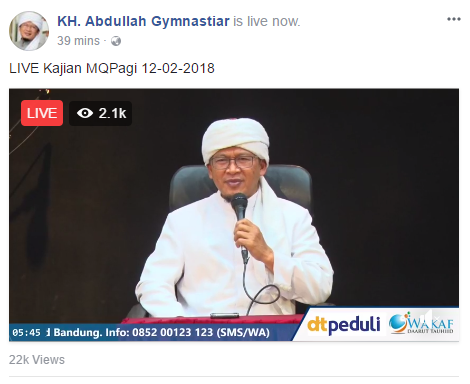

AA Gym’s morning broadcast on Facebook

I take issue with Hoesterey’s use of the word “scientific” to describe the information Aa Gym was appropriating and re-packaging under that label. At best that “knowledge” is pseudo or popular science. Hoesterey acknowledges this only in a footnote concerning the properties of “Hexagonal water”, properties “discovered” by the Japanese Dr Masaru Emoto. This “special” water was promoted on the basis of its “hexagonal crystals” and their alleged miraculous powers. In fact, as Hoesterey’s footnote explains, hexagonal crystals are present in all water. Products such as these were endorsed by Aa Gym, promoted in seminars at luxury hotels, and sold by franchises using pyramid sales techniques.

The book does not address the scale and destinations of the profits made by companies under the MQ Corporation umbrella. There are references to Aa Gym seeking financial backers for his programs and Hoesterey notes that Aa Gym’s private wealth gave him the flexibility to finance his own initiatives if necessary. But there are no further details about that private wealth. Perhaps Hoesterey was unable to gain that information, but a full understanding of the Aa Gym phenomenon is incomplete without consideration of who benefitted from the financial benefits of the enterprises and how the profits were used.

Nowhere does Hoesterey clearly point out that Aa Gym and his backers are duping followers and customers by claiming products such as water with special powers have been scientifically tested for their properties. The claims that the Aa Gym brand makes for its products are sometimes misleading, or worse, fraudulent. If the Islamic terminology designed to “Islamise” the products were to be stripped away, those products could be evaluated using the secular criteria of performance and value for money. Those selling the products might be charged with misleading advertising and forced to return money to their customers. The Qur’an condemns fraudulent dealings, but law enforcers seem reluctant to apply the usual norms of trading to “religious” products. It is an indication of the hubris of Aa Gym and his backers that they believed they could sell anything under their brand and escape investigation of their claims.

It was not, however, his commercial enterprises, but Aa Gym’s own behaviour that brought down his corporate empire and undermined the credibility of his religious authority. The Indonesian media broke the story of Aa Gym’s secret second marriage at the beginning of December 2006. Hoesterey does not comment on the coincidence of timing between Aa Gym’s active campaigning in support of anti-pornography legislation (and his star performance at a public hearing about the legislation in February 2006) with his decision to marry a second wife. The polygamous marriage must have happened around that time or soon after. The coincidence would not have escaped his followers, and his public professions of piety and morality compounded their perception of his hypocrisy and insincerity.

Hoesterey’s analysis of the Aa Gym “brand” emphasises that it depended totally on the support of Muslims who acknowledged his religious authority. He refers to those Muslims variously as “followers”, “admirers”, “disciples”, or “devotees”. He rarely refers to them as “consumers”, “customers” or “clients”, even though he describes their relationship with Aa Gym as one based on “economic and emotional exchange”. Hoesterey’s summary of Aa Gym’s “fall from grace” describes it as the “economic and affective exchange relationships between a preacher-producer, corporate consumers, and fickle devotees”. This description does not acknowledge that the “fickle devotees” had been groomed by Aa Gym and his trainers to “consume” the Aa Gym brand in order to become better Muslims. A vocal number of those Muslims felt let down and duped by their leader’s personal behaviour, so perhaps “fickle” more appropriately describes Aa Gym and his self-serving interpretations of the Qur’an and Sunna.

Piety, politics, and the popularity of Felix Siauw

An ethnic Chinese convert to hardline Islam stands out in Indonesia’s crowded Islamic preaching market.

Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah offer programs in areas like Islamic psychology, domestic violence, entrepreneurship, leadership, social justice, and disaster relief but clearly there remain unmet needs. The Aa Gym phenomenon shows that enterprising marketers are continually working to identify those unmet needs. Their method is then to select a trendy pseudo-scientific template and fill it with content perceived to be Islamic. The sales team and teams of trainers and promoters can then spring into action backed by one or several of Indonesia’s corporate billionaires. If the seekers and followers go for the product, politicians will also lend their support to its promoters.

Hoesterey’s study includes many examples that indicate the age-old Indonesian creativity for syntheses between local and global influences is alive and thriving. He pays less attention to local West Javanese influences on Aa Gym’s expression of Islam. He does mention Imaduddin Abdulrahim’s training programs and campus outreach movements during the late 1970s and early 1980s, but does not refer to Rifki Rosyad’s very useful overview of the Islamic resurgence among Bandung’s young Muslims during that period including descriptions of the training sessions in Salman Mosque. Perhaps even more relevant to the honing of Aa Gym’s performance style is Julian Millie’s research into the techniques used by popular preachers in West Java.

Hoesterey’s book will be welcomed as a text for anthropologists, and not only those who study Islam in Indonesia. All readers will find this analysis of the rise, fall, and return of a honey-tongued preacher and entrepreneur intriguing. They will also find that its approach and carefully assembled materials provide the basis for lively debate, discussions, and gendered readings of Aa Gym’s attitude to women.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss

Virginia Matheson Hooker is Emeritus Professor and Fellow in the Department of Political and Social Change at the Australian National University’s College of Asia and the Pacific. She retired as Professor of Indonesian and Malay in January 2007. Her research has focused on Islam in Southeast Asia, literature and social change in Malaysia and Indonesia, and Indonesian political culture. Her most recent book, co-edited with Associate Professor Greg Fealy, is

Virginia Matheson Hooker is Emeritus Professor and Fellow in the Department of Political and Social Change at the Australian National University’s College of Asia and the Pacific. She retired as Professor of Indonesian and Malay in January 2007. Her research has focused on Islam in Southeast Asia, literature and social change in Malaysia and Indonesia, and Indonesian political culture. Her most recent book, co-edited with Associate Professor Greg Fealy, is