Sudhir Thomas Vadaketh, Floating on a Malayan Breeze: Travels in Malaysia and Singapore

Hong Kong and Singapore: Hong Kong University Press and NUS Press, 2012. Pp. viii, 282; map, photographs, notes, index.

Reviewed by Elvin Ong.

Ever since Singapore’s split from Malaysia in 1965, the government of each country has been bent on directing its trajectory away from that of the other. This tendency perhaps peaked during the governments of the two countries’ most renowned authoritarian leaders, Lee Kuan Yew and Mahathir Mohamad. Singapore was always going to be what Malaysia was not. Malaysia was always going to go its own way, irrespective of what Singapore did. So dominant are the two opposing caricatures that have emerged – one clean, one dirty; one efficient, one corrupt; one carefree, one perpetually stressed – that we very often forget that Singapore and Malaysia have a shared past in British Malaya and that they have always been dependent on each other, at least in the economic realm.

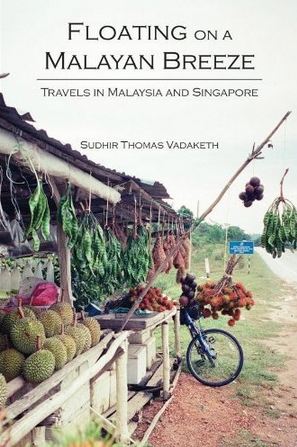

In an attempt to correct this view, Sudhir Thomas Vadaketh, the Singaporean-born son of a Malaysian-born father, declares early in Floating on a Malayan Breeze that the book is his attempt to provide what has been a missing “bottom-up perspective in national discourse” by writing about the two countries “as seen from the ground” (p. vi). On the one hand, he relates encounters with random personalities from Singapore, with people met during his month-long biking expedition around Peninsular Malaysia in 2004, and with various interesting individuals whom he interviewed on the ground during the campaign for the watershed 2008 Malaysian elections. On the other, he shares pieces of personal insight about the socio-political development of the two countries in the past decade. The resulting book is part travelogue and part socio-political commentary, a somewhat frustrating combination that is enjoyable, but that also raises more questions than it answers.

Sudhir’s vivid descriptions of his interviews and of the challenges encountered during his travels in Malaysia often set the stage for his larger points. Throughout the book, we are drawn into his conversations with various “big” and “small” personalities across the political spectrum in Malaysia. Some “big” personalities include Steven Gan, co-founder of the Web-site Malaysiakini, and Nurul Izzah, the incumbent member of parliament for Lembah Pantai – better known, perhaps, as the daughter of Anwar Ibrahim, the de facto leader of the political opposition to Malaysia’s Barisan Nasional government. The interviews with such “big” individuals are useful to the extent that they provide a sliver of insight into these individuals’ backgrounds and their motivations for driving socio-political change in Malaysia today.

But as Sudhir demonstrates, “small” characters often have important, sometimes much more important, stories to tell. Betty owns a nondescript souvenir shop just across the border from Malaysia in Betong, Thailand. She was a former guerrilla soldier with the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM), which fought against the British, Japanese and newly-independent Malayan and Malaysian governments for a Communist Malaya. She is uniquely positioned to help Sudhir excavate a broader point about the CPM’s forgotten role in Malaya’s independence movement. Mr Liew is a Chinese businessman and eager supporter of the Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) in Kota Bharu, Kelantan. He punctures the stereotype that PAS is an extremist Malay political party that does not know how to “do” development. In a sense, these colourful “small” characters like Betty and Mr Liew are the gatekeepers for forgotten or interesting stories. They give life to staid political-science theories and dull academic writing.

Yet, for all the fascinating interviews and insights that Sudhir’s encounters with such people provide, it is difficult to make sense of them in a coherent manner, except in the context of Sudhir’s personal interpretation and commentary. Although he tries his best to make many good points about many salient topics, this is also where the book hits some serious snags.

First, and even if we set aside the dire lack of a common thread running through his book (a lack due to its being written, in part, on the basis of random encounters during a bicycle expedition), Sudhir dithers between perpetuating stereotypes about Singapore and Malaysia and countering those stereotypes. As the book’s title suggests, Sudhir constantly “floats” between repeating official dominant ideologies and noting the various instances in which they require qualification, so much so that one cannot quite conclude what to make of the issue. For example, in the process of stressing the divergence between race-conscious Malaysia and race-neutral, meritocratic Singapore, Sudhir brings up so many qualifications to the idea of meritocracy in Singapore that one wonders if they negate the entire hegemony of meritocracy at all! He notes that senior management from India working in Singapore often hire their own kind, that he himself suffered from racial stereotyping when growing up, that the Singaporean Malay-Chinese taxi driver Ishak vows to retire in Thailand because he can no longer tolerate the racial stereotyping in Singapore, and that Malay Singaporeans still cannot serve in sensitive sectors in the Singapore Armed Forces. It appears that Singapore – both the government and the people – is as race-conscious as Malaysia after all.

Second, Sudhir often ruminates on a wide variety of important social issues in the two countries – media control and censorship, the nascent development of civil society, the influx of immigrants, the growing income gap, bumiputera affirmative-action policies, religiosity, family planning and urban stress – without actually coming to any definitive conclusion about what indeed should or will be the way forward. This deficiency is most clearly exposed in two chapters discussing the gradual decline of the United Malays National Organisation in Malaysia and the People’s Action Party in Singapore. After much discussion of race-based politics in the former party and the iron cage of group-think in the latter, Sudhir concludes with a meek “It will be interesting to see how long they last” (p. 92). While some students or casual readers may find this conclusion satisfying, serious academics will find such a concluding line entirely frustrating. Where is the comparative theory on authoritarian regimes?

Third and finally, while as a fellow Singaporean I strongly concur and empathize with Sudhir’s description of recent trends in Singapore society, I cannot help having the nagging feeling that both of us are trapped with the same stereotypical worldview and narrative of what Singapore is, with both of us having good university educations and mixing in similar circles. (Full, though late, disclosure: I met very briefly with Sudhir at the videotaping of a debate about Lee Hsien Loong and was an intern in the Civil Service College under Donald Low, one of his few Singaporean interviewees.) What would be the worldview of the young Singaporean McDonald’s deliveryman? Or the elderly cashier at NTUC FairPrice supermarket? Or the uncle sipping his potent brew of Guiness or Heineken and ice cubes at the local coffee shop? Or the multitude of people who queue up in the wee hours of the morning for a chance to buy a “Hello Kitty” toy from, again, McDonald’s? There is a reason that Jack Neo, arguably Singapore’s most successful movie director as measured in box office receipts, consistently makes movies that break record after record at the cinemas, even though many educated intellectuals find his movies generally crass and distasteful. Perhaps Jack Neo understands the Singaporean psyche better than we do? Are we already victims of the growing inequality that we constantly deride?

Floating on a Malayan Breeze serves as a good introductory text for readers unfamiliar with Singapore and Malaysia, or for students and the general public who have for far too long been fed state-endorsed narratives of the history and social development of their respective countries. The book’s vivid and somewhat witty writing brings many of its interviews to life, and, before long, the reader will find an unconscious smile creeping across his or her own face as he or she ponders what is unfolding between Sudhir and the interviewee. But this book is no serious academic research. Random sampling does not necessarily result in a representative sample. Anecdotal evidence is not robust evidence. Scholars who already know both countries well may be able to glean some nuggets of interesting insights, but they are unlikely to advance their knowledge of the two countries in any serious way.

Elvin Ong is an incoming doctoral student in political science at Emory University with an interest in the varied performances of politics in Southeast Asia.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss