Trilogi Indonesia Menghadapi Perubahan Iklim, a trilogy of books, interrogates how Indonesia has been responding to the social-ecological, political and economic impacts of climate change. As a series, the books provide a fine overview of how complex climate change policy responses and civil-society initiatives have affected both local communities and society at large. Key questions that this book attempts to address include: what are key barriers in delivering programs at national and local levels? What are the challenges to scaling up good practices established at the grassroots level? How can we measure the success of climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts? How have climate change policy and programs affected local communities, particularly vulnerable groups?

Indonesia is a major carbon emitter, especially when it comes to rapid, undocumented and unsustainable land-use and land-change (such as in the form of forest and peat fires), on top of transportation and manufacturing-based emissions. Indonesian scholars on climate change and environmental justice are aware that there are wide-ranging mitigation and adaptation policies and programs implemented on the ground, led variously by the central government, regional and local governments, the private-sector and civil society. Knowledge about these efforts, however, remains scattered and relatively segregated, especially between geo- and bio-physical sciences and the social sciences. In particular, we know little about how climate change itself and policies affect Indonesia’s most vulnerable local communities including landless peasants, women, children, the elderly, indigenous communities, and traditional fisherfolks in coastal and small islands. Editors of Trilogi Indonesia Menghadapi Perubahan Iklim have managed to bring it all together, while attempting to provide a view of the implications and complexities of policy implementation from the bottom-up.

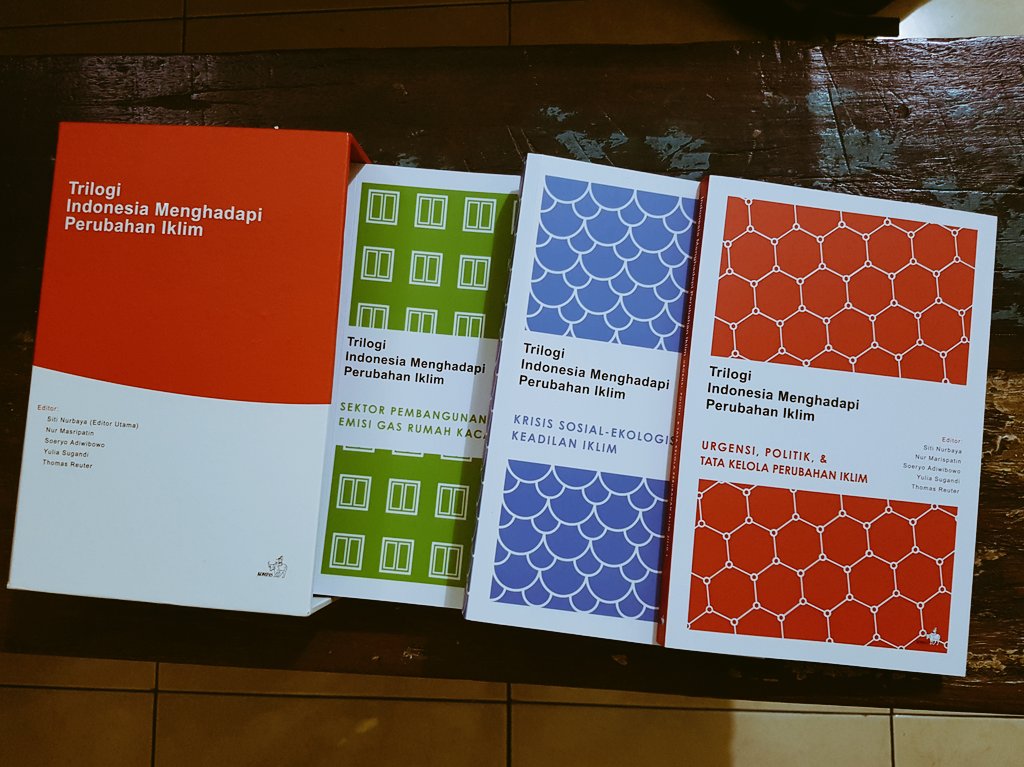

Image credit: Twitter user margianta

Trilogi Indonesia Menghadapi Perubahan Iklim comprises a compilation of analysis and reflection from policymakers, CSOs, researchers and academics. Book One puts Indonesia’s gas emission reduction efforts in historical perspective, overviewing developments such as improvements in technology and governance, the transformation of institutional arrangements in response to global and local needs, and changing national development agendas. Book Two covers diverse topics of public policy, ranging from carbon trading, to the impacts of climate change on public health, to financing climate change mitigation. Book Three examines issues of climate justice and social-ecological impacts, including impacts on coastal and small island communities, community-based restoration efforts and youth-led waste management initiatives.

As a trilogy, the series provides a useful overview of the climate change situation in Indonesia, while locating the country within regional and global cooperation. In organising pieces for the book, editors did well in going beyond the binary of ‘mitigation’ and ‘adaptation’ to climate change, while attempting to cover a broad range of actors participating in collaborative action. The books contain direct perspectives from policymakers, researchers, academics and members of civil society on their ambitions for Indonesia in working through existing and future impacts of climate change, how Indonesia can deliver its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) as part of global efforts to reduce gas emissions, and the consequences for the most vulnerable in society.

In saying this, several things can be improved for the next comprehensive work on climate change in Indonesia. First, expanded documentation of indigenous voices is needed to capture their unique experiences, responses, challenges and aspirations. There is much to learn about sustainable use of forests, land, water and the sea from indigenous practices where resource use is fundamentally tied with conservation. Customary bodies (majelis hukum adat) and indigenous networks, including indigenous women networks (persatuan perempuan adat nusantara), enable indigenous knowledge and practices to be implemented, shared, and potentially replicated in other places when suitable. The Indigenous Women Alliance, Perempuan Adat AMAN, has been at the forefront of practicing mitigation and adaptation to climate change, and facilitating knowledge sharing among broader communities on land and forest use and conservation.

Second, the books regularly repeat certain jargon without adequate explanation for lay readers, including ketahanan iklim (climate resilience), pembangunan rendah karbon (low carbon development) and deep decarbonisation. How these concepts complicate or are linked to climate change need elaboration.

Third, despite the trilogy’s efforts to provide a holistic view of climate change in Indonesia, several case studies maintain a central-government viewpoint that overlooks the great potential of learning from the grassroot perspectives of regional, local government and non-governmental efforts. For example, the reader would be left with the impression from Book Three that monitoring and evaluation of peatland restoration is performed solely by national-level governmental bodies due to lack of local nuances.

Trilogi Indonesia Menghadapi Perubahan Iklim is a collective celebration, reflection and vision of how Indonesia has been and ought to deal with climate change in the past, present and future. This book deserves more attention from policymakers, academics and indeed anyone keen to learn about the impacts and responses to climate change in Indonesia. Though the book is still only available in Bahasa Indonesia, the trilogy provides a rich overview of the networks of actors and institutions involved, from perspectives including gender, social and environmental justice, and human rights.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss