In modern Malaysia, attitudes born in the traditional village, as well as Islam, are being used to defend against threats to the Malay world’s important symbolic boundaries.

I ended some recent remarks on the current political situation in Malaysia with an allusion to what I call ‘deep’ Malay cultural psychology. I noted that:

They, so many of them, would rather have to themselves, unshared and exclusively ‘on their own terms’, 100 per cent of a small and dubious inheritance — to squabble over interminably among themselves — than to have and enjoy a substantial stake in a thriving enterprise that they must share, sensibly, in both material gratitude and human generosity, with others. More on this ‘Malay cultural psychology’ another time…

Well, that time came sooner than I expected, so I have written on the subject. This is not a final statement but should be considered a first draft. Note well and bear that in mind as you read it.

First, let’s be clear about what I am not talking about here. I am not talking about the now standard clichés, even these days generally ‘received ideas’, promoted and popularised by Tun Dr Mahathir in his The Malay Dilemma (subsequently recycled, little changed or modified, in some parts of his memoir, Doctor in the House).

Nor am I speaking of the important ideas and debates that Tun Dr Mahathir should have been aware of (but probably was not) when he wrote The Malay Dilemma. These included the controversy that briefly raged in the late 1960s, especially between the economist Brien Parkinson and the anthropologist William Wilder Jr, about the non-economic aspects and sources of what was then called ‘Malay economic backwardness’.

I am not talking about the key ideas upon which that debate rested, found especially in the work of the anthropologist Michael G Swift exploring the formative sociocultural groundings and cultural-psychological dimensions of Malay economic attitudes and behaviour.

Nor am I speaking here about the bearing upon these same questions at the time and since of Syed Hussein Alatas’s critique of ‘the Myth of the Lazy Native’ in the wider Malay world of Southeast Asia.

Neither am I alluding to some more general ideas upon which that debate and those arguments in part rested: ideas, again, to which people now habitually have recourse in discussing many issues of this kind, while remaining totally innocent and ignorant of any idea of their origins. These are namely the clichés — so much a part of the fateful policy debates of 1969-1970 leading up to the declaration of the New Economic Plan — of a ‘limited pie’ , of ‘dividing up the cake’ and of ‘increasing the size of the economic cake’ to be shared.

These expressions and ideas had their origins in a once famous but now largely forgotten essay by the anthropologist George M Foster on “Peasant Society and the Image of the Limited Good”. These are ideas about whether it is better to argue about the proportional sharing, or division, of a given fixed quantum (‘zero sum’ thinking in Game Theory talk) or to work instead to increase the size of the overall yield that is to be shared among a number of parties.

These ideas are often, in one way or another, drawn into the discussion about Malay and Malayan and Malaysian society: into arguments about ethnic relations, separation, competition and Malay anxieties and fears of being out-competed by (non-Malay) others.

But important as these ideas are, in general, and in the modern Malaysian policy and political context, I am not talking here simply about those things, but something much deeper.

So, what then am I talking about?

I am calling attention here to matters that anybody who has ever spent a night, or several, or a week or several, in a Malay village — and especially anybody who has spent a few evenings, and long nights until dawn, with some Malay village bomoh (or shaman) as they have gone about their special business — will know about. And if you haven’t, you probably won’t. But need to.

This has to do with a fundamental Malay cultural sense of ‘beleaguerement’, and of the ensuing need of Malays to huddle close together — sometimes behind physical barricades such as bamboo perimeter fences and often behind less tangible protective barriers — in mutual support.

These ideas, upheld as experientially powerful cultural imperatives, long predate, and have much deeper sociocultural origins than, what we may call modern plural society social dynamics and stresses — though they may well feed into modern historical and now also contemporary Malay ideas about, attitudes toward, and anxieties concerning economic competition and fears of social displacement and marginalisation.

I am talking here about matters that were once of interest and concern to that largely forgotten, and now widely scorned field of knowledge — old-fashioned (pre-postmodernist) social and cultural anthropology.

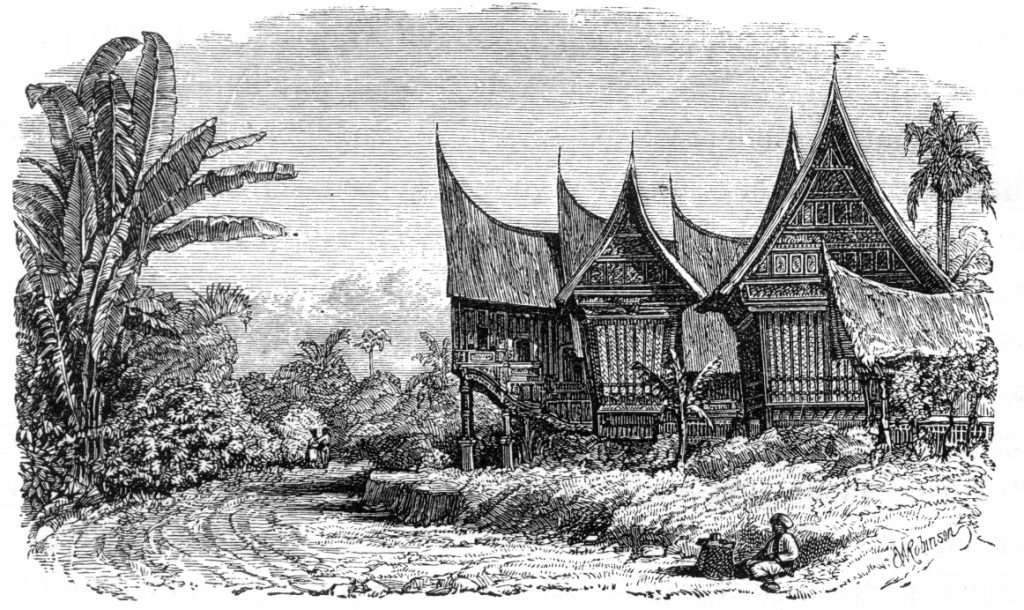

If you have ever been in a ‘conventional’, quasi-traditional Malay village at nightfall, as the evening suddenly closes in and the swooping dark suddenly envelopes people at day’s end, as senja (dusk) arrives with all its mambang (hauntings) and other strange, disquieting mystical forces, you will know what I am talking about.

A perceptible apprehensive hush descends, and with it a fear of disturbing who knows what.

Understandably, the villagers think (or that is how things were), they hope and trust in the idea, that there is safety in numbers. So they try to huddle together defensively, united in protective agreement against those fears, spoken and unspoken. It gives them strength, or a feeling of strength, it makes them feel secure.

When Malay villagers in former times felt themselves threatened — by human enemies, by wild animals, by plague and illness, by the supernatural terrors of the surrounding jungle, by the dark and all the unseen dangers that it might conceal — they would huddle together for strength. They would find assurance in and seek protection from the spirit-challenging jampi (spell) of a bomoh and would recite do’a, Islamic pleas and prayers. Together, they would chant especially potent verses and sura from the Quran for protection from encroaching evil.

Photo: Cccefalon/ Wikimedia commons

What is the modern relevance of all this? It lies in the fact that, while the traditional Malay village may no longer exist, the attitudes born in and of its cultural milieu still do. And they continue to exert a powerful force upon modern Malays, in the countryside and city alike.

In a similar way, overall, to that older village social universe, the Malay political world in peninsular Malaysia these days huddles together for reassurance, in kampung-like strength and solidarity, behind a barrier and fortification that is afforded largely by Islam — an Islam under royal patronage and protection and of constitutionally guaranteed standing. It is the old strategy of kampung defence, now writ large.

Through recourse to Islam, threats to the integrity of the Malay world’s important symbolic boundaries can be contained. Islam is used to insulate the boundaries of Malay society against non-Malay intrusion, penetration and subversion — to separate Malay society symbolically and morally from, and elevate it beyond the reach of, its threatening, even contaminating, wider social environment.

We are all familiar with the concept and historical creation of Malay Reservation Land. More recently the same process of space-management has been extended to other areas, to virtual space. Specifically, to linguistic space.

In the contentious ‘name of Allah’ dispute — and notably in then Court of Appeals Justice Apandi Ali’s astounding landmark decision in the matter — as well as in the case of words such as agama, ibadah, iman and the 30 or more others that are now on Malaysia’s quasi-papal index of religious terms (istilah) that are for exclusive Muslim use only, and not to be applied to the discussion of any and all non-Muslim religious life, we see this process not just advancing but assiduously and officially promoted.

We now have, and people are asked to recognise and accept, an entire new privileged zone that has been set aside, that of “Bahasa dan Istilah Rizab Melayu”, of a quarantined Malay Reservation in language and terminology. A Malay semantic protectorate. One with Islamically patrolled and fortified boundaries.

This barrier of protective prohibitions is the modern equivalent of the recourse of Malay villagers to chanting do’a in the dark to ward off wild beasts, malign spirits, strangers or encroaching outside plagues such as cholera.

These modern practices, this array of duly gazetted bureaucratically sustained prohibitions, also provide a protective barrier, an insulating buffer device, enabling beleaguered Malays (or those who feel that way, and who have the power to impose their ways, likes and fears authoritatively on others, on all Malays) to huddle together, secure among their own kind, for reassurance and distancing protection.

This is what, at the deep cultural and psychological level, lies behind, informs and drives the continuing Malay determination to live huddling together for comfort and strength — rather than being eager, ready, or just prepared to engage with others and seek sensibly to share the world with them. They would rather have a smaller, narrower world, but one that is their own, entirely their own, that they may inhabit and hold exclusively on their own cultural terms.

The outside world, the world that surrounds the Malay world, closes in upon it, and asks Malays to engage with it on its broader and more inclusive terms is, somehow, the analogue and functional equivalent of, and is psychologically isomorphic with, the non-human, asocial, non-Malay world of mambang and ghosts, of spirits and wild animals, of strangers and the unknown, that closed in upon the ‘little Malay world’ of the village every night.

Clive Kessler is Emeritus Professor of Sociology and Anthropology at the University of New South Wales, Sydney. He is the author of many works in this area, most notably Islam and Politics in a Malay State: Kelantan 1838-1969.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss