“When the defendants come in, we ask that the relative cooperate and not get up to give them a hug na ka” a court officer in blue requested as I surrendered my cell phone in the courtroom.

What a specific request, I thought. I remembered the many hugs given two Mondays earlier, on March 15, to defendants in the high-profile political case when they were brought from prison to the Criminal Court. Even us friends and fans, otherwise barred from entering the courtroom, could wait in the hallway for the opportunity to say hi, shake hands, and hug as they were escorted in and out.

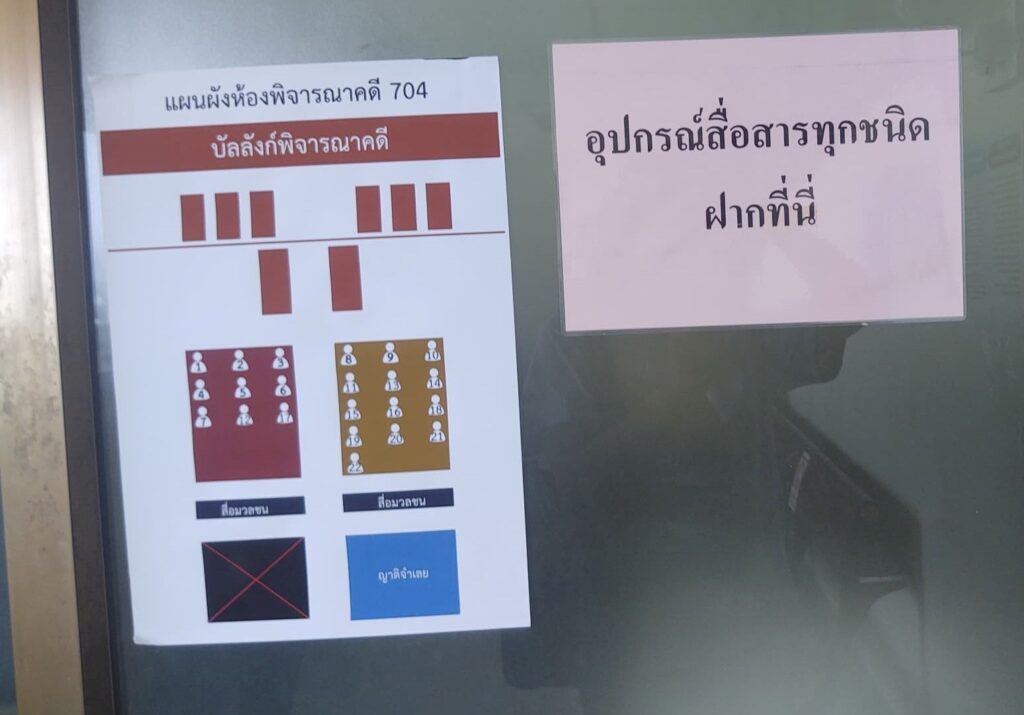

With this no-hug policy, the Courtroom 704 Diagram on the door suddenly made sense. It placed the relatives in the light blue zone precisely to prevent them from reaching the defendants, who would be escorted in from the bottom left corner to their seats in the red zone, sandwiched between two correctional officers at all times. They would be so far away I’d later wish for a pair of binoculars.

Pictured: Courtroom 704 Diagram on March 29, 2021. From the top: the bench, the prosecutors and defense lawyers, the defendants, the press, and the relatives. The sign on the right says, “All communication devices shall be deposited here.” (Image supplied by the author)

That day, 29 March 2021, was scheduled for the examination of pre-trial evidence in cases against twenty-two defendants, prosecuted for their actions in the peaceful pro-democracy rally on 19 September, 2020. Seven were charged with lese majeste on top of other charges; the rest, sedition.

Apart from lawyers, only two relatives per jailed defendant were let in the room. And there were nine inmates—Parit “Penguin” Chiwarak (#1), Arnon Nampa (#2), Patiwat “Morlam Bank” Saraiyaem (#3), Somyot Prueksakasemsuk (#4), Panusaya “Rung” Sithijirawattanakul (#5), Panupong “Mike” Jadnok (#6), Jatupat “Pai” Boonpattararuksa (#7), Chukiat “Justin” Saengwong (#12), and Chai-amorn “Ammy” Kaewwiboonpan (#17). The remaining defendants were placed in the yellow zone. The dark blue zone was for journalists, but only three or four were let in. The proceedings were set for nine o’clock. Minutes before noon, the judges finally appeared.

“The Court has descended (saan long laew ka),” said the same policewoman in our direction. We all shut up and rose.

I made a mental note of the use of “descend.” Into the courtroom descend the judges, via a special door to the dais up front against the backdrop of King Bhumibol and King Vajiralongkorn’s portraits. The defendants, meanwhile, ascend: the Thai phrase khuen saan which means “go to court” also recalls the experience of going up the Court’s grand granite steps.

Then, from the back, the defendants entered. The room was chilly; I imagined it must have been cold for the inmates who walked in barefoot. Or wheeled in—Penguin was on Day 14 of his hunger strike and came in a wheelchair with an IV attached. As Penguin came in, his mother Sureerat Chiwarak got up and made silent gestures. Immediately she was told to sit by court police. Penguin managed to angle up his right hand and make a three-finger salute. Quickly the hand was covered and pressed flat against the armrest by a correctional officer.

This action-reaction sequence would replay many times in the courtroom. For example, the court policewoman told Sureerat to go back to her seat even after the Court granted her the approval to go check up on Penguin; a small kerfuffle ensued. Hours later, as the Court announced its end-of-day deliberations, Sureerat was told to rise but shook her head and remained seated. Or, as Rung read her statement to the Court and vowed in tears to join Penguin in a hunger strike, a three-finger salute was raised in the yellow zone. That same policewoman, her hair tight in a bun below a blue beret, pinched her hand on the back of a younger officer, physically pushing him to go take that hand down.

From time to time, the Court would grant approval to this mother or that father to go talk to a defendant. Once, the Court explicitly allowed Pai and his father-lawyer to talk to each other without correctional officers in hearing distance. At such moments, a feeling of gratitude would start to well up in me, and I had to pull myself back: don’t fall for their good cop/bad cop routine. Didn’t the Court co-sign, if not design, all of this extension of prison into the courtroom?

Behind the student protests for reforms to the monarchy that are shaking the century-old foundations of Thailand's political system.

The ten demands that shook Thailand

In an interview, Sureerat provided a catalog of all the petty ways petty court and correctional officers had tried to keep her from prison visits and courtrooms. The pettiness suggests something quite grave, as Sureerat recounted:

Pictured: a yellow barrier they put in front of Courtroom 701 in the morning of March 15, 2021 (Image supplied by the author)

“In the late afternoon, some officer/s even came up to me and said that this kind of treatment was excessive. I only learned that day that this was like what they’d do to inmates slated to be executed. They told me that inmates sentenced to death would be prohibited from seeing their relatives due to snatching concerns. But in this case nobody has even been convicted.”

And it got worse. In the following appointment, on April 7, citing an emerging wave of COVID-19 cases, the Court prohibited all relatives from going anywhere near the courtroom or the elevator leading to it. After much protesting by the mothers and the lawyers, one parent per defendant was allowed to go in the courtroom for ten minutes.

The presiding judge proceeded to ask each parent if they could convince their child to accept the “conditions” if they were to be released on bail.

What kind of justice directly bargains with a defendant’s mother like that?

* * *

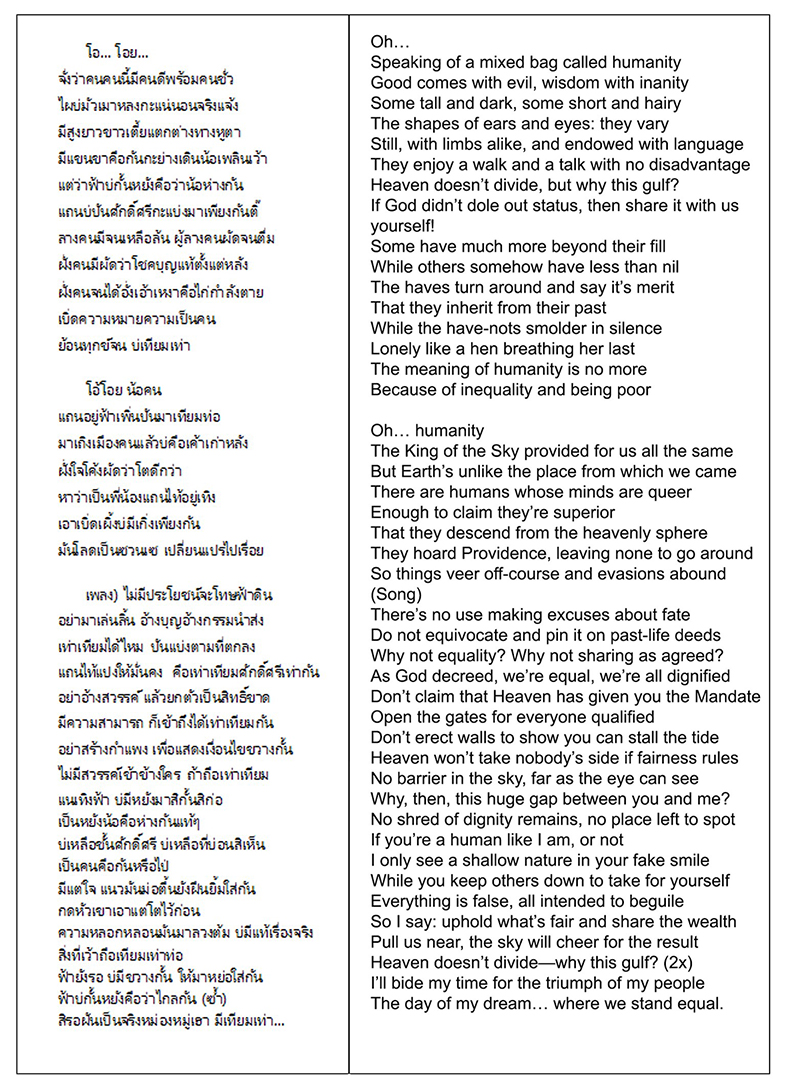

As I was stranded in the back of that courtroom, and for days afterward, one sentence echoed in my head: heaven doesn’t divide—why this gulf?

It’s a line from the song ลำเพลิน ฟ้าบ่กั้นหยังคือว่าห่างกัน by Morlam Bank (#3), “morlam” doubling both as the title used by Isan Lao folk singers/performers, as well the name of their musical tradition, from northeastern Thailand. After the coup in 2014, Bank spent two years in prison, convicted of lese majeste for his role in a 2013 play. Bank wrote the song in 2015 and has performed it a few times since his release.

Four years after serving his initial sentence, Bank was charged with lese majeste again, this time for speaking about being a victim of royalist persecution at a rally. Prompted by the judge, Bank accepted the conditions of not participating in any gathering that tarnishes the institution’s name and not mentioning the monarchy again, ever (yaang det khaat). He offered, additionally, that he was okay with being confined to the kingdom and that the Court could revoke his bail if he missed an appointment.

When I learned of the four conditions, I asked myself: would a performance of songs like “Lam Ploen Heaven Doesn’t Divide—Why This Gulf?” be taken to be a breach of the conditions? How much of himself is Morlam Bank offering up as sacrifice? To answer these questions, let us gather round a virtual morlam stage and watch Bank perform this song, up close and personal.

Does this song mention the monarchy? Do the “humans whose minds are queer” (fang jai khong) refer to royalty? Does the reference to “God” (Thaen) or “King of the Sky” (Thaen yuu faa) necessarily imply a critique of the King of Thailand?

I discussed these questions with a couple of Bank’s friends in Khon Kaen. Each of us had slightly different readings, but we all agreed that it is a matter of interpretation that goes beyond the scope of criminal law. To illustrate, let me try answering “no” to all the questions above:

- No. There is no reference to “the monarchy” at all. The idea that there’s nothing natural about social inequality will remain relevant even when no monarchies remain in this world.

- No. Queer-minded humans may be any class of persons who don’t believe in equality before the law—both in the sense of equality under the law and in the sense of equality prior to any man-made law.

- No. Phya Thaen is the highest being in Isan Lao cosmology, roughly equivalent to God. What does the King of Thailand have to do with that? Is he bigger than the sky, mightier than God (yai khap faa)?

But you never know. There is no shortage of Thais who seek to cover the sky with one hand. On April 4, the Office of the Council of State’s Facebook page published a now-deleted infographic about the lese majeste law that grossly overextended its interpretative reach: “to insinuate” (priap proey), “to engage in satire,” and “to show disrespect” all amount to a violation. The infographic also asserted that claims to “lack of intent” had no weight, since malicious intent can be presumed from the act.

What about the act of looking up at the open sky, and musing on why there are so many unbridgeable gaps in society? The song’s refrain takes me back to another observation I heard a week earlier. After the exodus of peaceful protesters from Old Bangkok across Pinklao Bridge to escape trigger-happy riot police and thugs, I joined a small group walking back across the bridge to find our way home. On the bridge, a 70-year-old uncle from my home province glanced at the empty road, saying: “the road’s so wide—still we aren’t allowed to go on it” (thanon tang kwaang, kaw yang mai hai rao pai). Like the refrain, this observation resonates with meaning. Note too, the absence of a subject who refuses to share to road.

Why do these critical remarks about inequality lack a clear target? Bank’s original lyrics, unlike my English translation, don’t mention a “you” (jao). Being subjected to the oppressive air in the courtroom revealed to me that this kind of omission isn’t necessarily an act of self-censorship. Rather, omission can highlight how oppression is felt as pervasive yet unaccounted for, like air that suffocates.

In the hands of this Morlam, mundane observations and heavenly cosmology reveal rather than mystify. The folk song advances “un-Thai” ideas like human rights and economic redistribution, showing how commonsensical they can be.

One of the striking things about Bank’s work is how it conjoins entertainment and political education. When I listened to Lam ploen faa bor kan nyang khue waa haang kan for the first time, I was struck not by the lyrics but by the breezy way Bank sang them. Styled as a lam ploen, “pleasant song,” the piece makes a daring call to powers-that-be, as if it’s the most natural thing to do.

This subtle and resourceful quality of morlam, a friend of Bank’s told me, is why the Thai establishment fears Bank. Following in a long line of rebellious Morlams in Thai history, this millennial has proven that the millenarians’ egalitarian impulse remains alive and kicking.

Thus the challenge to the agonizing question “how much of himself is Morlam Bank offering up?” might be “can the egalitarian impulse that Bank has renewed through his art of morlam really die?”

Pictured: The face of morlam Bank screened on a paper kite, the night of March 20, 2021 (Image supplied by the author).

* * *

On April 9, after exactly two months in prison, Bank was released on bail and court conditions. He was the only one released that day, even though Somyot (#4) and Pai (#7) agreed to similar silencing conditions. Penguin and Rung’s hunger strike would continue for several more weeks until their release under the same conditions.

“Deadened” (taai daan) was the word Bank used to describe his feeling to the press outside the prison gates. Since then he has kept a low-profile. Public political statements by him or about him, including the publication of this essay, have been put on hold.

When I think about the silencing of Bank today, it is impossible not to think of Khamsing Sri-nawk (pen name Lao Khamhom), author of the Thai short story collection Faa bor kan (yes, also “Heaven Doesn’t Divide”), first published in 1958. Khamsing faced persecution for his literary works during the Red Scare of the Sarit regime, and wrote only a few books in the decades following Faa bor kan. Khamsing once compared his dwindling output to a faded romance: “It’s like you used to love this woman and would write letters to her all the time. But now the love is gone, and you no longer feel like writing to her.”

Yet, Faa bor kan continues to garner new fans and generate new critical responses. The book remains a testament to the enduring inequality under this sky, as well as to the possibility of creating equally enduring works of art under these conditions.

Bank told me that, save for a few ballads, he wasn’t able to write much this time in prison. I told him not to worry, since he already wrote so many pieces the first time around I wouldn’t be able to finish translating them any time soon. And even if Bank sticks with “apolitical” entertainment for the rest of his life, I am certain his art of morlam will once again find some way, deliberately or not, to overflow whatever strictures imposed. With the Morlam silenced, morlam resounds. His words, including in “silent” form, will go on to haunt other heads. His silences, too.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss