Part 1: A Seminar on “Thoughts of Kassim Ahmad”

The long, one might say lifelong, agony of Kassim Ahmad continues.

The latest episode in this saga of official harassment is now being played out in the courts.

The continuing 2014 episode: A Seminar in Putrajaya

Earlier this year, in February, Kassim Ahmad gave a talk, presumably at the invitation of Tun Dr. Mahathir himself, at the former prime minister’s Perdana Leadership Foundation headquarters at the national capital, Putrajaya.

The subject was a restatement of Kassim Ahmad’s well-known and long-standing views: about the primacy of the Quran itself to Islam; its direct accessibility to intelligent interpretation by reasonable Muslims of good faith; the mystification and distortion of the original Quranic message that Kassim (not uniquely) holds has taken place as a result of the often arcane, esoteric, sophistic and exclusionary interpretive efforts of the officially credentialled ulama –– and the consequent emergence within Islam of a powerful clerical elite and a doctrinally dubious, even illicit, clericalism.

Dubious and illicit, since the emergence of such a caste or “estate” of religious “experts” asserting a monopoly upon legitimate exegetic entitlement and religious truth arguably puts in doubt, even question, the core Islamic principle that there may and shall be no intermediaries between the believer and the Almighty.

Reports of the Perdana Foundation event appeared in the usual media outlets, including Malaysiakini, The Malaysian Insider and The Malay Mail Online.

A powerful response was not long in coming.

Officers of the federal religious department JAKIM (or Jabatan Kemajuan Islam Malaysia, a division within the Prime Minister’s Department, but not one that is conspicuous for its support for Prime Minister Najib’s “Movement of Global Moderates” initiative!) came to Kassim’s home in Kulim, Kedah in the dark of night, demanded and then made a forcible entry, arrested Kassim and removed him to their own jurisdiction, very far from Kulim, to interrogate him.

That they did, to a physically frail man of over 80 years of age, at considerable length.

Kassim, through his lawyers, is contesting their action.

On a variety of grounds.

These involve questions of the relation of state and federal jurisdiction, of the relation between the Common Law or civil and Shari’ah law traditions and their implementing bureaucratic authorities and instrumentalities, and also fundamental constitutional questions about the rights of individuals.

The courts, so far, have been prepared to treat questions of disputed jurisdiction. But so long at those matters are being sorted out, they are reluctant to open up and enter into deliberating upon the basic constitutional questions: the wider question of the fundamental rights of citizens in matters of belief, conscience and speech.

As the matter is now publicly understood, Kassim Ahmad faces at least three charges. These in effect involve causing offence to Islam, of questioning and opposing the status and standing of the ulama as duly authorised officials of Islam and as exclusive and definitive arbiters of correct Islamic practice, and also –– a little mysteriously –– what is referred to as one further indictment that remains sealed and must for the meantime remain confidential (though one assumes that its nature and terms must be known to the accused himself, Kassim Ahmad).

What can this be and mean?

Only one thing, it would appear. Or so one must surmise.

Namely, that a further charge has been prepared against Kassim, on the basis of the specific and substantive views that he expressed.

A charge either of making himself an apostate (murtad) or else of placing himself outside the bounds of proper belief, of kufr –– of an explicit adherence to and the knowing promotion of infidel beliefs and convictions.

Those who have prepared this further, still undisclosed charge are in that case probably acting upon the view that it is improper to say or suggest that another Muslim is in effect a kafir (heretic) or murtad (apostate) before such a charge is proven. So it must remain confidential.

This shows some decent sensibility.

But there is more to the matter than that.

Holding that already prepared charge in readiness, in reserve, would also have the effect of exerting enormous pressure upon the accused to accept some sort of “plea bargain”: to agree, on the two open counts, to a charge of offending Islam and the ulama as a state-organised collective entity –– as the bureaucratic custodians of “correctly understood Islam”, or simply “religious officialdom” –– in order to avoid being formally declared and branded as a heretic and apostate.

With others such a stratagem might work.

But not, I expect, with Kassim.

Frail though he may be physically, he is a man of enormous will and determination. He is stubborn, meaning by nature and character unyielding in upholding his own pride and dignity.

It is hard to see Kassim ever consenting to such a deal.

Meanwhile, as the matter proceeds through the courts, all mention of Kassim’s lecture earlier this year has been removed and expunged from the Perdana Leadership Foundation’s elegant official website.

Who is Kassim Ahmad?

Hardly anybody these days knows, or any more remembers, who Kassim Ahmad is.

Press reports on his official travails and difficulties always repeat the same lazy typification: bekas aktvis sosial, “former social activist”.

The man is much more than that, and deserves to be known and acknowledged, even honoured, for who he is and what he has done.

Born in 1933, Kassim Ahmad began his “public” life and career as a student activist at the old University of Malaya in Singapore, where in the 1950s he was one of the young “progressives” who called for a revision and opening up of the existing, derivatively colonial curriculum.

But he was not merely a campus activist.

He was also a scholar of prodigious talent and ability.

For example, when I was working in the late 1960s and early 1970s on the evolution of Kelantan political society in the nineteenth century, I found much that was of value to me in Kassim Ahmad’s MA thesis. This was a critical annotated edition of the Sha’er Musoh Kelantan [= “Epic of the Kelantan War”] that Kassim had submitted in 1961.

That was the beginning.

From there Kassim went on to become a lecturer in Malay Studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London.

But always the activist, the engaged thinker, and as a man rooted in the culture of the Alam Melayu or wider Malay world and its evolving political dynamics, Kassim found the idea of the expansion of Malaysia into the new Federation of Malaysia questionable –– and said so, emphatically.

He was soon branded as a Sukarno-ist, an apologist for Indonesian Konfrontasi, or “Confrontation” against Malaysia, and identified as an enemy to the nation and a threat to national security.

He returned to Malaysia, and though the pool of talented and qualified people was not large, he was considered unacceptable for a university appointment.

For while he was found work, by old friends, as a research officer at the Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, where he produced an elegant, meticulously edited and prepared edition of the Hikayat Hang Tuah.

But for him, literature was not just dead words on a page.

He became one of the central protagonists in one of the great literary debates and cultural polemics of the 1960s: over the question whether Hang Tuah, who, out of conventional loyalty, had been ready to kill his friend Hang Jebat because of the ill-founded envy of the ruler, was still to be treated as a model for emulation by modern, progressive young Malays –– or whether Hang Jebat, with his doomed personal loyalty to his best friend, was more worthy of admiration.

The question became the subject at the time of a learned article in the famous Dutch academic journal, the so-called Bijdragen voor de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde [Transactions in Linguistic, Geographical and Ethnographic Knowledge], produced by the Royal Dutch Institute in Leiden. Under the heading of “The Rise and Fall of a National Hero”, the noted Professor P. E. de Josselin de Jong traced the eclipse, on a course charted by Kassim Ahmad, of Hang Tuah’s reputation in those important debates and polemics.

During a large part of the 1960s and 1970s Kassim pursued a modest livelihood as a school-teacher. But his life, as a man of ideas and commitment and action, was centred upon, and within, the old Parti Raykat or (at times) Parti Sosialis Rakyat, with all its internal controversies about doctrine and ideology, direction and strategy.

That remained the case until, in the great round-up of those deemed a radical threat to the nation after the death of Tun Razak, Kassim was detained under the notorious ISA: Internal Security Act.

Of the many who were detained at the time, few, it seems, took it harder, and found the experience more corrosive of their former confidence, than Kassim. Others were, by nature, more flexible, and so could accommodate better to the humiliating conditions. Not Kassim.

He was too proud to be flexible, and too much the master of his own mind and thinking to be able to pretend that he thought what he did not. He has written of those years in his prison memoir Universiti Kedua/A Second University (both Malay and English-language editions, 1983).

During his detention, Kassim became seriously interested in Islam, Islamic thought and intellectual history, Islamic philosophy, and the explicit and also implied or “immanent” social and cultural theory offered by Islam. He wrote a book on the subject: Teori Sosial Moden Islam, Fajar Bakti, 1984.

This was followed, in a course of developments that is traced below in the essay entitled “Milestones”, by two more specific works in this area: Hadis: Satu Penilaian Semula [= Hadith: A Revaluation], 1986 and Hadis: Jawapan Kepada Pengkritik [= Hadith: A Reply to My Critics], 1992.

Kassim’s detention came to an end with the accession of Dr. Mahathir to the prime ministership.

This was no special favour. Few people these days recall the great optimism, enthusiasm and sense of reforming zeal, and the hope of opening up long-blocked possibilities, that accompanied Dr. Mahathir’s assumption of national leadership.

As part of that “new liberating spirit”, Dr. Mahathir released a very large number of ISA political detainees.

But, among them, it might be said –– in a way that will later become clear in “Milestones” –– that there was a special affinity or congruence between the ideas of Dr. Mahathir and Kassim Ahmad.

Both were strong believers in the idea that Muslims, all Muslims who could do so, had the obligation to educate themselves, both generally and in matters of religion.

That all who did so had the right, the ability and also the duty –– once they had begun to educate and emancipate themselves as Muslims –– to decide many religious matters for themselves. By thinking things through for themselves.

Both were, in that sense, de facto “protestants” in a religious tradition that had not experienced a fully developed protestant challenge or “reformation”.

Both believe in the sovereignty of the intellect and conscience of the educated Muslim of good faith.

Both felt and said that Muslims of this radically individualistic intellectual orientation did not really need the ulama, or any self-protecting clerical “estate”, to tell them what or how to think or to resolve all difficult religious questions for them.

Both took the view that, once the ulama as a group had come into being and consolidated their own position, their interests and outlook often became those of the exclusive social group of which they were members –– and not necessarily the proper or correct or best-advised outlook for Islam as a whole, for Muslims generally.

Both became, in that sense, in some measure “anti-clericalist Muslims”: Muslims for whom the ulama, with their often casuistic reasoning and ways, were not always, or perhaps ever, the best exemplars or defenders of Islam. Nor even, for the both of them, were the ulama always right. Often they were not. And their fallibility had to be kept in kind, both men held, especially when the ulama called for near automatic deference and unquestioning assent.

That said, Dr. Mahathir had a very full, varied and richly diverse life, especially after 1981. In a world of power.

The powerless Kassim’s life after his release from detention in 1981 was more bounded and closely focused, largely upon his religious ideas.

He promoted those ideas, sometimes with Dr. Mahathir’s encouragement and support, and was also made to suffer for them.

So, while one may liken both Dr. Mahathir and Kassim Ahmad to Islamic “protestants”, their fates have been very different.

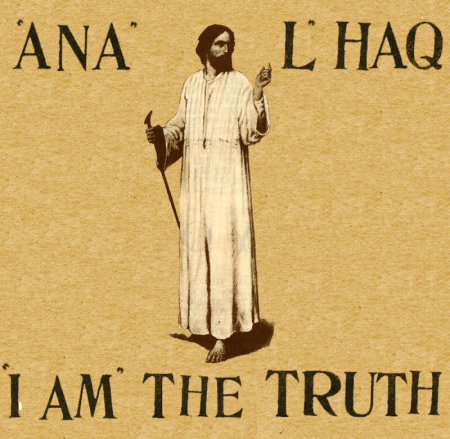

In his own passionate “witnessing” of his beliefs, in his public struggle to promote, uphold and defend them, Kassim has been turned into a modern-day Malaysian al-Hallaj.

The great thinker al-Hallaj was hounded for years and in the end (in 922CE/309AH) gruesomely put to death for his commitment to the idea “ana al-haqq”: meaning, not as the punitive conservatives interpret it “I am the truth” or God incarnate (in some quasi-Christian fashion), but rather, “the truth is within me, it is to be found within my own thinking self, my own free mind”.

Let us hope that Kassim’s public career concludes not cruelly, as did al-Hallaj’s, but with the belated and overdue bestowal of some generous part of the recognition and honour that he is owed, that his contributions have amply earned for him.

To be continued in Part 2.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss