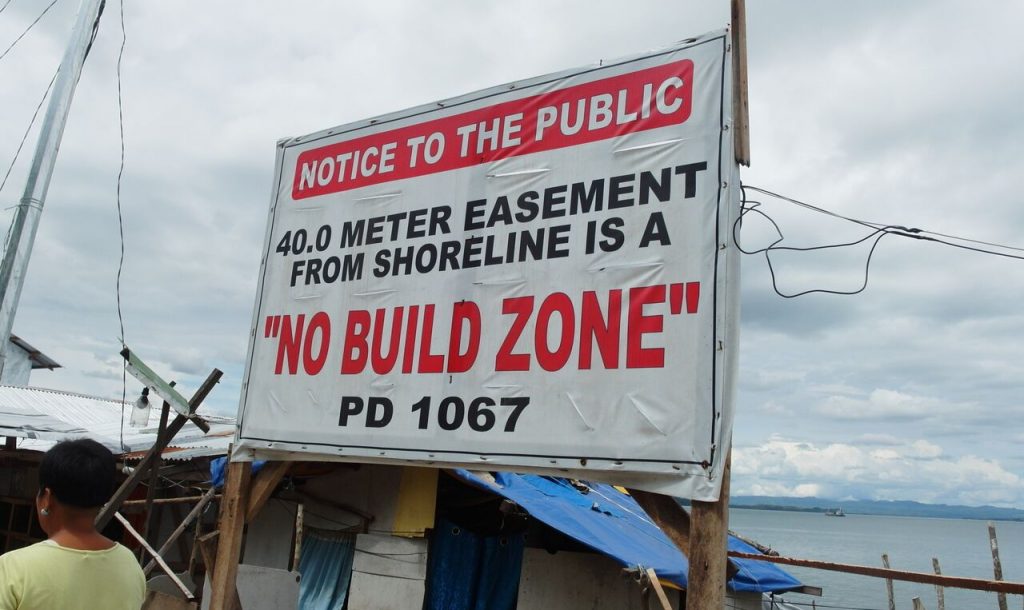

Typhoon Haiyan demonstrated the vulnerability of communities living along the coast. After a seven-metre storm surge swept through the homes of families who have lived along the shore for years, the government decided to strictly implement its “no build zone” policy and prohibited communities from living along the shore as a safety measure.

Consequently, many survivors were left with hardly a choice but to relocate to the resettlement sites provided by the government (some were provided by development organisations).

These resettlement sites have made families less vulnerable to tsunamis and storm surges but they have also sentenced them to a more precarious life.

Few viable livelihood opportunities were created in Tacloban North—the new township where communities now live. Many felt that the significance of their livelihood was overlooked, as if an hour and a half transit ride downtown, the centre of Tacloban’s economic life, is not such a big ask for communities who are already time-poor and have limited resources.

The Dumpsite behind GMA Kapuso Village, one of the resettlement sites in Tacloban North. (Photo: Ladylyn Mangada)

This oversight upset many disaster survivors. My respondents could not recall government or NGO workers conducting a serious investigation about how to match the skills of communities to plausible livelihood programs that can be launched in areas where they now live.

As a result, most resettled survivors had to resort to commuting to their old villages to find work. Others who could not afford to commute are forced to build makeshift living quarters in the coast so they can work in the city and bring their earnings to their families in the resettlement sites. Disaster survivors had to rely on their own resources to put their lives back together.

Survivors living in the resettlement sites in Tacloban North wait in line to fill up their containers with water from the government’s delivery trucks. (Photo: Ladylyn Mangada)

“We have a new concrete house but our stomach is empty” is a common comment one can hear from families relocated to the northern part of the city.

Build back better has been the mantra of the Philippines after Haiyan. For many, however, this promise remains elusive, as housing programs, it seems, served to only make things worse.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss