On Monday 26 August Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo announced that the nation’s capital would be relocated to the province of East Kalimantan. The move relates to the national government and its administration, including parliament, ministries, supporting offices and relevant military, police, social and economic institutions. Provincial governor Isran Noor has conveyed East Kalimantan’s readiness to receive the new capital, while people in the province expressed expectations of a rise in employment possibilities and a diversification of the economy. Yet they also fear a decrease in the quality of their living conditions and an increase in the influence of the central government on local affairs.

On the whole, around 200,000 civil servants will be expected to move. When counting their families, new infrastructure such as hotels, restaurants, shops and all the jobs that come with these, the new capital will likely become the largest city of the province rather quickly. Balikpapan and Samarinda, the two main cities, both have around 850,000 inhabitants. In the weeks preceding the announcement, it had already become clear that the Indonesian provinces on the island of Borneo would be selected as the new location, but the specific spot still surprised many. The location, which encompasses land in the districts of Penajam Paser Utara and Kutai Kartanegara, is rather out-of-the-way and undeveloped. It sits roughly behind and around the coastal city of Balikpapan—East Kalimantan’s centre of business and commerce—and is presently in use by plantation companies catering to the plywood and building materials industry.

It is by now quite likely that the capital is going to be moved. Whether that is really necessary, however, and, if so, whether East Kalimantan is the best location, are still being questioned. Also, little attention is being given to the manner in which the intended move fits in with regional politics and desires, on which people in East Kalimantan have quite diverse views.

Is it necessary to move the capital, and is it likely to happen?

The plan to move the capital elsewhere has been raised periodically throughout Indonesia’s post-independence history. President Soekarno intended the new city of Palangkaraya in Central Kalimantan as a new centre of government that would be ‘Indonesia-oriented’: smack bang in the centre of the map of Indonesia and an independent achievement free from the colonial roots on which Jakarta as a capital was built.

Soekarno’s plans were thwarted by the 1965 coup, but his successor Suharto took up the idea in the 1980s and suggested moving the national administration to Jonggol in Bogor. This was waylaid by investors starting a land rush to that area and starting wild land speculation, which put a stop to concrete plans under Suharto’s rule. Following Reformasi, the plan reappeared under Widodo’s predecessor Yudhoyono, who emphasised Jakarta’s overpopulation, congestion, pollution and vulnerability to natural disasters. Rather than suggesting a new location, he thus made the issue one of ‘moving away from’ rather than ‘moving to’.

Jakarta is sinking due to the unchecked extraction of water from aquifers below the city, which causes increasing vulnerability both to flash floods caused by heavy rainfall in Java’s mountainous interior and to flooding by seawater. Furthermore, Java’s location along the Sunda megathrust puts Jakarta at risk of increasing earthquakes. Over the past year, West Java has been hit by some ten earthquakes. Most of these ranged between magnitudes of 4.5 and 5.2, but early August saw an earthquake of magnitude 6.9 that rocked Jakarta. The damage was limited, but the quake shocked many Jakartans.

The sheer size of the urban agglomeration of ‘Jabodetabek’ (Jakarta-Bogor-Depok-Tanggerang-Bekasi), with some 30 million inhabitants and near-legendary traffic jams, is illustrative of the size of the infrastructural issues the city faces. Yet Jakarta is taking these challenges on: its partially underground mass rapid transport (MRT) system recently began operating in March of this year and is designed to withstand flooding and earthquakes. The city has also begun construction of a mega-dam along its seashore to protect from coastal flooding. Critics point out in the media that moving the national government may not do much for Jakarta as such, given that only around 3% of the population would relocate. They also point out that the move is a mega-operation that requires much more substantial planning than has been carried out so far; that the costs might well be gargantuan; and that removing the government could detach the political elite from the daily realities of life of the common people.

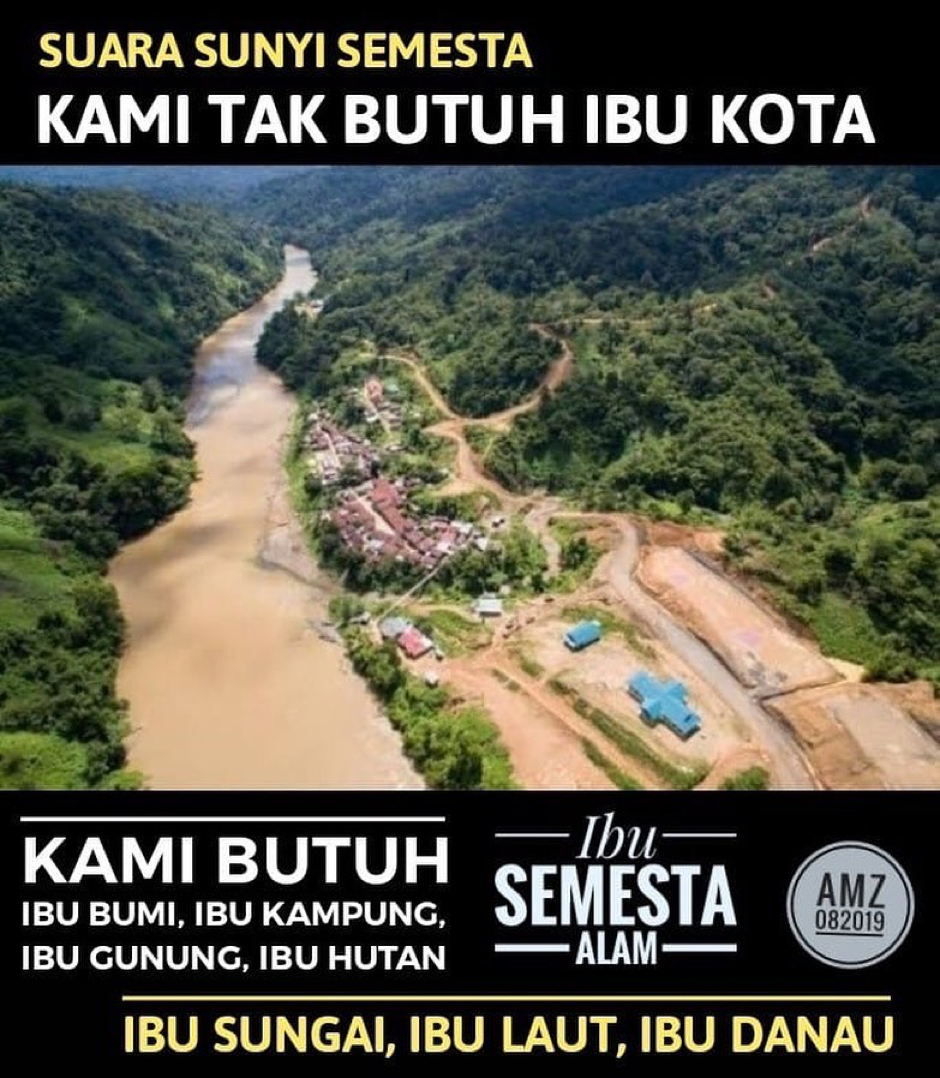

A protest poster against the new capital making the rounds on Facebook and Pinterest. It reads “We do not need the capital (literally: mother town). We need mother earth, mother village, mother mountain, mother forest, mother river, mother sea, mother lake. Mother universe.”

Yet the move also has its proponents. While in Jakarta during Jokowi’s announcement, I discussed the issue with academics at universities and with several civil servants. Although all were impressed with the size and complexity of the operation, these Jakartans saw that the quality of life in Jakarta is not improving and that the current approaches to its most fundamental problems are insufficient to offer substantial solutions. Moving the capital now, a staff member of the National Planning Agency pointed out, is preferable over a future move necessitated by a disaster. Costs might be high, but, if all goes well, it will largely be paid for by third parties rather than by taxpayers, and will be more manageable now than when incurred during an emergency move. Crucially, the national government already owns the required land in East Kalimantan. NGOs and activists in Kalimantan I asked about the move point out that rather than becoming isolated and out of touch the nation’s political elite will finally be made to take notice of the lives of ordinary people outside of Java.

The launch of the plan just after Widodo’s re-election is strategically well-timed. If work goes as intended, the new capital will begin operating by 2024, just at the end of Widodo’s second term in office. Importantly, the national parliament still has to ratify the move, but it seems unlikely that the project would have been announced without sufficient political support. Alternatively, although not likely, Widodo could choose to move his project ahead without parliamentary fiat by using a Presidential Decree.

Is East Kalimantan the best location?

The choice of East Kalimantan as the capital’s new location has various advantages. The province is – and has been for decades – a migration destination. The resulting population is diverse and includes communities of most Indonesian ethnic groups. Although there are sizeable minorities, no single ethnic group is a majority by itself. Locally people joke that their province is ‘Indonesia in miniature’, while ethnic and religious relations are largely peaceful. The province is also resource-rich and prosperous. It is home to large coal, oil, and gas reserves and related industries, as well as to extensive palm oil and wood plantations. Importantly, the province has no volcanoes and is decidedly less flood- and earthquake-vulnerable than Jakarta. Perhaps most importantly, the province is sparsely populated and offers ample space for construction and infrastructure on its vast plantation and (reclaimed) mining land. Also, it sits quite close to the centre of the map of Indonesia, the symbolism of which drove Soekarno’s choice for Palangkaraya, but which is emphasised by the present regime as logistically fair to all parts of the country.

Out of sight, out of mind? Political accountability and Indonesia’s new capital plan

What happens when civil society, the media, and policymakers are based in different cities?

The new capital is envisioned to encompass some 200,000 hectares (slightly below a third the size of Jakarta’s designated capital territory) and the nominated location consists of well over that amount in state-owned forest land. One of the present users, plywood producer PT ITCI Kartika Utama, holds by itself a concession of 180,000 hectares. Such concessions can, however, be retracted relatively easily as they confer a right to use of state land but not ownership. This means that obtaining the required land is likely to be considerably easier than when private land would have to be appropriated. That is not to say that this may not also be necessary: as the likelihood of East Kalimantan as a location has increased, investors have speculated by buying land banks around Balikpapan and Samarinda. Even though they missed the main location in doing so, this land is likely to become sought after if expansion will take place. The chosen location around and behind Balikpapan means that the new capital can be serviced by the existing good-quality airport and harbour facilities, and can be easily connected to the newly-finished coastal toll road connecting Balikpapan and the provincial capital of Samarinda.

Opposing voices mainly emphasise environmental issues. Greenpeace Indonesia warns that if the development of the new capital neglects environmental measures from its construction onwards, it could easily end up facing issues of pollution and flooding as well. Nearby coal mining may cause floods and droughts in the new capital (as it already does in Samarinda), and the location is in an area of Borneo that is seasonally plagued by the smoke and ashes of forest fires further away.

Furthermore, the proposed location borders (and partly overlaps with) several protected forest areas. While the largest of these—Bukit Soeharto—is in parts already severely degraded through illegal settlement, logging and even mining, the part of this forest area that will border the new capital is in a relatively good condition. The Minister for Planning emphasises that protected forest areas will be spared, yet the question must be asked whether this can be maintained if they directly border the national capital.

For Balikpapan, the status of the Sungai Wain protected forest is a serious point of concern. Located between the city and the new capital, Sungai Wain functions as a watershed for the city and reduces the risk and impact of floods in the rainy season. If the plantations that presently cover the proposed location of the new capital are replaced by concrete and asphalt, this might well increase the frequency and severity of floods for lower-lying Balikpapan.

Local politics

In East Kalimantan, the selection of the location has been interpreted by proponents as a conciliatory move on the part of the central government. Opponents argue that on the contrary, the move might well turn out to be a means to strengthen the central government’s grip on the province. For almost a decade, East Kalimantan has been recalcitrant towards some of the central government’s policies. In 2011, during the Yudhoyono presidency, East Kalimantan’s provincial government drafted a multi-year development plan that emphasised green development through plantations and sought to limit mining, as this industry is a major source of pollution. The central government overruled this plan and sought to expand the mining industry as the main pillar of the local economy.

A consortium of activists, citizens and scholars—backed by the provincial government—reacted by requesting the Constitutional Court to review the law regulating the division of revenues from natural resource extraction. They argued that while the central government obtained a major share of these revenues, the province had to cope with deforestation, pollution of water sources and other environmental consequences for which the law did not provide. This, the consortium argued, went against the rights of Indonesian citizens as set out in the national constitution. They sought a greater share of the revenues for the provincial government to offset the negative impacts and requested the Constitutional Court to review the constitutionality of the law.

When the Court did not find the law to be unconstitutional and rejected the request, a group of students and activists (again backed by the provincial government) approached members of the national parliament to put forward a proposal to give East Kalimantan special autonomy (otonomi khusus), a status otherwise only enjoyed by the provinces of Aceh and Papua. Special autonomy would allow the province greater shares in revenues as well. While the parliamentarians refused, the provincial government reached an agreement with the central government over a new division of revenues more profitable to the province. Profits were limited, however, by the 2016 collapse of the global coal market.

Yet the green politics championed in provincial planning remain alive as well. Informed by Samarinda’s experience of flooding and water pollution due to open-pit mining surrounding the city, Balikpapan has staunchly refused mining within its city limits. The city sits in part on seams of high-quality coal, but its government has prioritised a higher quality of urban life over additional funds. This has not been without result: the city is top-ranked in Indonesia’s most liveable cities index and is, despite its extensive oil refineries and gas industry, of surprising ecological quality. President Widodo is promising for the new capital to be smart, beautiful and green.

Although the project has only just been announced, its local impact is substantial. Very few details are known as yet regarding the specifics of the plan to construct the new capital and relocate staff and government within the given time frame, but the citizens of Balikpapan and East Kalimantan are already divided. The provincial government emphasises the boost in jobs, the diversification of the economy away from natural resource extraction, and the honour and prestige granted to East Kalimantan. But critical citizens and NGOs worry that a new city of a million inhabitants will be disastrous for their environment, push up land, food and housing prices and attract even more migrants looking for opportunities. They fear that despite Widodo’s intentions, the capital will become a conglomerate-driven business enterprise that will undermine Balikpapan’s environmental policies as well as be simply detrimental to the quality of life due to its sheer size. Among the civil servants required to move, for instance, quite a few are considering to leave their families in Jakarta due to existing facilities there. Their trips to be with their families will multiply the number of flights at the already busy Balikpapan airport, while their travelling to and fro might cause traffic jams as the airport is in the city. While many agree that its selection as the site of the new capital is an honour of sorts, the effect of the central government descending on the province might, it is feared by critics, constitute a take-over in practice.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss