On 29 June, Indonesia’s Special Detachment 88 (Detasemen Khusus 88) arrested Para Wijayanto, the current head of the transnational Islamist rebel group Jema’ah Islamiyah (JI)—now called Neo-JI by Indonesian security officials—in Bekasi, West Java. On the one hand, this arrest is cause for celebration. The search for Wijayanto that started in 2008 ended before he was able to conduct any attack. On the other hand, this arrest has highlighted the uncomfortable reality that JI has successfully survived after a series of debilitating assassinations and arrests of its leaders between 2007–09.

Though Neo-JI lacks military capabilities, its strength—like that of JI in the past—lies in its patient and opportunistic establishment of grassroots support. To address such a threat, Indonesia must look beyond hard-approach counter-terrorism operations and better invest in sustainable soft-approach measures that target the social roots of Neo-JI. Concerning characteristics shared by Neo-JI and its predecessor remind of three important facts about terrorism in Indonesia. First, the threat represented by terrorist groups does not merely lie in their capacity to conduct violence. Second, professional terrorist groups are not short-sighted but strategic, patient and calculate long-term gains. Last, terrorism is a protean enemy.

Neo-JI’s rebranding

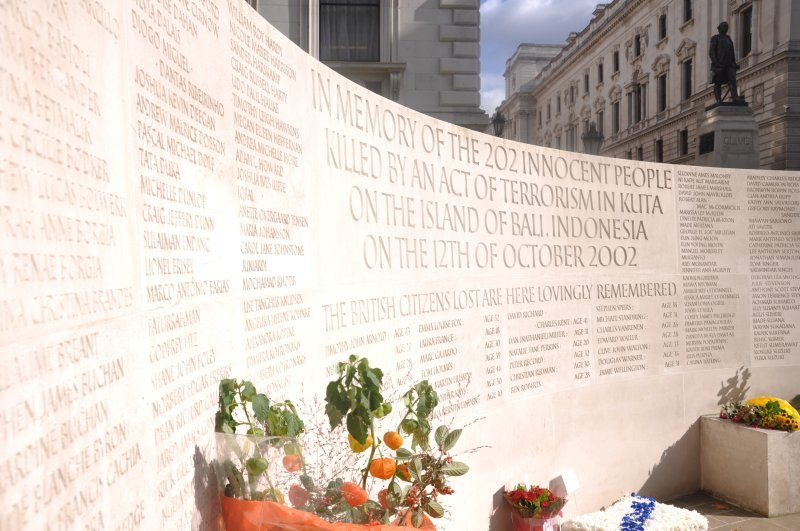

Neo-JI is a salafi-jihadist group that aims to safeguard a purist version of Islam and establish a caliphate in Indonesia. The group is, in a way, a continuation of JI which began developing across Southeast Asia in 1993 and conducting violence in Indonesia in 1999. The lethality of JI’s violence peaked in 2002 with the Bali Bombings, which resulted in 202 deaths and 300 injured. In the aftermath, it continued to conduct well-known attacks, such as the 2004 Australian Embassy bombing and the 2009 JW Marriot and Ritz Carlton bombing, though with declining severity. By 2010, a majority of JI’s senior leaders—such as emir Abu Bakar Ba’asyir and emergency emir Zarkasih, as well as skilled operatives such as JI’s lead expert bomb maker Azahari bin Husin—had been either arrested or killed, effectively neutralising the group’s violent activities.

The creation of a new JI began in 2008 due to two imperatives. First was the realisation that violence had triggered significant backlash against the group. Internal debate over the cost of violence began as early as 2002. Many members argued that the Bali Bombings cost the group more than it gained, due to the loss of popular support from the deaths of Muslims and the increased counter-terrorism effort against JI by the Indonesian government. This debate peaked in 2007 after Operation Tanah Runtuh, a police raid that was performed in response to JI’s beheading of two Christian girls in late 2005. This raid ultimately led to the death and capture of 77 JI members, debilitating the group’s network.

The second imperative was the dwindling number of operatives that JI can rely on to conduct attacks. A large part of this erosion was caused by internal splintering within JI, such as Noordin M. Top’s recruitment of JI’s smartest young militants to his own Tanzim Qaedat al-Jihad in 2004, and Abu Bakar Ba’asyir’s similar recruitment of key JI commanders and well-known ulamas to his organization, Jema’ah Ansharut Tauhid, in 2009. In the face of increasingly effective counter-terrorism operations, by the late 2000s the group was struggling to conduct attacks.

Seeing these realities, Neo-JI refocused its efforts on three fronts. First, they refocussed efforts from violent attacks to dakwah (preaching) and education campaigns. Whereas previously terrorist attacks had become JI’s primary method, members now believe that violence can and should be abandoned if it undermines JI’s main goal to build popular grassroots support through dakwah. One of the first dakwah initiatives that Neo-JI implemented was the creation of the Indonesian Ulama Da’wa Council (Majelis Dakwah Ulama Indonesia, or MDUI). The organisation was tasked with sending preachers to remote villages outside of Java. By 2011, it had sent preachers to 65 regions outside of Java including areas such as Papua, East Nusa Tenggara, Maumere and Bontang.

A 2017 report by the Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict showed that by the end of 2013, Neo-JI had established an active education division network of 24 coordinators that reports to seven heads of section spread across Western Indonesia (five head of section) and Eastern Indonesia (two head of section). The report noted that 95% of these coordinators were consistent in conducting regular meetings throughout the year—regular monthly meetings in the Western region and regular tri-monthly meetings in the Eastern region. In total, the division had spent Rp 403 million on its programs and reached an audience of 2,950 university students.

The second change that Neo-JI made was to refocus its efforts from developing a clandestine network structure to developing its legal above-ground economic and social organisations. Neo-JI’s economic endeavours are relatively successful, as noted by their ownership of palm oil plantations in Sumatra and Kalimantan along with clove and cacao fields in Southeast Sulawesi. Income from these sources is reportedly sufficient to generously fund programs and officers. Reports in 2017 noted that senior Neo-JI officers were given monthly salaries between Rp 500,000–2 million. More recently, police noted these numbers to be between Rp 10–15 million.

Additionally, Neo-JI was also successful (for a time) in developing above-ground humanitarian organisations. One organisation was the Hilal Ahmar Society Indonesia (HASI), an organisation that was revitalized in the wake of the Syrian crisis to distribute aid towards victims. Between 2012 and 2013, HASI conducted 60 public discussions and amassed Rp 130 million for Syria. Part of those donations were sent to jihadi groups such as Jabhah al-Nusroh and Ahrar Al Syam. Although HASI was banned in 2015, other humanitarian organisations linked to Neo-JI, such as Lembaga Kemanusiaan One Care, still operate to this day.

The third change Neo-JI adopted was redesigning its military structure to be more streamlined and focussed on training. Neo-JI’s focus on dakwah and education does not necessarily indicate that the group has fully revoked violence, as leaders believe that the group is now merely in a state of i’dad (preparation). This preparation began in 2010 when leaders approved the establishment of a clandestine military wing, strictly separated from its above-ground structures. This military wing only had one regional division, as opposed to four during JI’s reign, and used a closed cell structure where face-to-face interaction was largely replaced by courier communication.

Though military training ran relatively unencumbered, it was reported that there was a crucial lack of access to weaponry that would have provided members experience and technical knowledge to conduct attacks. Aside from the difficulty of accessing black market products, the group also failed to sustainably develop home-made firearm factories (a Klaten-based factory that modified airsoft guns to fire real bullets was found by police in 2014). In 2013, Neo-JI improved its training by sending six members to Syria where they were exposed to important weapons training and real jihadi operations (for example, border patrol between Syria and Turkey).

Slow and steady: implementing the JI playbook

At face value, Neo-JI does not seem to be much of a threat. It seems to have learned that violence is detrimental and has refocussed its efforts on peaceful dakwah, education and socio-economic endeavours. Its small attempts to prepare for violence, either by training operatives or amassing weapons, have either had low impact or were easily foiled. Neo-JI’s perceived low threat level is further emphasised when the organisation is compared to pro-ISIS groups such as Jema’ah Ansharut Daulah (JAD), which has consistently conducted high-profile attacks such as the Sarinah bombing in 2016, the Kampung Melayu bombing in 2017 and the Surabaya triple church bombing in 2018.

As a result, as Bilveer Singh noted in 2018, ‘Neo-JI has effectively been given a green light to operate freely’. Some Indonesian security agencies even believe that there are benefits in using the group to counter and balance pro-ISIS groups. This perception is a mistake.

Despite its stark differences to the violent JI of 2002–07, Neo-JI exhibits clear signs of being a threat which deeply mirror JI’s development playbook during their 1993–99 phase. This mirroring is evident on three levels: strategic priorities, structure formation and operational decision-making.

Neo-JI’s strategic prioritising of amassing popular grassroots support over the use of violence strongly mirrors Abdullah Sungkar and Abu Bakar Ba’asyir’s motives for splitting from Darul Islam (DI) to create JI. In the early 1990s, when Sungkar and Ba’asyir were still key members of DI, the two had several disputes with DI’s leader, Ajengan Masduki. The most significant dispute surrounded the issue of the jema’ah (community). In a 2002 interview, Abu Rusydan explained that Sungkar and Masduki had heated debates regarding the starting point of the movement. The former believed that the Islamic State is already established and simply occupied by the Indonesian government, while the latter believed that the Islamic State is not yet established as there is no popular support for the concept in Indonesian society.

This debate significantly influenced the strategic priorities of both parties. Where Masduki wanted to focus on attaining territory, Sungkar wanted to prioritise amassing support from the jema’ah. As a result, Sungkar and Ba’asyir separated from DI to prioritise the movement’s engagement with society. As Rusydan notes, ‘[JI’s] starting point would now be with the jema’ah’ and that they would focus on two fields: ‘education and dakwah – Sungkar’s passions since the 1970’s’. This belief that popular grassroots support should be square one for the movement translated into a multitude of efforts to establish madrassah across Southeast Asia. Before JI began to conduct its attacks in 2000, Sungkar and Ba’asyir had already established madrassah such as Al-Mukmin and Lukmanul Hakiem as dakwah and recruitment nerve centres.

Neo-JI’s focus on developing an above-ground economic and social structure also mirrors Sungkar and Ba’asyir’s development of JI’s network structure between 1993–99. It is true that JI sustained its operations between 2002–07 through illicit donations from Al Qaeda and illegal activities such as robberies. But between 1993–99, JI’s economic durability also came from legal above-ground economic sources. Hambali had a significant palm oil company exporting to Afghanistan, while another member was noted to have a large chemicals company. The profits of these companies were taxed 10% by JI and used for operational purposes.

In 1998, JI also established a humanitarian organisation under the name of the Crisis Management Action Committee (Komite Aksi Penanggulangan Akibat Krisis, or KOMPAK). Despite being better known for its military training operations by 2003, KOMPAK was originally designated to provide relief programs to communities in conflict areas such as Kalimantan, Maluku and Central Sulawesi. Through multiple branches in big Javanese cities such as Semarang, Surabaya, and Solo, KOMPAK collected donations that would be used to fund JI’s firearms procurement and weapons training.

Similar to Neo-JI today, between 1993–99 JI’s leadership also decided to not engage in any form of violence—not because they did not condone violence, but because leaders astutely assessed there was no opportunity for them to do so. During this phase, JI still invested heavily in military training and preparations. These efforts were relatively successful due to the existence of accessible conflict zones and safe havens (for example, Mindanao) that made weapons readily available and allowed operatives to train freely. Between the late 1990s to 2000, JI sent a total of 170 operatives to train in the Moro Islamic Liberation Front’s Camp Hudaibiyah in Mindanao, and a total of 20 operatives to become experts in Al Qaeda’s Camp Al Faruq along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border.

The JI leadership’s decision to halt their abstention from violence in 2000 was incentivised by opportunities created by Reformasi. This included a surge in unaddressed and undirected Muslim grievance due to years of oppression by Soeharto, the weakening role of Indonesia’s military and police on a regional level, and the rupture of inter-religious sectarian conflict in Poso and Ambon. By the late 1990s, JI leaders were still uncertain of the group’s main target, with members disputing between the ‘far enemy’ and the ‘near enemy’. But the availability of these opportunities quickly shifted JI’s priorities and led to the beginning of JI’s violent phase in Indonesia.

Countering terrorism in Indonesia

Despite its stark attempt to rebrand itself, Neo-JI is no different from the old JI. In fact, its priorities, structure and decision-making processes strictly mirror JI during its 1993–99 phase. Indonesia should not be lulled by the group’s current lack of military capabilities and peaceful activities comparative to other pro-ISIS groups. Neo-JI’s strength and threat, similar to that of JI in the past, lies in its long-term vision of establishing grassroots support and its ability to patiently and astutely wait for opportunities.

The concerning characteristics shared by Neo-JI and JI inform us of three important facts about terrorism in Indonesia. First, the threat represented by terrorist groups does not merely lie in their capacity to conduct violence. A professional terrorist organisation is one that also supports itself through a myriad of legal business and popular institutions. The state should acknowledge that hard-approach measures against terrorist operatives and leaders are simply not sufficient to eliminate the threat.

Distinguishing piety and fundamentalism in Indonesian Muslims

Survey data show no evidence of a link between piety and intolerance, let alone violence.

Second, terrorist groups are not short-sighted. JI waited 7 years to conduct its first attack, and Neo-JI has patiently waited more than 10 years to amass popular support. Professional terrorist groups are strategic, patient and calculate long-term gains. The state should aim to devise more sustainable soft-approach (for example, deradicalisation and counter-radicalisation) measures. Soft-approaches measures are not new to Indonesia’s counter-terrorism repertoire. Between 2002–09, Indonesia implemented an array of soft-approach initiatives including providing economic assistance to terrorist convicts’ families, and disseminating delegitimisation narratives against radical interpretation of Islam.

These measures have not been successful not because they lack in quantity, but because they are often short-sighted. These programs rarely share findings and lessons between one another, which prevents the development of more well-informed deradicalisation programs. Additionally, transferral of knowledge from civil society organisations conducting those programs to prison guards once the program finishes is rare, which prevents guards from following up on whatever progress was made during the program.

The third lesson is that terrorism is a protean enemy. It changes and acts according to the opportunities available. When violence is not possible, terrorists prepare. When violence is possible, they use it. As a result, state counter-terrorism operations should also focus their efforts on addressing opportunities for violence. This includes meaningfully addressing domestic Muslim grievances, increasing participation in regional counter-terrorism operations to prevent the creation of nearby safe-havens (for example, Marawi). It also means managing the growing pool of potentially skilled operatives as terrorist convicts finish serving their sentence and individuals from Syria continue to return.

Indonesia should not be lulled by Neo-JI’s seemingly peaceful development and rely solely on hard-approach operations against its leaders. If Neo-JI is anything like its predecessor—and as shown above, there is cause to believe it is—the state should invest large efforts in sustainable soft-approach measures and operations that prevent opportunities for violence.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss