Years since the killing of prominent human rights defenders and political commentators; the judiciaries of Indonesia, Cambodia, and the Philippines still have failed to take any concrete actions to deliver justice to the case that is acceptable to the public. These prominent individuals put their lives on the line for social justice, yet no justice has been found for their expression.

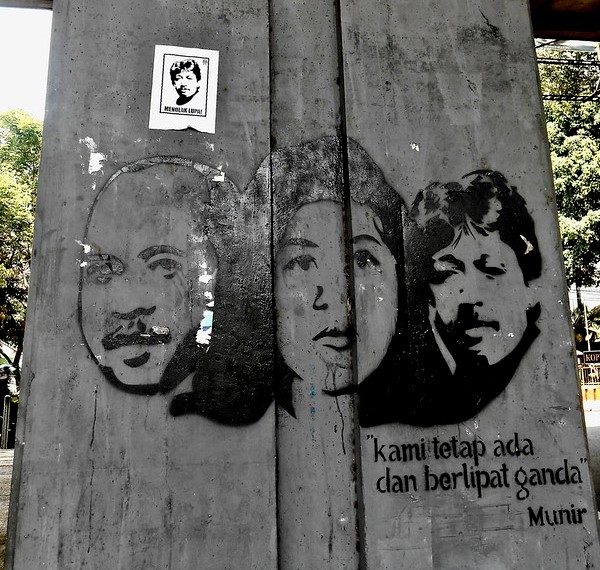

On 7 September 2004, Munir Said Thalib, a well-known human rights activist, was poisoned with arsenic and found dead on a flight from Jakarta to Amsterdam operated by state-owned airline Garuda Indonesia. Kem Ley, one of Cambodia’s best-known political commentators, was drinking his morning coffee at a petrol station café in Phnom Penh when a man walked in and opened fire, killing him instantly in July 2016. Zara Alvarez, former education director of the human rights alliance Karapatan, died on the spot after being shot six times on Monday evening, August 17 of 2020, as she was heading home after buying food for dinner.

Before his assassination, Munir had been repeatedly targeted because of his courageous criticisms of human rights abuses and exposure of corruption. One day before he was killed, Kem Ley had spoken publicly about the NGO Global Witness report, Hostile Takeover, which exposed the close ties between Cambodian’s ruling family and private sector. Zara Alvarez was the 13th member of her organisation—working on human rights protection—killed since mid-2016 when Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte came to power.

While these countries have a number of regulations that protect freedom of expression, they also have in recent years approved many legislations that act as double-edged swords enabling broad interpretations and may be applied to further constrict offline and online civic space and exacerbate restrictions on freedom of expression in these countries.

Since 2020, Indonesia has passed a new Criminal Code with various provisions potentially used to violate free speech. For example, Article 219 criminalises insults to the president and vice president. In addition to the existing Information and Electronic Transactions (ITE) Law, the State Flag and Symbol Law, and Pornography Law that could be used to prosecute individuals attempting to voice dissent, criticise or merely state an observation. The country also issued Ministerial Regulation 5, known as MR5, compels digital service providers to register with the government, or face being blocked and fined. According to the law, digital services and platforms must also provide the government access to their systems and remove content within 24 hours of being notified by the government. Due to its broad scope, the law is highly likely to imperil freedom of expression if used excessively.

Similarly, in 2018, the one-party state government of Cambodia passed amendments to five articles of the Cambodian constitution, one of which required Cambodian citizens to defend the motherland. The revision of the Penal Code, which includes a lese majeste provision, means that politically-motivated prosecutions at the expense of free speech in Cambodia are now both lawful and constitutional. In the digital space, in the same year, Cambodia issued Proclamation No. 170 on publication controls of website and social media processing via internet in the Kingdom of Cambodia. According to Clause 2, “the Prakas (Proclamation) aims at obstructing and preventing all public and news content sharing or written messages, audios, photos, videos, and/or other means intended to create turmoil leading to undermine national defence, national security, relation with other countries, national economy, public order, discrimination, and national culture and tradition.”

In addition to the proclamation, in February 2021, Cambodia unveiled Sub-Decree No. 23 on the Establishment of National Internet Gateway (NIG), a bill to establish a national internet gateway that can control online communications, similar to the Great Firewall of China. When fully implemented, it will enable coordinated government surveillance

In the Philippines, the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020 was enacted in July, a bill that allows for warrantless arrests and longer detentions without charge and could be directed at anyone criticising the president or the government. Together with the government’s long-running counter-insurgency program and its widespread use by the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELAC), it legalises red-tagging campaigns conducted by the government.

Charles J. Dunlap Jr.’s concept of lawfare explains how authoritarian governments and allied parties weaponise the law and legal institutions to weaken or eliminate any resistance from opposition parties and other nonstate entities. The inability of the court system to guarantee that legislation does not unduly infringe on fundamental freedoms, as well as the lack of legal rationale, leaves Southeast Asian governments plenty of opportunities to legalise repression.

While the right to freedom of expression is not absolute, and international human rights law—such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights or ICCPR—allows certain permissible limitations, many states enacted and adopted laws to prima facie fulfill the “provided by law” requirement, although these are fundamentally contrary to the principles of international human rights law and fail to meet the principle of “legal certainty” of international law.

The Johannesburg Principles on National Security, Freedom of Expression, and Access to Information provide legal principles and conditions for any limitation proscribed by law, and demand laws be accessible, unambiguous, drawn narrowly and with precision to enable individuals to foresee whether a particular action is unlawful. However, repressive legislation in Indonesia, Cambodia, and the Philippines employ broad terms that grant authorities significant discretion to restrict expression and provide limited guidance.

In a similar vein, the Siracusa Principles on the Limitation and Derogation Provisions in the ICCPR provide interpretive principles relating public order and national security—the most popular so-called “legitimate aims” used to restrict free speech in Southeast Asia. According to the principles, public order is defined as the sum of rule which ensures the peaceful and effective functioning of society, whereas national security is only an acceptable justification for limiting rights when the political or territorial integrity of the nation is threatened. While public order must be limited to specific situations where restrictions to rights would be demonstrably warranted, national security applies only to the interest of the whole nation, excluding restrictions in the sole interest of a government, regime, or power.

In 2011, the UN Human Rights Committee stated that using such laws to suppress or withhold information of legitimate public interest that does not jeopardise national security is incompatible with the permissible limitation. To prosecute journalists, researchers, environmental activists, human rights defenders, or others for disseminating such information will never be compatible with the permissible limitation. Moreover, all public figures, including those exercising the highest political authority such as heads of state and government, are legitimately subject to criticism and political opposition. Criticism of institutions, such as the army or the administration, should not be prohibited; further, the UN Human Rights Council (2016) reaffirmed that political or government interest is not synonymous with national security or public order.

Indonesia, Cambodia and the Philippines have not provided justice to victims of extrajudicial killings who were exercising their right to freedom of expression. Worse, they have enacted and implemented vague laws that could be used to prosecute individuals who are attempting to voice dissent, criticise or merely state an observation. These new forms of legalising repression, clearly diverge from international human rights standards and international laws.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss