There are few places in Singapore that conjure feelings of dissonance. In a republic tightly controlled by the state, urban design—along with the feelings they evoke for inhabitants—remain largely contoured by the nation’s ruling elites. Most palpably, where state legitimacy rests upon economic stability, state leaders in Singapore have worked to minimise overt articulations of class disparity in everyday spaces of the city.

Perhaps most emblematic of this endeavour is Singapore’s public housing project. Housing over 80% of the local population, these residential neighbourhoods have served to integrate residents of diverse socio-economic (as well as race) groups—an undertaking that has been touted as one of the world’s most successful. By consequence, not only has the Singapore state maintained for most residents, through the public housing experience, a sensibility of “middle class” homogeneity, but it has also averted spatialised forms of poverty, including racialised variants thereof, that have emerged elsewhere around the world.

State urban planning, calibrated as may be, of course cannot erase the realities of class inequality in Singapore. Over the decade to 2020, national Gini coefficient scores have remained above the 0.45 level (although averaging out above the 0.4 mark following government transfers and taxes). A 2020 report published by Credit Suisse presented ghastlier revelations, indicating that the richest 1% of Singapore residents now own more than a third of total national wealth.

Yet, careful urban planning—of public housing especially, but also the separation of the wealthiest in gated districts far from where most Singaporeans reside—has worked to mask the appearance of these disparities in the everyday. Where the state controls space, so then does space become instrumental in shaping (perceptions of) social reality: out of sight, out of mind. Nonetheless, even against this shrewd contouring of urban space, cracks persist. With tenacity (and perhaps some luck) one may find, roaming around the island, corners that will betray everyday urban illusions of Singapore’s invisibilised social divide.

(Dis)enchanting abodes by Upper Changi North

The rapid economic development of Singapore from the late 1970s would occasion new affluence, and with it new material appetites, for the country’s residents. Among these aspirations was the coveted, more luxurious, private residential home—in particular, the condominium apartment (today still one of the key symbols of material achievement in the republic).

In the beginning, many early condominium projects in Singapore appeared in the prime locations of the city centre, notably Horizon Towers, Arcadia Gardens, and Orchard Bel-Air to name a few. Yet as Singapore’s economy continued to expand, property developers began to seek out new districts in the city’s more affordable suburban corners. One company in particular, Tripartite Developers Pte Ltd (comprising Hong Leong Holdings, City Developers, and TID), would turn their attention to the area known today as Upper Changi North.

Seeking new investment opportunities on the back of the burgeoning economy, this conglomerate would acquire over three million square feet of land in the region, specifically, the swathe that triangulates today’s Upper Changi Road, Flora Road, and Flora Drive. Thereafter, Tripartite began a massive construction undertaking over the newly acquired land, erecting numerous private condominium homes that would soon that enchant prospective residents from all over Singapore.

Chinese elites have looked to Singapore as a model throughout much of the reform era, but have failed to understand what made the city-state tick.

How Deng and his heirs misunderstood Singapore

Nearby the upcoming complex, on an adjacent plot of land, more private housing projects abound. Another of Hong Leong’s making, one will encounter here older condominium estates, like Avila and Estella Gardens, as well as other landed terrace homes that cluster around neighbouring Mariam Way. Walking through the labyrinths of private housing (and watching the expensive cars cruising around), few would doubt that the area remains an abode to more affluent segments of Singapore society, even if the area cannot entirely compare to the more expensive residences of the city centre.

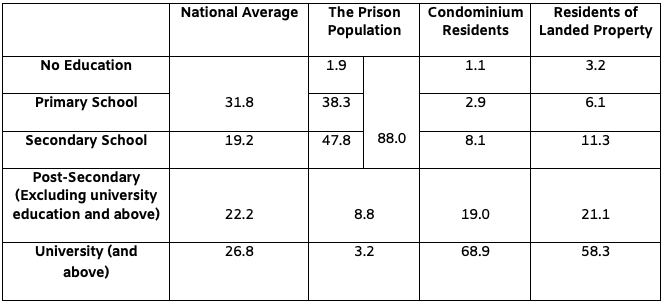

Strolling then up Flora Road (or the parallel Flora Drive), one would expect, passing by one condominium complex after another, what looks like an endless stretch of well-decorated private homes. Yet, with little warning, a grim reality soon appears. At the junction of Upper Changi Road, across the maze of condominium complexes, one will encounter instead Singapore’s largest and most prominent carceral institution—Changi Prison. And it is here, at the intersections between Upper Changi and Flora, where the fractures in the state’s urban illusions are laid bare.

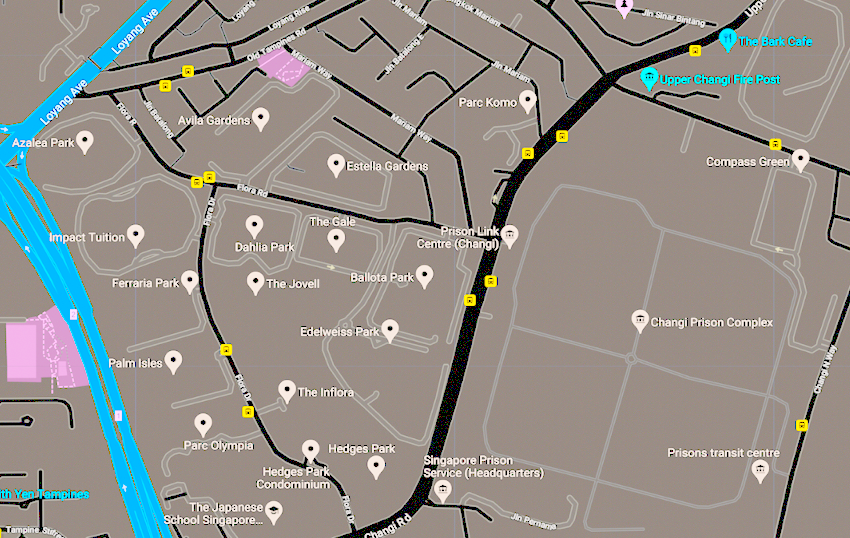

A map of Upper Changi Road. To the left are the swathes of private, condominium complexes, and to the right, the Changi Prison Complex. Source: Google Maps)

What ideas are evoked by this uncanny scene of luxurious homes set in close proximity to the national prison?

First, unexpecting visual similitude. Walking along Upper Changi Road, one is bound to notice peculiar architectural similarities between the two types of development. There, strikingly prominent are enclosures that encircle the prison and condos, all physical constructions designed to prohibit access to the otherwise unauthorised: the prison with its large gates, high walls, and barbed-wire fences, and the condominium with smaller gates and shorter walls, but also innovative barriers such as artfully designed fencing and well-maintained bushes.

Also ubiquitous is surveillance. Standing at both the main entrances of the prison and condominium are various security personnel, along with closed-circuit cameras operating without end in and around the respective premises. With little surprise too, one will find guards conducting frequent patrols within both areas (although these personnel, admittedly, are, more difficult to peek at from outside the prison compound).

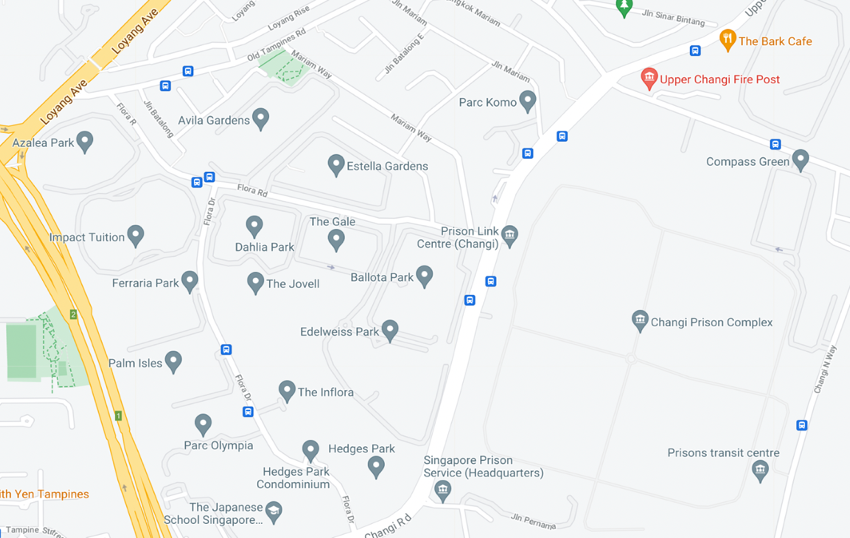

Of course, should both developments—the prison and condominium—appear to mirror one another in some way, they are rarely if ever taken for the same. As one local property listings site bemoans of the Hong Leong project, “[having] a prison in your background could be a permanent eyesore”—but only as it tries to cajole readers to consider “why it’s really okay to live next to Changi Prison” anyway. After all, the page suggests, “cell blocks [are] well tucked away from public sight” and that “many such areas [of the prison] look nothing like a prison at all” (emphasis added). Coincidentally, advertorial materials for Tripartite’s “The Jovell”, in a most convenient manner, disappears the entirety of the Changi Prison Complex.

Here, a palpable sentiment remains: condos and prisons are conceived as having little to do with another, and any likely connection between one and the other ought to be minimised, if not done away altogether. Thus, where the prison stands as a site of blight, its proximity to an object of status, the condominium, serves only to tarnish the latter’s appeal (and predictably too, its market value).

An online publicity flyer for The Jovell with amenities in the Upper Changi Area marked out. Absent here is the Changi Prison Complex. (Source: The Jovell official website)

The side entrance to one of the many condos along Flora Drive, walled and gated with signs warning non-residents against entry. (Photo: author)

Yet, for all these attempts at severing any relation between the condominium and prison, the two developments remain surprisingly bound with one another—a relation that is mediated only by Singapore’s economic trajectory.

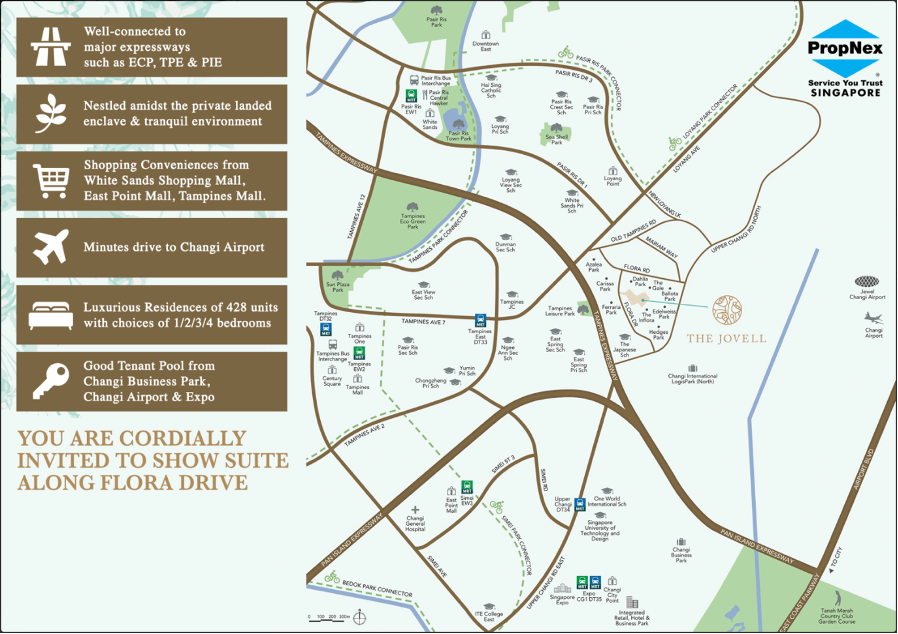

For one, it will come to the surprise of nobody that condominium residents in the city often constitute better-educated, high-salaried professionals. Official surveys indicate that over 87% of condominium residents hold post-secondary qualifications, with 68.9% having had acquired university degrees. In addition, more than 75% of condominium households have monthly incomes above S$8,000, with 53.3% that exceed the S$15,000 income threshold (residents of landed property, meanwhile, tend to be even wealthier).

By contrast, prison demographics offer a far grimmer story. In conversations with social workers and other prison volunteers, I am told of a persistent spectre that follows those serve who prison terms—poverty and economic precarity. However, absent publicly available data on the financial status of Singapore’s incarcerated, ascertaining the veracity of these anecdotes become difficult. Despite this hurdle, education attainment statistics found in official prison reports can nonetheless offer clues regarding the reality of economic precarity among prison occupants.

Quite perturbingly, yearly records from 2006 to the present reveal that most of Singapore’s prison population, an overwhelming 88%, do not hold education beyond the secondary level, with only 3.2% having completed university education. Contrast this with national records that indicate close to 50% of Singapore’s residents holding some form of post-secondary qualifications, of which over half have university qualification. No doubt, considering that education remains a key determinant for employment and upward mobility, and acutely so in certificate-conscious Singapore, prison demographic data suggest limited socioeconomic mobility for large segments of the incarcerated.

It bears mentioning here too that carceral cases in Singapore rarely involve white-collar or violent crimes. Instead, as official reports show, over 70% percent of the prison population have been criminalised for drug-related offences, with recent parliamentary discussions revealing that four-fifths of the Singapore’s prison population today have experienced prior imprisonment, the majority of whom being repeat drug offenders.

Education Demography in Singapore by Highest Qualification Attained, 2006–2020 (%)

Source: Singapore Department of Statistics (https://tablebuilder.singstat.gov.sg/table/TS/M850581)

Equally concerning is the place of race in Singapore’s prison demography. In a private conversation from 2019, one prison counsellor informed me that Malays comprised approximately 55% of the total prison population—a disturbing statistic, given that Malays constitute a mere 15% of Singapore’s total citizenry. Recently, state authorities in Singapore have confirmed the disproportionate representation of race minorities in prison occupancy all while hesitating to release data on the breakdown of the prison statistical by race.

Against this backdrop, one cannot help walking along Upper Changi but consider the dissonances of race that triangulate residential developments in Singapore. Notably, if intrusive state intervention in Singapore’s public housing project has resulted in some uniformity in the racial distribution of its residents—at least in accordance with national demographics—private housing and Changi Prison, exempt from these regulatory forces, make most apparent the race-related differences that underlie the Singapore social fabric.

Most perturbingly, where Malays are overwhelmingly represented in the prison population, Malays remain almost absent from condominiums and other residences of private property. Singapore’s 2020 census indicated that Malays constitute only 2.1% and 1.6% of residents in condominiums and landed property respectively, far below their levels in public housing; the equivalent figures for Indians were 8.9% and 6.9%, and for Chinese 83.6% and 87.3%.

Standing then on Upper Changi Road, between the Changi Prison and Tripartite–Hong Leong real estate enterprise, is most bewildering. Where one side of the street is characterised by the wealthier and well-educated, the other is ascribed to the poorer, less socio-economically mobile, the majority of whom constitute a racial minority group.

How ought one reckon here with long-held, national narratives of meritocracy and equality vis-à-vis this perturbing, topographical reality? Does Changi Prison constitute a de facto poverty ghetto and minority-race enclave of modern Singapore? What are the conditions under which such (spatialised) inequality have materialised, and most unsettlingly, what has come to mediate between those who are offered “rewards” (the condominium, as many designate it to be), and more disturbingly, “punishment” (a prison sentence)?

Blocks C and D of the Changi Prison compound, situated along Upper Changi Road, encircled by fencing and signs that warn against intrusions. (Photo: author)

There are not clear answers to these questions, especially given the paucity of attention accorded to (and available records on) Singapore’s penal landscape. Yet scholars of carcerality—the politics and ideology that underpin practices of incarceration—offer coordinates to navigating this puzzle. Most notably, in their seminal The Rich Get Richer and the Poor Get Prison, Jeffrey Reiman and Paul Leighton identify economic failings, namely poverty, as a principal source of crime. Economic pressures, the authors argue, confront the poor “with needs that they are less able than well-off people to satisfy legally” while “offer[ing] them fewer rewards for staying straight”.

By this reading, Reiman and Leighton call to our attention political economy—specifically that which enables wealth accumulation alongside disenfranchising exclusion and poverty—that has led many of the poor and resource-deprived to wind up in the penal system. Here, by centring poverty and class inequality—even as affairs of criminality may exceed economic status (e.g., sexual harassment and related violations remain no doubt entwined with regimes of gender)—Reiman and Leighton offer clues as to why so many occupants of Changi Prison comprise the economically precarious, the majority of whom possess limited educational attainment, much less upward professional mobility.

Furthermore, given the historical and persistent socioeconomic disenfranchisement of the Malay community in Singapore, it becomes less surprising now why prison occupants are overrepresented by Malays. Historically, minority Malays in Singapore have fared, in comparison with other race groups, with poorer outcomes across various socioeconomic domains, including academic achievement and median income.

This disparity, as Lily Zubaidah Rahim dissects, remains consequent of state policies, including urban resettlement, electoral engineering, and anti-welfarism, that have economically disenfranchised Singaporeans (of all race groups), but in disproportionate numbers, Malays. Recently too, national surveys have called attention to a doubling of the number of Malays in rental flat homes, housing provided to low-income families in Singapore. Thus it would appear, against this backdrop, that the racialisation of prison occupants likely pertains less to matters of race per se, but rather to national concerns of class and economic inequality.

It bears mentioning here that sociological accounts of Singapore also have documented heightened police surveillance in spaces inhabited by the poor. Looking to rental neighbourhood specifically—the homes occupied by many of Singapore’s most economically precarious—Teo You Yen calls attention to “the presence of police, both literally and metaphorically” as a persistent feature. Notably, Teo notes of the frequent police patrols as well as various posters and signages in common areas of rental flats that warn low-income residents against illegal conduct.

Elsewhere, scholars have underlined also heightened policing in other places occupied by the economically precarious. These include Geylang, commonly referred to as Singapore’s main red-light district from where many vulnerable sex workers work, as well as Little India, a popular spot for the city’s many low-waged migrant workers. On the case of migrant workers in particular, one ethnographic study reveals, by the admission of one police officer, heightened policing of migrant worker residences. (Specifically, the junior police officer explains, “when we go for patrols, we are taught to be extra alert and careful around the [migrant worker] dormitories and hostels. We become more suspicious of their behaviour. There’s always a risk that they might commit a crime or turn violent”).

As these examples show, class disparity, whether racialised along the lines of local minority race groups or non-citizen migrant workers, remains intricately intertwined with surveillance, policing, and incarceration. So it would appear, given the prevailing (but questionable) attempts by the state to securitise spaces inhabited the poor, that ruling elites remain attuned to the social perils that accompany poverty and inequality—even as everyday urban design might effect the invisibilisation of this reality.

Of space, affect, and consciousness

Should one become so habituated to familiar illusions of the city, it is a journey to Upper Changi that may perhaps elicit new forms of affect and thought. Here at this juncture, between prison blocks and condominiums, the dissonant realities of wealth and poverty, largesse and deprivation, the upwardly mobile and those left behind, collapse into a singular topography. Neither spatially removed from nor blurred communally into one another, both developments evince themselves, despite the veneers of difference and incompatibility, as sharing a boundedly intimate relationship. And in a most disorienting display, these spaces (along with those housed within them) remain only outcomes, divergent as they may be, as tethered to an unequally bifurcating economic system.

Thus, far more than literal space, Upper Changi offers then an avenue for re-evaluating the Singapore story. Situated physically between two juxtaposed versions of Singapore, one becomes compelled here to rethink the familiar narratives espoused through everyday navigations of the city, especially those of the public housing neighbourhood; and most specifically, the prevailing challenges of (racialised) class disparity and its relationship with criminalisation, surveillance, and carcerality in Singapore.

In light of this, to traverse through the area entails then interruption, not merely of concerns around the spatial fabrications of the modern city, but more urgently, local consciousness surrounding the invisibilised socioeconomic realities of this beloved nation–home.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss