After years of debate, protest, and delay, the Indonesian parliament passed a new criminal code (Undang Undang Kitab Hukum Pidana, or KUHP) that gives the state new tools to punish a wide range of ideological, moral and political offences. International attention has focused on those passages of the law that ban sex outside of marriage. But the KUHP’s real power lies in provisions that threaten political dissent with prison sentences and have the potential to muzzle public debate about the purview of the state in citizens’ private and political lives. Here we examine the divergent interests that coalesced to pass the most regressive provisions of the new criminal code, and consider their implications for Indonesian democracy.

A compromise between two illiberal agendas

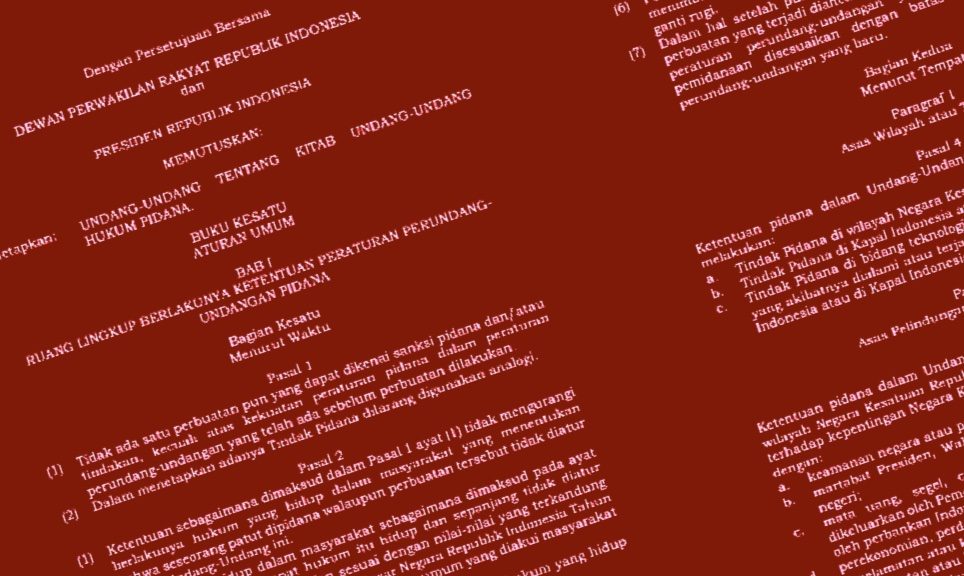

Indonesia’s old criminal code was inherited from the Dutch colonial state and included a range of outdated provisions. The effort to revise the law began in the 1980s under the New Order regime but went nowhere after several fully formed drafts were discarded. After the democratic transition in 1998, attempts to revamp the code became entangled in ideological battles between nationalist parliamentary factions who sought to purge Dutch influence, and religious conservatives who saw the revisions as an opportunity to push for a greater role for the state in regulating public morality.

The new KUHP, passed unanimously by all parties on 6 December, represents a compromise between these two factions. Nationalists, led by PDI–P, drove provisions that not only retain existing criminal charges for expressions of support for “Communist/Marxist-Leninist” thought, but also ban expression of “ideas that contradict Pancasila”, the state’s pluralist ideology. Legal activists in Indonesia believe these provisions smack of the Sukarno-era Anti-Subversion Law, a vaguely-worded statute that was used to great effect by the Suharto regime to repress and intimidate dissidents.

At the same time, the new law, which bans all sexual relations outside of marriage, also represents a major victory for Islamist groups. The Islamist PKS party has long championed efforts to regulate public morality through its proposed Family Resilience bill. The draft of this law was brought up for discussion in the parliament several times but failed to garner broader support because of its extreme provisions — which among other things regulated sleeping arrangements of siblings within households and compelled family members to report homosexual relatives to state authorities. The new KUHP, which designates sex outside of marriage and cohabitation between unmarried couples as jailable offences, if reported by close relatives, incorporates watered-down versions of passages in the Family Resilience bill.

Why did a compromise become possible when the governing coalition is ostensibly dominated by religiously “pluralist” parties that could have mustered the votes to pass the new code without accommodating Islamist demands?

Since Indonesia’s deeply polarising presidential elections in 2019, Jokowi’s government has imposed a “repressive pluralist” agenda to counter political opposition by banning Islamist groups and purging state agencies of religiously conservative civil servants. But neither Jokowi nor his allies in parliament can afford to isolate conservative Muslim groups more broadly, especially as the 2024 elections approach. This consideration became even more important when the morality provisions in the KUHP bill gained endorsement from mainstream Islamic organisations, including Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) and Muhammadiyah, who are also under pressure to guard their conservative flanks in the wake of the 212 movement’s bringing divergent views about the role of Islam in public life to a head. This is evident from NU and Muhammadiyah’s conservative stance on recent issues concerning morality, especially their opposition to using a consent-based definition of rape in the Sexual Violence Law passed earlier in 2022. Placating religious conservatives with policy concessions in the social domain has thus become an expedient way of containing the potential fallout from subduing their opposition in the political arena.

Apart from striking these compromises, the new KUHP also serves the goals of political elites across ideological divides of curbing the role of civil society in the policy-making process. Over the past few years the government has been subject to mounting public criticism for passing legislation that is seen as protecting interests of powerful oligarchs and reducing accountability. Changes to legislation governing the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) in 2019, which effectively dismantled the popular anti-graft body, prompted the largest pro-democracy protests since the student mobilisations of the late 1990s that toppled the New Order regime. In 2020, the rushed passage of the Omnibus Law on Jobs Creation—which reduced labour protections, dismantled environmental safeguards and expedited forcible land acquisition by the government, with the aim of attracting foreign investment—also galvanised widespread protests.

The new KUHP makes these expressions of opposition high-risk. Citizens can now be jailed for up to three years for making comments about the president and vice president that the latter deem derogatory. It also contains provisions for punishing anyone who circulates derogatory material about government institutions more broadly, including government ministries, the courts or the parliament. When it was passed into law in a sparsely-attended plenary session of parliament, the PKS representative staged a walk-out to protest these “insult” provisions, and its fellow opposition party Partai Demokrat offered a perfunctory warning of the risks to free speech, perhaps to save face with their constituents. But both had already formally endorsed the final version of the law in the committee that drafted it.

Government reassurances fall flat

In the face of widespread criticism of the KUHP, government officials have been quick to defend the new criminal code by urging the public to celebrate the fact that Indonesia has finally managed to shake off its colonial legacy. These platitudes offer cold comfort to the journalists and activists who are most likely to be targeted by the law and have repeatedly pointed out that it actually retains and repurposes the most repressive aspects of the original version inherited from the Dutch.

For example, provisions for punishing insult to the president that were part of the old KUHP were annulled by the Constitutional Court in 2006, which ruled that general defamation laws were sufficient to protect holders of public office from personal attacks. The new law reinserts these provisions and expands their scope to cover other state institutions, with two alterations. First, it makes them complaint-based offences, meaning they can only be applied if the “insulted party” reports them. Second, it stipulates that criticisms that are made in the public interest will be exempt from prosecution. Lawmakers claim that these limitations offer a safeguard against potential misuse of the law, which they argue is not meant to forbid dissent but reasonably regulate it.

Such arguments presume that powerholders will exercise restraint. But in reality several litigious ministers within Jokowi’s cabinet already have a track record of suing critics. The new KUHP’s provisions on insulting the government give such actors a greater incentive to go after activists, who will now bear the additional burden of proving their innocence for the obvious reason that there is no clear or explicitly defined difference between an ‘insult’ and a critique of the state or heads of government.

Another reason activists don’t trust the government line is that these revisions follow years of relentless state harassment of activists using existing regulations, especially the anti-“defamation” provisions of the Electronic Transactions Law (UU ITE) and the authorities’ increasingly unrestrained use of force against demonstrators, as seen during the student protests of 2019–2020. The chilling effects of this trend can be seen in the fact that while the protests against the previous attempt to pass a new KUHP in 2019 were massive, this time the streets are relatively empty. Additional provisions in the new code that increase criminal penalties for organising protests without prior notice to authorities are likely to reinforce these trends.

Regardless of whether and how these rules are applied, legal experts in Indonesia have pointed out that they have no place in a democracy. Indonesia is not the only country that has laws to protect heads of state from wilful defamation, but these regulations are generally rooted in a history of monarchy, where sovereigns are considered sanctified entities. When applied in a representative democracy like Indonesia, these provisions have the potential to transform the role of government officials from public servants, who are subject to criticism from the citizens who elect them, to entitled rulers who ought not be defied.

When it comes to the law’s morality provisions, proponents claim that they codify Indonesia’s shared moral values and increasing the role of state authorities in enforcing them will prevent vigilantes from taking the law into their own hands. The evidence suggests the opposite might be the outcome: we know that in Aceh province — which enforces the strictest public morality regulations in the country, punishing fornication, adultery and homosexuality with public canning — the incidence of mob violence to punish moral offences is three times higher than the Indonesian average.

Indonesia's parliament has approved Jokowi's decree on mass organisations. Here's why the law threatens the freedoms of all Indonesians.

Jokowi forges a tool of repression

Finally, proponents argue that dissatisfied citizens are free to critique and even challenge the law. Indeed, the government has developed a template response to public opposition to its legislative agenda: “just take your complaint to the Constitutional Court”. This phrase is routinely dropped by ministers, party leaders, and the president himself.

But even this avenue for recourse is closing fast. Over the past two years, the government has led a systematic effort to undermine judicial oversight of the legislative process. In September 2020, the parliament voted to extend the tenure of Constitutional Court judges from 5 to 15 years, which was criticised by legal experts as a bid to incentivise a favourable ruling on the judicial review of the Omnibus Law. Following the Court’s conditional annulment of that legislation, however, the government is now mounting a more direct attack on judicial independence. In November 2022, lawmakers removed Justice Aswanto from the Constitutional Court for voting to strike down the Omnibus Law, and replaced him with a new judge who they claim would defend the parliament’s interests.

A nail in the coffin?

The new KUHP’s implementation is on hold for three years. And once it is implemented we are unlikely see an immediate widespread crackdown against dissidents of the sort seen in places like Turkey or Thailand. The code’s vague, nebulous provisions will probably be applied selectively and inconsistently. But this is precisely the point: uncertainty invokes fears and stifles dissent. The code’s provisions can be thought of as warning shots, designed to compel critics to adjust their behaviour.

There is no doubt this law resurrects elements of Indonesia’s authoritarian past. Democracy has been under extraordinary strain here for the past decade. The resilience of its civil society and parts of the media have helped to thwart some of the most brazen attempts to roll back democracy, like the 2014 proposal to end direct elections and Jokowi’s attempt to extend presidential term limits.

But aside from preserving the institution of elections, all of Indonesia’s other democratic norms and institutions are now under attack. The new criminal code is not the final nail in democracy’s coffin—but it gives a hammer to anyone who wants to drive one in.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss