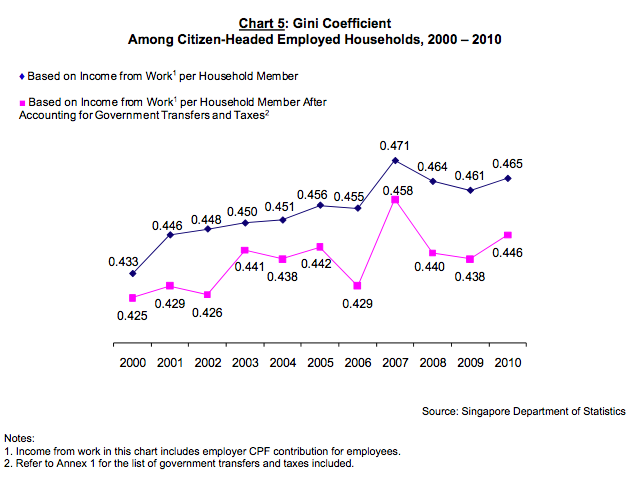

There have been growing concerns over rising income inequality in Singapore in the last decade. Based solely on income from work per household member, Singapore’s Gini coefficient has increased from 0.433 in 2000 to 0.465 in 2010. After accounting for government transfers and taxes, it has increased from 0.425 in 2000 to 0.446 in 2010. If returns from investment assets are taken into account, the Gini coefficient is likely to be much higher, as the rich are more likely to have surplus assets that they can invest for returns.

In contrast, the rest of Southeast Asia has similar or less inequality (as measured by the Gini coefficient) as compared to Singapore. According to the CIA World Factbook, Indonesia’s Gini coefficient is at 0.368, Philippines is at 0.458, Malaysia is at 0.462, and Vietnam is at 0.376. Only Thailand has a remarkably higher Gini coefficient at 0.536.

Recent academic work has suggested that high inequality within countries is highly correlated with a whole host of social ills. In the book “The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better”, Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett argue that high income inequality, rather than low average per capita income, is correlated with social ills such as crime, obesity, teen pregnancy, mental health, and drug addiction.

In Singapore’s case, although social ills are an increasing concern, they are less of a concern than the prospect of a permanent stratification of broader classes in society. Between 2001 and 2011, real incomes for the 20th percentile of the population saw no increase at all, whilst real median incomes only saw an increase of 11%. When placed alongside the statistic of increasing gini coefficient, this means that the rich are getting richer at a much faster pace than the rest of society. In addition, there are also concerns that social mobility has declined, with the less well off trapped in a cycle of poverty.

How should the Singapore government respond to this increasing income inequality?

On the one hand, government rhetoric has been clear and unambiguous. They acknowledge the problem and recognize that there needs to be increased social welfare provision, but abhor the creation of a welfare state such as in the Scandinavian, Japanese, or Australian models. For these government purists, Singapore, as a small country with no natural resources, needs to maintain financial prudence. The nightmare scenario is that increased social welfare provision, coupled with higher taxes to pay for these benefits, will kill the competitive work ethic of the population, make people lazy, and result in a downward spiral of the free-market competitiveness of the Singaporean economy in a globalized world. They point to the debt-ridden countries of Southern Europe and America as examples of this scenario. Most recently, Sim Ann (President’s Scholar, former career senior civil servant and the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) Member of Parliament) reiterated such a view in a newspaper commentary.[1]

On the other hand, some current and former senior civil servants have been quick to point out the crisis of inequality in Singapore, and strongly urge the government to chart a different course with respect to social welfare provision. Donald Low (former Director at the Ministry of Finance and Civil Service College) and Yeoh Lam Keong (currently Managing Director at the Government Investment Corporation of Singapore) co-wrote a commentary that was also published in the local papers, arguing that a much broader and inclusive social welfare provision strategy should be adopted, rather than targeted benefits for the poor.[2] They point to the success of generous government subsidies in the early years of Singapore’s industrial development, such as mass public housing and almost-free mass primary and secondary education.

These ongoing public debates about the level, type and form of social welfare policy should definitely be encouraged and are unlikely to die down any time soon. Yet one wonders whether these debates miss the point. Rather than debate about policy, the real debate could be about politics instead.

There is a significant agreement amongst political economists who study inequality, most notably the late Michael Wallerstein, that two key factors affect cross-country income inequality – first, the institutionalization and level of collective wage bargaining unions; and second, the role and presence of Left parties in competitive democratic governance. On these two issues, the Singapore story is simple: our unions are crippled due to their inability to strike and their close (some say subordinate) relationship with the ruling PAP; and, Left parties have little ideological traction and salience amongst the population, and are uncompetitive in elections organized under biased electoral rules.

The primacy of politics means that politics often has far-ranging social and economic consequences. At the risk of sounding overly pessimistic, the outlook for the still-authoritarian Singapore on the inequality front strongly suggests business-as-usual continuity rather than hopeful change.

[1] https://www.facebook.com/notes/sim-ann-ц▓ИщвЦ/tackling-inequality-charting-our-own-path/285475898170435

[2] https://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=305534386147209

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss