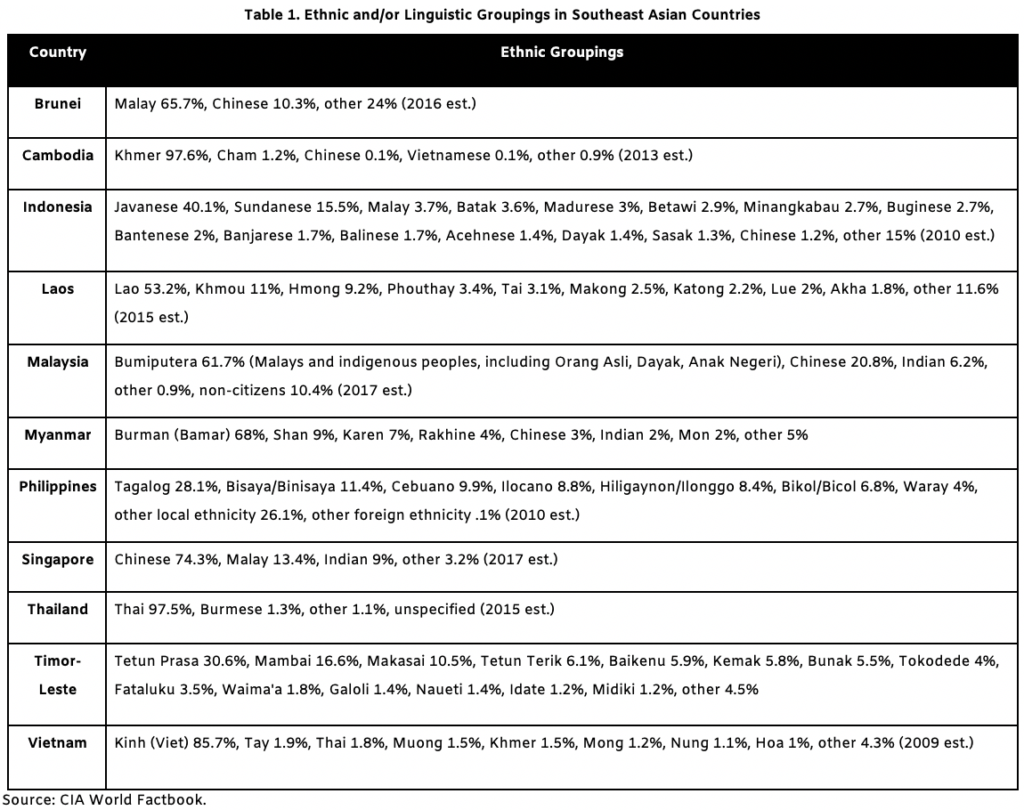

Southeast Asia is one of the most ethnically diverse regions in the world. A quick glance at its demographics would suggest that these countries may indeed be defined less by their 20th century-determined territorial barriers, and more by the multiplicity of languages and ethnic cultures residing in them.

What does this diversity mean for building a modern nation state?

In a study we conducted for our project, “Ethno-nationalisms in Southeast Asia”, we examined the relationship between ethnic homogeneity and regime type. This study is inspired by our observation that, while many have cited Southeast Asian countries as having exclusionary ethnic policies, more work needs to be done to understand ethnic exclusion as a regional trend and what it means for political practice.

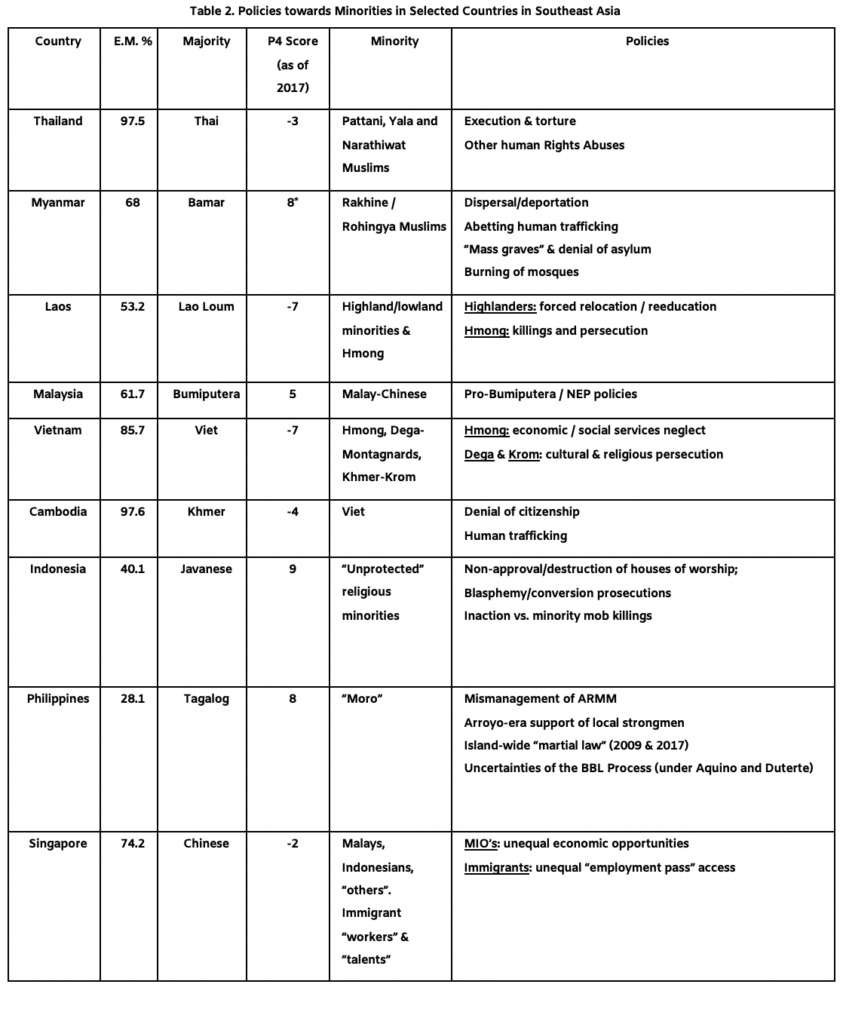

To investigate these issues, we examined ethnic homogeneity of each country in the region by regime type and compared it to cases of violence and exclusion against ethnic minorities. For ethnic homogeneity, we used population statistics from the World Factbook of the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and for regime type, we used The Polity IV Project, or P4 scores which indexes regime changes in all independent countries with total population greater than 500,000. The P4 scores captures this regime authority spectrum on a 21-point scale ranging from -10 (hereditary monarchy) to +10 (consolidated democracy).

Here’s what we found.

- The higher the ethnic homogeneity of a country, the lower its level of minority tolerance and openness for policy change. The table below demonstrates the government’s tendency to appeal to the largest common denominator of its population for legitimacy. For example, the Malaysian government implements Bumiputera policies, which prioritise ethnic Malay resources and benefits such as enrolments in universities over minorities such as the Chinese.

- Consequently, if the state can focus on appealing to a homogenous population, it can afford to ignore or discriminate against minorities with few repercussions. The clearest example of this is Singapore’s CMIO model which prioritises the Chinese majority in policy-making and welfare over the other minorities, namely the Malays, Indians and “others”.

- More revealing are the implications of ethnic composition with regime type. Countries like Thailand, Myanmar, and Laos, which have had long histories of autocratic and anocratic governments, have significant levels of population homogeneity. They are known to engage in explicitly violent and exclusionary policies against their minorities. This is evident in Myanmar, which has violently evicted around 700,000 members of the Rohingya minority since 2015.

- In contrast, less homogenous countries like Indonesia, the Philippines and Singapore deploy more institutional exclusion rather than physical violence. Institutional exclusion often takes the form of deprivation of legal rights and smaller allocations of welfare.

When there are cases of violence inflicted on minority groups by non-state actors, it is noticeable that the state does less to protect them. In Indonesia, the minority Ahmadiyah Islamic sect had been subjected to lynch mobs by conservative Muslims in 2011. No redress of justice was extended to minority victims, and the perceived inaction (or at worst, tacit endorsement) of President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono did not inspire confidence. The rise of Jakarta Governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, a Chinese-Indonesian popularly known as “Ahok”, also became a sore point for conservative Indonesian Muslims, leading them to conduct intimidation tactics against resident Chinese-Indonesians in a repeat of the horrific 1998 anti-Chinese riots.

What are the implications of these findings for the region? There are many, but we end this piece with two provocations.

First, such ethnic policies have implications on migration and labour exchange between member states. This is particularly observable in the Indochina countries, since some ethnic groups are minorities in their neighbouring countries. For example, the Viet ethnic group of Vietnam is a minority in Cambodia.

Imagined minorities: rethinking race and its appeal in Malaysia

Opponents of racism in Malaysia need to understand that proponents of racial politics do believe in race—and only by understanding the appeal of racial thinking can racism be defeated.

Second, regime types may act as a mediating variable of the state’s treatment of minorities. Though autocratic countries may deploy violence against minorities more openly, democratic countries, even flawed ones, presumably have norms and mechanisms against the deployment of violence against minorities. Furthermore, it is possible the ethnic composition of a country may have some influence with the country’s democratisation and its commitment to multiculturalism. Our discussion may contribute to the growing literature of democratisation throughout the region.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss