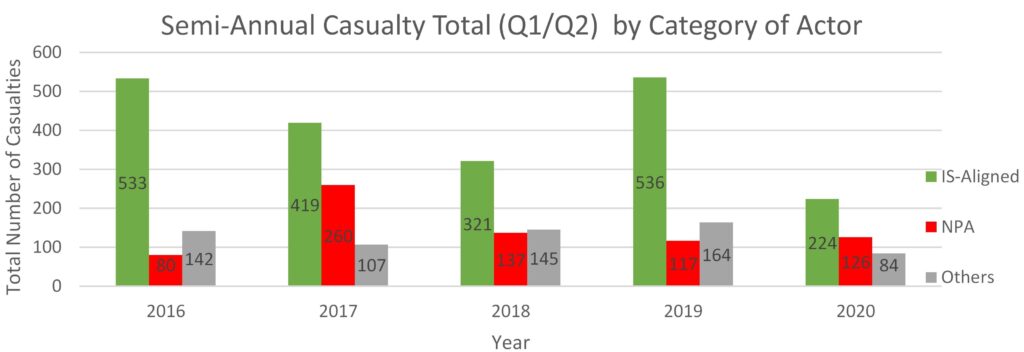

Between January 1 2016 and June 31 2020, my Political Violence in the Southern Philippines Dataset recorded 1,979 incidents of political violence that resulted in 5,928 total casualties among all categories of actors. This dataset excludes the 2017 siege of Marawi City. According to the data, Islamic State (IS) associated violence waned in Mindanao and Sulu during the COVID-19 pandemic, while the New People’s Army (NPA) has managed to sustain its operations. Although the factors driving these trends require further research, the differing material and organizational capacities of these actors likely explain why the NPA was able to commit more frequent acts of violence than IS-aligned groups.

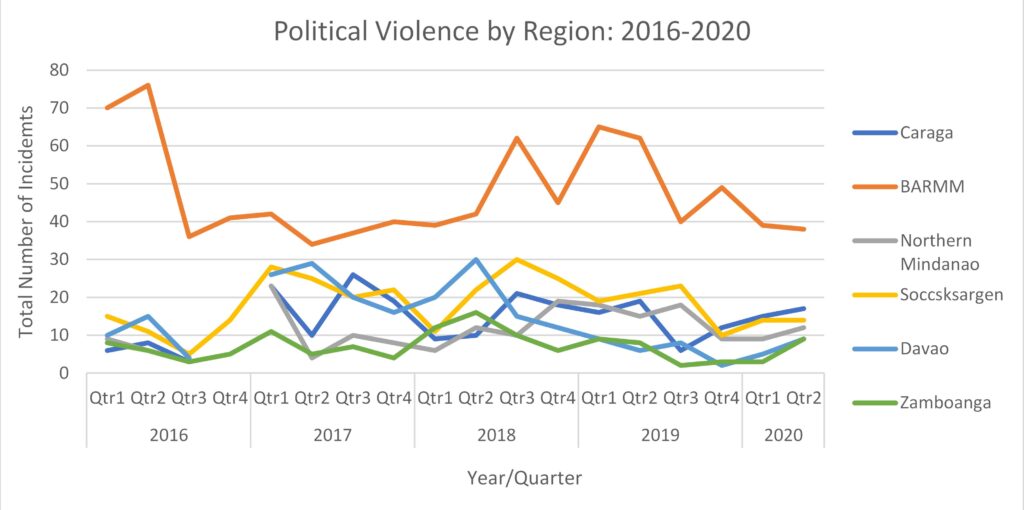

To determine whether or not higher number of COVID-19 cases coincided with higher numbers of incidents of political violence, this article compared administrative regional totals of violent incidents to publicly available epidemiological data. The islands of Mindanao and the Sulu archipelago that constitute the Southern Philippines are divided into 6 administrative regions depicted on the chart below. According to the Philippines’ Department of Health COVID-19 Dashboard, the Davao and Zamboanga regions accrued the highest total cases in Mindanao by June 30, while the Northern Mindanao region had the highest doubling rate of cases. Meanwhile, BARMM, SOCCSKSARGEN, and Caraga have among the lowest regional total cases in the country.

Of the administrative regions of Mindanao, the BARMM experienced the highest number of incidents with approximately 43% of the total number of incidents. However, between the first and second quarter of 2020 the number of incidents in the BARMM declined by a single incident. Although Q1 and Q2 of 2020 had about 60% of Q1/Q2 2019’s incidents and about 53% of Q1/Q2 2016’s incidents, this time period had almost the same number of incidents as the first half of 2017 and 2019. At the same time, the total number of incidents in SOCCSKSARGEN did not change, while all other regions of Mindanao experienced a slight increase.

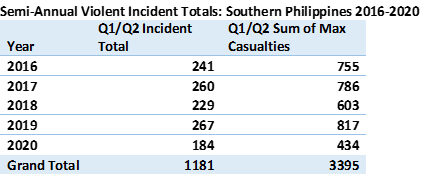

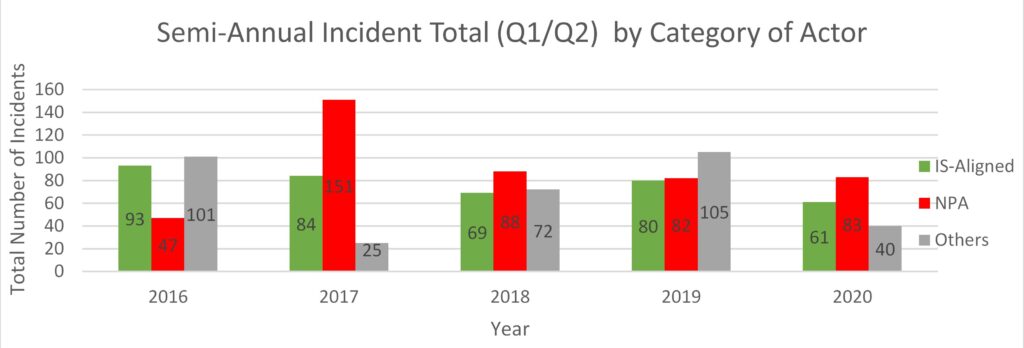

In order to make a proportionate comparison between the number of incidents per year from 2016-2020 that incorporates the minor administrative regional variations in violence discussed, this article compares incidents attributed to specific categories of actors from just the first two quarters of each year. The data is thus divided into three major categories of actors engaged in violence in the Southern Philippines: IS-aligned Groups, the NPA, and Others.

IS-aligned groups are predominantly Moro militant groups that have formally sworn bay’ah to the Islamic State or less formally pledged support. The NPA is comprised of various guerilla fronts and peoples’ militias of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP). The category of “Others” is the most heterogenous, and includes unidentified belligerents engaged in political violence (e.g. unknown gunmen seen escaping the scene of an attack).

Compared to the previous four years, the Southern Philippines as a whole experienced significantly less violence in 2020 in terms of both the number of violent incidents and the number of casualties resulting from those incidents.

While this trend is notable, a more dramatic trend emerges when the data is filtered by the aforementioned categories of actors.

By breaking down conflict intensity (the number of incidents and casualties) by category of actor, two major trends become visible. First, the declining violence in the first half of 2020 relative to prior semi-annual totals resulted from a sharp decline in violence from IS-affiliated actors, and a lesser decline in violence by actors within the “Others” category. Second, NPA incidents and associated casualties in 2020 fluctuated within a narrow band of semi-annual totals of the previous two years. The heightened NPA conflict intensity of 2017 and the NPA lower conflict intensity of 2016 were, at least in part, the result of the Duterte administration’s ceasefire and subsequent breakdown of negotiations with the NPA.

This data analysis strongly suggests correlations between COVID-19 and the commission of political violence by certain categories actors, but the causal mechanisms driving these trends are less clear. The decline in violent incidents perpetrated by IS-affiliated groups supports the argument made by Senior Analyst for the International Crisis Group Georgi Engelbrecht, who contends that IS-affiliate groups were concentrating on weathering the pandemic, rather than exploiting it through violence or propaganda. Indeed, beyond limited messaging from IS-affiliated accounts on social media, the IS response to the pandemic in the Philippines is muted.

According to Armed Forces of the Philippines Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. Gilbert Gapay, 10%-15% of the armed forces’ budget was realigned from socio-economic counterinsurgency programming to support COVID-relief efforts. However, vulnerable and displaced peoples throughout Mindanao are finding it difficult to access relief under quarantine conditions, with lockdown measures hindering the delivery of aid to critical areas such as Marawi City. IS-affiliated factions have reportedly incorporated these grievances into their local recruitment activities.

In addition to this shift in messaging, state security personnel enforcing quarantine measures have become occasional targets of opportunity for both IS-affiliated groups and the NPA. The data, which is not all-inclusive, captured 4 instances of militants targeting such personnel in the towns of Pantukan (4/7), Datu Hoffer Ampatuan (5/3), Rajah Buayan (5/19), and Mamasapano (5/24). Apart from these tactical adaptations, IS-affiliates in the Philippines have yet to demonstrate any shift in strategy in response to COVID-19. That is not to say that IS-affiliates will not exploit the hardships of COVID-19 in the Philippines; spectacular acts of violence such as the 2020 Jolo Suicide Bombings are evidence enough of that intent. Given the ideological and interpersonal divisions between and within IS factions, and limited capacity for local governance, IS-aligned groups are not particularly well-positioned to thrive amidst the pandemic.

By contrast, the NPA has more capacity to endure COVID-19 as a much larger, nationally organized insurgency. With an estimated 4,000 fighters reportedly based in over 200 towns across the nation, in addition to thousands of political volunteers, and the centralized political leadership and propaganda output of the CPP, the NPA is well positioned to continue its operations during the pandemic. According to US Embassy reporting, it is believed that the apparent increase in NPA recruitment and activity during the pandemic was owed to its capacity to alleviate the economic hardship brought on by quarantine measures through the provisioning of food and salaries to its members.

The resilience of NPA guerilla fronts is frequently explained in terms the systemic extortion of local industries and communities by imposing “revolutionary taxes”, however contemporary knowledge of NPA fundraising is typically limited to revelations from specific sectors of the economy such as illegal logging in Caraga. Even more opaque are the NPA’s recruiting efforts; despite frequent announcements of mass surrenders, the ranks of the NPA seldom seem to dwindle. In the end, how the NPA is managing to offset the deleterious impacts of COVID-19 is not altogether clear.

In the Philippines, local governments are stepping up to cover gaps in national public health and welfare infrastructure.

Mayors are keeping the Philippines afloat as Duterte’s COVID-19 response flails

Ultimately, research on political violence in the Philippines is constrained by the paucity of publicly available information on violent actors, owed in large part to the covert orientation of these actors. Incident tracking is a useful research method in this regard, since it records the violence committed by the NPA, IS-aligned groups, and other violent non-state actors, but the number of incidents and casualties incurred from those incidents is just one facet of studying political violence.

To understand why political violence is pervasive but varied during the pandemic, more thorough research into the organizational structures of guerilla fronts, terrorist cells, and other assemblages of violent actors must be prioritized. A relatively small community of scholars and journalists have taken on the onerous task of mapping and profiling actors like the Maute Group and the Abu Sayyaf Group, but similar work on the NPA and other actors is lacking, with some exceptions. Until a more robust research program studying the organizational structures and capacities of violent non-state actors in the Philippines is developed, the ability of scholars to explain and anticipate trends in incidents will remain limited.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss