Regarded as a bastion of the New People’s Army (NPA), Mindanao in the Southern Philippines has experienced a decline in communist insurgent activity. If one were to follow the official communications coming from the Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process and the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), this news might not be surprising. Testing these claims against independently gathered open-source data, I recorded a clear reduction in the number of violent incidents involving the NPA from 2017 to 2019.

While descriptive statistics illustrate this overall trend, they do not validate official forecasts predicting the end of the NPA by 2022. The reasons why NPA incidents declined overall are not self-evident, but explanations including the heightened presence of security forces in Mindanao, the recently revamped and localised peace process, and the strategic decision making of the NPA offer plausible hypotheses.

The Data

As of this writing, The Political Violence in the Southern Philippines dataset records and encodes 1798 incidents of political violence between 1 January 2016 and 31 December 2019 on the islands of Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago. Data were gathered from local, regional, national, and foreign reporting outlets, in addition to reports produced by civil society groups and Philippine government memos. From the total of the set, the NPA was in involved in 628 incidents of political violence during this 4-year period. When reviewing these findings, recall that this set captures violence only in the Southern Philippines, and does not provide direct insight into the activities of groups like the NPA that operate nationwide.

As visualised above, the number of NPA-related incidents steadily declined between 2017 and 2019, but have not returned to the lows of 2016, which were an outlier resulting from the peace negotiations and ceasefire occurring that year.Moreover, the intensity of violence in terms of both injuries and fatalities also declined each subsequent year, with the minor exception of 2016 having a higher ratio of injuries and fatalities to incidents than 2018 and 2017 and 2019.

As visualised above, the number of NPA-related incidents steadily declined between 2017 and 2019, but have not returned to the lows of 2016, which were an outlier resulting from the peace negotiations and ceasefire occurring that year.Moreover, the intensity of violence in terms of both injuries and fatalities also declined each subsequent year, with the minor exception of 2016 having a higher ratio of injuries and fatalities to incidents than 2018 and 2017 and 2019.

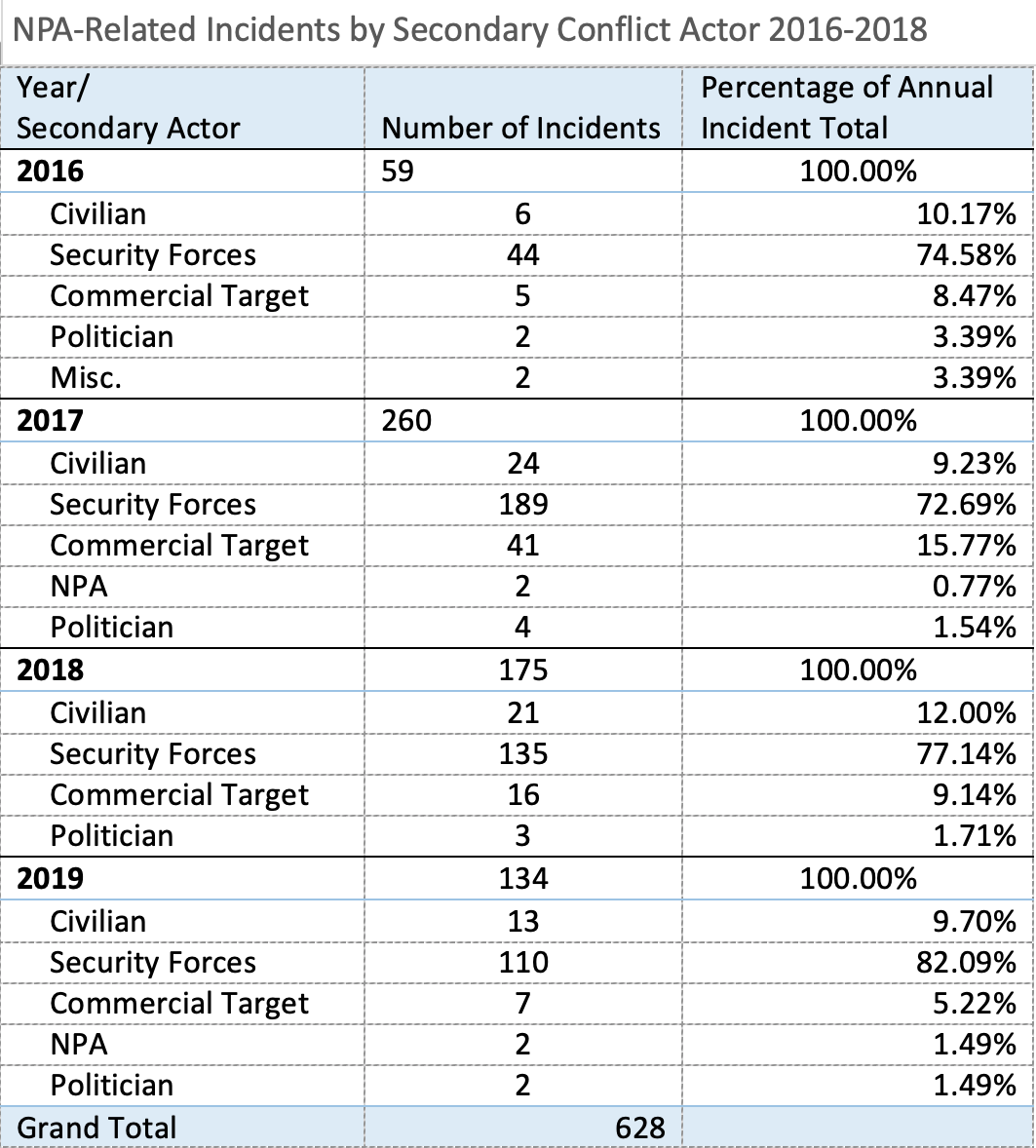

To understand which actors engaged with the NPA in related incidents, the data are coded into conflict dyads, in which the identities of actors involved are divided into general categories. Breaking down the incident-level data into conflict dyads, in which one actor is the NPA, while the other actor can range from police, soldiers, and state militias (Security Forces), commercial property and associate persons (e.g. workers) , politicians, civilian, other NPA (due to intragroup feuding), and miscellaneous actors to include unknown persons, little variation was observed. Civilians make up a consistent percentage of targets for the NPA year to year.

Confrontations with security forces were always the most common, but have reached a new high in 2019 with such incidents comprising 82% of all incidents that year.

Incidents were also coded geographically according to the province in which they occurred, revealing more dynamic trends. From 2016 to 2019, NPA incidents were observed in all 22 mainland provinces of Mindanao, and none were observed in the outlying island provinces of Basilan, Sulu, Tawi-Tawi, Camiguin, and Dinagat, where the Abu Sayyaf Group and other violent non-state actors are known to operate.

Out of the 22 provinces of Mindanao, the same 5 provinces of Bukidnon, Agusan del Norte, Compostela Valley (renamed Davao del Oro in December 2019), Cotabato, and Davao del Sur experience the greatest number of incidents each year. As shown in the graph above, there were notable changes in the number of incidents observed in each of these provinces from 2016-2019. During this timeframe, only Bukidnon experienced a net increase in incidents, while the rest experienced a relatively gradual decline. In addition, all 5 provinces experienced a substantial increase in the number of incidents from 2016 to 2017, but none more so than Cotabato, where by 2019 NPA incidents had not yet declined to their 2016 level.

Incidents in Agusan del Norte, Bukidnon, and the former Compostella Valley correlate with salient common features of these provinces, including extensive agribusiness and extractive industries ripe for NPA extortion, as well as difficult geographic terrain and porous provincial borders that inhibit the pursuit and scouting operations of security forces. Davao del Sur maintains an active NPA presence for these reasons as well, but the NPA’s presence in the province is more intrinsically linked to decades of urban operations in Davao City, which is geographically located in but administratively separated from Davao del Sur. The NPA also has historical ties to Cotabato, but its presence and influence ebbs and wanes with the activities of the province’s Moro insurgents.

In these data, there was a modest decline in NPA-related incidents in Mindanao over the past four years, albeit with several important caveats. Despite the decrease in the total number of NPA-related incidents and casualties across Mindanao from 2017 to 2019, the total for 2019 is still substantially higher than the total for 2016. In addition, the per-annum percentage of incidents involving commercial targets declined to a record low in 2019, but the percentage involving civilians remained stable, and the percentage of encounters with security forces rose. Finally, despite the decline in incidents across the top 5 provinces in Mindanao, Bukidnon continues to rise as a site of violence between the NPA and other actors. Clearly the NPA’s experience in Mindanao changed considerably over this period of time, but the data does not support official narratives of their decline.

The escalating violence of the New People’s Army in Mindanao

Despite Manila's push for peace, the NPA shows no signs of coming to the table.

First, Martial Law in Mindanao provided more effective controls on the movement of arms and personnel across Mindanao. This has already been argued at length by International Alert, Philippines. The application of Martial Law might explain the percentage increase in the number of clashes between the NPA and Security Forces, while also suggesting that an increased security presence “hardened” the defences of commercial properties usually targeted by the NPA. If this argument is true, then the expiration of Martial Law on 31 December, 2019 should produce more violent incidents in 2020.

The second is that the implementation of Executive Order (EO) 70 actually succeeded in its mission of countering the NPA by creating overlapping government task forces empowered to pursue localised peace talks with NPA fronts across the country. Signed 4 December 2018, EO70 put the onus of civilian counterinsurgency efforts on regional and local governments, most notably through the designation of the NPA as persona non grata within their territories, and the promotion of the Enhanced Comprehensive Local Integration Program.

This drive towards localising the conflict is controversial, however. The Philippines’ Commission of Human Rights has called upon the Duterte administration to rescind the order, alleging that “…it has been consistently used to justify threats and intimidation of individuals and organisations working for the improvement of the human rights and welfare of various marginalised, disadvantaged, and vulnerable sectors of society…” Such abuses of human rights may have undermined the EO 70’s stated intent, or at least nullified its potential to win hearts and minds. While President Duterte continues to toy with the concept of reviving talks between his administration the Communist Party of the Philippines, the government’s official position still resides with EO70 and the pursuit of localised talks.

The third hypothesis is that the declining NPA violence in Mindanao is a product of NPA strategic posturing. As founder of the Communist Party of the Philippines Jose Maria Sison noted, different geographic commands “shine” at different times during armed revolutions. Following the guerrilla truism of attacking where the enemy is weak and withdrawing where they are strong, the NPA has a long history of transferring fighters away from areas saturated by the AFP, and launching new offensives in less-defended and more cooperative areas.

The declining activities of the NPA in Mindanao coincide with high profile offensives in Negros, Samar, Leyte, and Southern Luzon; as the AFP redeploy to these areas and even pull out of Mindanao, we could see a return of the NPA to the Southern Philippines. Further, the termination of the Visiting Forces Agreement with the US could jeopardise the Philippines access to American military aid. With the spectre of fewer resources to draw on in the absence of American support, the end of the NPA’s 51-year-old insurgency is anything but assured.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss