ฉบับภาษาไทยอยู่ข้างล่าง

Anthropology as a discipline in Thailand, and with it the studies of rural villages, blossomed during the Cold War under the influence of the military government and the United States. The goal of anthropology—from the state’s perspective—after World War II was the amassing of information on Thailand’s rural regions as part of the struggle against the communist threat. The “village” has been a fundamental unit of analysis used by Thai social scientists ever since. We have seen this in writing on the Red Shirt movement, which so often begins with attempts to come to grips with changes in Thailand’s countryside—as if the village is by necessity the fundamental unit of analysis.

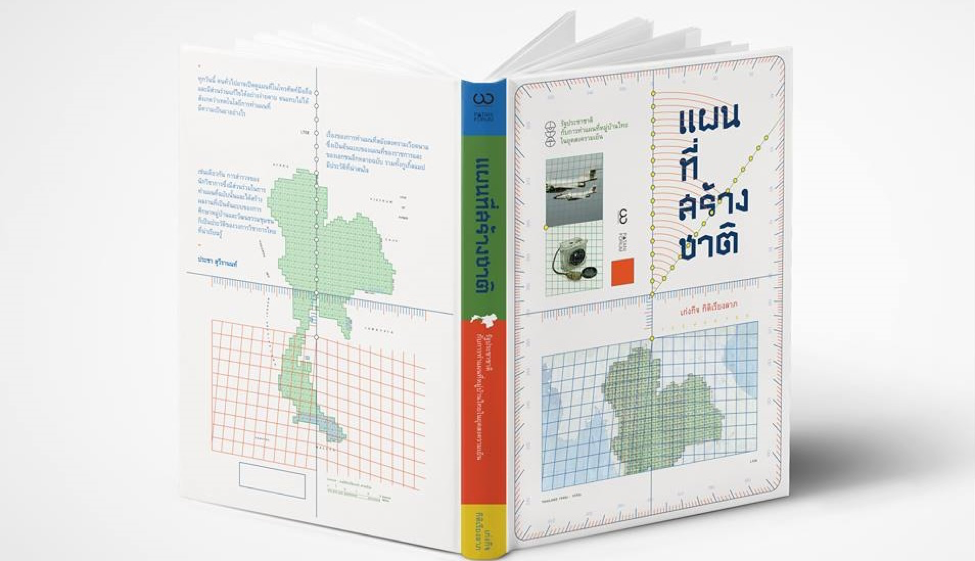

My new book Mapping the Nation argues that villages in Thailand were constructed not only as analytical units during the Cold War. Their construction in the basic sense of being tangible spaces was also shaped by the process of drawing maps from aerial photographs and the physical surveying of villages. The process of constructing villages as physical spaces translated into reality their status as analytical units within the knowledge-making practices of US and Thai social scientists.

From 1951–69, the US Army Map Service compiled the Series L708 map in agreement with the government of Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram, the first map of Thailand drawn at a scale of 1:50,000. The base unit that the map employs is mu ban (village)—a term which had never before appeared on a map of Siam/ Thailand. A decade later, the Series L708 map was amended into Series L7017. Official maps of Thailand since then have all been based upon Series L708 and L7017.

Suthep Soonthronpasuch, an anthropologist who worked alongside Lauriston Sharp and Lucien Hanks under the Bennington-Cornell Survey of Hill Tribes (1963–74) in Thailand’s northern provinces, recalls that Hanks and Sharp carried Series L708 maps (despite their status as classified state documents at the time). According to Soonthornpasuch, Hanks and Sharp conducted their study by referring to the L708 maps for the locations of hill tribe villages, before travelling to compile information on the inhabitants there. Undoubtedly, several other Thai and US social scientists drew upon these maps in studies of villages in Northern and Isaan provinces (Soonthornpasuch himself was simultaneously employed at the US military’s Advanced Research Projects Agency). In this way, we can begin to see how maps were used as a technique of power during the Cold War.

As I dug deeper into maps, I began to wonder: how were communities that lived at the peripheries of state power arranged before the Series L708 maps? According to the field notes of Lucien Hanks, the “villages” he surveyed every five years in 1964, 1969 and 1974 progressively could not be found, since most were nomadic and moved continuously. These “villages” apparently did not have leaders, headmen or permanent governance structures, but lived fluidly. I began to muse on another question: when did the Thai state penetrate the lives of those living at its borders? When did these nomadic groups begin to settle permanently, hold identity cards—when did they even begin to call themselves “Thai”?

A survey conducted by the Tribal Research Centre across the decade of 1970–80 found that prior to 1970, many people in the tribal regions did not have identity cards, did not have permanent residences and were not interested in whether they were Thai or not. But when we near the end of the 1970s, and step into the 1980s, ‘villages’ characterised by permanent residences, and identity cards that list addresses and nationality, were becoming a nation-wide phenomenon. In the context of the Cold War, all these sources of surveillance and identification were exploited by the Thai state to build allegiance and counter communism.

In retrospect, we might conclude that ‘Thainess’ only truly laid down its roots at the end of the 1970s. While the Siamese state surely yearned to exercise control over its territory and peoples since ancient times, it lacked the necessary mechanisms to penetrate lives and territories at its peripheries. Even the absolutist state of Rama V, who oversaw the state’s modernisation, lacked the required technologies and knowledge of the peoples inhabiting the kingdom’s borders, and could only hope to fully extend its power.

What defined the Thai state from the Cold War era was that it could construct visual knowledge of what it governed. In contrast to the past—when the rural regions were conceptualised solely through description and imagination—technologies of aerial photography, mapping and anthropological surveying allowed the Thai state to ‘discover’ villages and devise methods to invest them with ‘Thainess’.

Perhaps I will conclude by picking an argument with Thongchai Winichakul’s Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-Body of a Nation. Thongchai drew the critical conclusion that maps drawn during Rama V gave birth to the nation as we know it—this is the conclusion my book seeks to shatter. The drawing of maps was one way by which Rama V constructed the boundaries of the absolutist Thai state. But these maps were without substance: they did not have details that could speak to the people and ways of living at the edges of the state. The maps of the Rama V era were as such ‘maps of the state’, but not ‘maps of the nation’. They did not give rise to a consciousness of ‘Thainess’ in the hearts of that era’s people.

In contrast, the maps that were created in the aftermath of World War II reflected in various details the expansion of the state’s power into multiple levels of society. What followed was governance through the nurturing of consciousness of the nation and ‘Thainess’. My book represents a questioning of the theory that the Thai nation was a 19th century invention. The nation and nationalism have found consciousness in the everyday lives of people on the peripheries of the state only as recently as the past 50–60 years. ‘The nation’ could be born only with the maps that were created just a few decades ago.

งานวิจัยเกี่ยวกับกำเนิดมานุษยวิทยาในประเทศไทยในยุคสงครามเย็นของผู้เขียนก่อนหน้านี้พบว่า วิชามานุษยวิทยาและการสำรวจหมู่บ้านชนบทเฟื่องฟูขึ้นมาในยุคสงครามเย็น โดยเฉพาะบทบาทของสหรัฐอเมริกาและรัฐบาลเผด็จการทหารของไทย เป้าหมายสำคัญของวิชามานุษยวิทยาในยุคหลังสงครามโลกครั้งที่ 2 ก็คือ การหาข้อมูลเกี่ยวกับชนบทไทยเพื่อสู้กับภัยคอมมิวนิสต์ “หมู่บ้าน” กลายมาเป็นหน่วยของการวิเคราะห์ (unit of analysis) พื้นฐานของนักสังคมศาสตร์ไทยนับแต่นั้นมา ดังที่เราจะเห็นได้จากงานวิจัยและงานเขียนเกี่ยวกับขบวนการเสื้อแดงในช่วงหลังมานี้ก็กลับไปเริ่มต้นด้วยการทำความเข้าใจความเปลี่ยนแปลงในหมู่บ้านชนบท ประหนึ่งว่าหมู่บ้านเป็นหน่วยที่จำเป็นพื้นฐานของการหาความรู้

A conversation with Thanathorn, Future Forward Party founder

Thanathorn has made clear that the Future Forward Party has no intentions of being a Pheu Thai shadow.

ภายใต้บรรยากาศของสงครามเย็น กระบวนการสร้างหมู่บ้านกายภาพดังกล่าวเสริมทัพให้หมู่บ้านในฐานะหน่วยของความรู้ดูสมจริงมากขึ้นภายใต้ชุดความรู้ของสหรัฐอเมริกาและสังคมศาสตร์ไทย

แผนที่ฉบับ L708 ซึ่งทำขึ้นโดยหน่วยงาน US Army Map Service ท่ามกลางข้อตกลงกับรัฐบาลจอมพล ป. พิบูลสงครามในปี 1951 ซึ่งใช้เวลาในการดำเนินการแล้วเสร็จในปี 1969 กลายมาเป็นแผนที่มาตรฐานที่มีมาตราส่วน 1:50,000 ฉบับแรกของไทย และหน่วยพื้นฐานที่ปรากฏในแผนที่ฉบับดังกล่าวก็คือ “หมู่บ้าน” (village) ซึ่งไม่เคยปรากฏมาก่อนบนแผนที่ของสยาม/ไทยก่อนหน้านั้น

นอกเหนือจากแผนที่ฉบับ L708 แล้ว สหรัฐฯยังทำแผนที่ฉบับอื่นอีก เช่น L9013 ซึ่งมีมาตรฐานส่วนละเอียดถึง 1:12,500 และหลังจากนั้นอีกกว่าทศวรรษ ได้มีการปรับปรุงแผนที่ L708 จนกลายเป็น L7017 ซึ่งแผนที่ที่ทำขึ้นในช่วงหลังจากนั้นทั้งหมดในประเทศไทยก็อ้างอิงกับฉบับ L708 และ L7017 ตามลำดับ

สุเทพ สุนทรเภสัช นักมานุษยวิทยารุ่นบุกเบิกซึ่งในขณะนั้นทำงานให้กับ ARPA หรือ Advanced Research Projects Agency ซึ่งเป็นหน่วยวิจัยและห้องสมุดของกองทัพสหรัฐในประเทศไทย ซึ่งในช่วงเวลาเดียวกันเขาได้เข้าร่วมโครงการสำรวจหมู่บ้านชาวเขาในภาคเหนือร่วมกับ Lauriston Sharp และ Lucien Hanks ภายใต้โครงการ Bennington-Cornell Survey of Hill Tribe (1963-1974) เล่าว่าคณะของ Hanks และ Sharp ถือแผนที่ฉบับ L708 ซึ่งในขณะนั้นเป็นเอกสารลับของทางราชการไปด้วย โดยจะดูว่ามีกลุ่มบ้านกระจุกตัวอยู่ตรงตำแหน่งไหนของแผนที่ และคณะสำรวจจะเดินไปตรงนั้นเพื่อเก็บข้อมูล แน่นอนว่า นอกจากคณะสำรวจดังกล่าว นักมานุษยวิทยาอเมริกันและนักมานุษยวิทยาไทยอีกหลายคนก็ใช้แผนที่ฉบับเดียวกันนี้ในการสำรวจและทำวิจัยสยามเกี่ยวกับหมู่บ้านไทยทั้งในภาคเหนือและภาคอีสาน

ในแง่นี้ แผนที่และวิชาภูมิศาสตร์จึงเป็นสิ่งที่สำคัญไม่น้อยไปกว่างานวิจัยภาคสนามและวิชามานุษยวิทยา ในฐานะที่ทั้งสองวิชาเป็นวิชาหรือเทคนิคของอำนาจของจักรวรรดิอเมริกันในยุคสงครามเย็น

ในกระบวนการค้นคว้าเกี่ยวกับแผนที่ ผู้เขียนฉุกคิดขึ้นมาว่า ก่อนหน้าที่จะมีแผนที่ L708 การตั้งถิ่นฐานของผู้คนที่อยู่ห่างไกลอำนาจรัฐเป็นเช่นไร ผู้เขียนได้คำตอบเรื่องนี้จากบันทึกของ Lucien Hanks ซึ่งเล่าว่า หมู่บ้านที่เขาสำรวจทุกๆ 5 ปี (1964, 1969 และ 1974) ได้หายไปหน้าตาเฉย และแทบทุกหมู่บ้านเคลื่อนที่ไปเรื่อยๆ หมู่บ้านเหล่านั้นไม่มีหัวหน้าหมู่บ้าน ไม่มีผู้ใหญ่บ้าน หรืออำนาจปกครอง แต่อยู่อย่างเป็นอิสระ ส่งผลให้ผู้เขียนเริ่มตั้งคำถามอีกคำถามว่า รัฐไทยเข้าถึงชีวิตผู้คนในเขตแดนของตนเองตั้งแต่เมื่อไร แน่นอนว่าสิ่งเหล่านี้ต้องมีตัวชี้วัด เบื้องต้นที่สุดก็คือ การที่ผู้คนหยุดอยู่กับที่ มีบัตรประชาชน หรือความภักดีกับรัฐไทย หรือแม้แต่การนิยามตัวเองว่าเป็น “คนไทย”

ข้อสงสัยดังกล่าวนี้ชัดขึ้นเมื่อพิจารณาการสำรวจหมู่บ้านของนักมานุษยวิทยาอีกหลายคนในทศวรรษ 1960-1970 และงานสำรวจของศูนย์วิจัยชาวเขาในทศวรรษ 1970-1980 พบว่า ก่อนหน้าทศวรรษ 1970 คนจำนวนมากไม่มีบัตรประชาชน ไม่มีหลักแหล่งที่อยู่ และไม่สนใจว่าพวกเขาเป็นคนไทยหรือไม่ แต่เมื่อย่างเข้าสู่ปลายทศวรรษ 1970 และต้นทศวรรษ 1980 “หมู่บ้าน” ซึ่งหมายถึงการตั้งถิ่นฐานอยู่กับที่ และมีบัตรประชาชนที่ระบุที่อยู่และสัญชาติที่แน่นอนเพิ่งจะเกิดขึ้นทั่วประเทศไทย แน่นอนว่าหากพิจารณาผ่านบริบทของการต่อต้านคอมมิวนิสต์ สิ่งเหล่านี้ก็เป็นเครื่องมือที่รัฐไทยใช้ในการสร้างความภักดีและต่อต้านคอมมิวนิสต์เป็นสำคัญ

มาถึงจุดนี้ เราอาจสรุปได้ว่า ความเป็นไทยหรือการเป็นคนไทยเพิ่งจะลงหลักปักฐานจริงๆก็ในปลายทศวรรษ 1970 เท่านั้นเอง

แม้ว่ารัฐสยามจะมีแรงปรารถนาในการปกครองผู้คนและพื้นที่มาตั้งแต่โบราณ แต่รัฐสยามก็ไม่มีเครื่องมือมากพอในการเข้าถึงผู้คน พื้นที่ และสร้างความภักดีให้เกิดขึ้นทั่วไปได้ ปฏิเสธไม่ได้ว่ารัฐสมบูรณาญาสิทธิ์ในสมัยพระจุลจอมเกล้าซึ่งเป็นรูปแบบรัฐในช่วงเปลี่ยนผ่านสู่รัฐสมัยใหม่ก็ต้องการการขยายแผ่ของอำนาจ แต่รัฐดังกล่าวก็มีข้อจำกัดในตัวเองคือขาดแคลนเทคโนโลยีและความรู้

ความพิเศษของรัฐไทยในยุคสงครามเย็น ก็คือ มันสามารถหยิบฉวยเอาเทคโนโลยีใหม่ๆเข้ามาเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของตนเอง เฉพาะเจาะจงกว่านั้นก็คือ รัฐประชาชาตินั้นมีเครื่องไม้เครื่องมือที่จะสามารถสร้างความรู้ที่วางอยู่บนการสร้างภาพ (visualisation) ต่อสิ่งต่างๆที่มันปกครอง จากเดิมที่บ้านนอกเป็นเพียงสิ่งที่ถูกถ่ายทอดผ่านเรื่องเล่าให้จินตนาการกันเอาเอง ด้วยการสนับสนุนของเทคโนโลยีการถ่ายภาพ การทำแผนที่ และการสำรวจของนักมานุษยวิทยา และเมื่อรัฐเชื่อว่าตนเอง “ค้นพบ” หมู่บ้าน รัฐถึงจะหาวิธีขยายความเป็นไทยเข้าไปได้

ตอนท้ายของ “แผนที่สร้างชาติ” ผู้เขียนทดลองสร้างข้อโต้แย้งที่ท้าทายกับหนังสือ Siam Mapped: A History of a Geo-body of a Nation ของ Thongchai Winichakul ซึ่งเสนอข้อเสนอสำคัญต่อวงการวิชาการไทยว่า แผนที่ที่สร้างขึ้นในสมัยรัชกาลที่ 5 ได้ให้กำเนิดความเป็นชาติ นี่คือข้อเสนอที่ผู้เขียนต้องการหักล้าง ในขณะที่รัชกาลที่ 5 ตีเส้นเขตแดนผ่านแผนที่ แผนที่ดังกล่าวก็ไม่ได้เป็นอะไรที่มากไปกว่าการสร้างขอบเขตของรัฐสมบูรณาญาสิทธิ์ แต่มันไม่มีโครง ไม่มีรายละเอียดที่จะระบุถึงผู้คนและบ้านเรือนที่อยู่ในขอบเขตของรัฐดังกล่าว แผนที่สมัยรัชกาลที่ 5 จึงน่าจะเป็น “แผนที่ของรัฐ” มากกว่าจะเป็น “แผนที่ของชาติ” เพราะแผนที่ฉบับดังกล่าวไม่ได้นำไปสู่การเกิดขึ้นของสำนึกของความเป็นชาติในจิตใจของผู้คนในสมัยนั้น

แผนที่ที่สร้างขึ้นในช่วงหลังสงครามโลกครั้งที่ 2 ซึ่งมีรายละเอียดต่างๆต่างหากที่สะท้อนว่าอำนาจของรัฐได้ขยายเข้าสู่ชีวิตของผู้คนในระดับต่างๆของสังคม และสิ่งที่ตามมาก็คือการปกครองผ่านการสร้างจิตใจของความเป็นชาติและความเป็นไทย ในแง่นี้ หนังสือเล่มนี้จึงเป็นความพยายามที่จะตั้งคำถามต่อการมองชาติและชาตินิยมว่าเป็นสิ่งประดิษฐ์ของศตวรรษที่ 19 โดยเสนอว่า ชาติและชาตินิยมสามารถทำงานในชีวิตประจำวันของผู้คนได้ก็เมื่อไม่เกิน 50-60 ปีที่ผ่านมาเท่านั้น และความเป็นชาติเหล่านี้เกิดได้ก็ต่อเมื่ออาศัยแผนที่ของชาติที่สร้างขึ้นมาไม่กี่ทศวรรษที่ผ่านมา

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss