Though often overshadowed by Thailand’s monarchy and military, the Royal Thai Police has been and remains a crucial actor across the kingdom’s political and security landscape. With an estimated 230,000 officers, police are tasked with guaranteeing domestic law and order as experts in institutionalised violence separate from but almost equal in size with the army (itself containing approximately 245,000 officials). Since 1936, certain individuals have succeeded in personalising control over the police, while the army has sought time and again to control or emasculate it.

Origins of the army–police rivalry

Created in 1860 under King Rama IV, the police was initially a foreign-led force: 4 of its first 5 commanders were non-Thais (3 Brits and a Dane). In 1932 Police Commander Phraya Atikhorn unsuccessfully prevented the coup which overthrew absolute monarchy, but in 1933 police led by Police Commander Phraya Anusorn Turagan played an instrumental role in defeating the arch-royalist Boworadej rebellion. From 1936 until 1945 Adul Aduldecharat led the police, carving out a powerful fiefdom as a dreaded enforcer especially during Phibun Songkram’s autocracy.

It was in 1936 that the clash between Thailand’s army and police bureaucracies commenced. At that time, General Phraya Phahon’s hold on the post of army chief was slipping while the ambitious Adul was commencing his career as police commander. Phibun served as prime minister and army commander from 1938 until 1944 but he relied on Adul to keep order. Unbeknownst to Phibun, Adul during World War II secretly worked with the anti-Axis Seri Thai. When Phibun left office in 1944, civilians led by Pridi Banomyong came to the fore in an effort to democratise Thailand. Realising that Phibun was still popular with the army, Pridi needed reliable and capable security agencies to prevent an army coup. In 1946 he recruited Adul to serve as army commander while appointing Admiral Thawan Thamrongnawasawat as prime minister in August of that year. Both decisions were made to diminish army power in favor of enhanced police and naval support. In fact, following a suggestion from Pridi, Adul had agreed to succeed Thawan as prime minister. But this scheme—which would have further enhanced police power—was prevented by the November 1947 putsch.

Since 1947, the army has time and again attempted to rein in the police. In many cases, it has resorted to coups.

When General Phin Chunhavan became army commander in 1948, he placed his son-in-law Colonel Phao Sriyanond in a senior police command position, making him police chief in 1951. The move created army-police harmony until Phin’s retirement in 1954. The United States became a patron to Phao, delivering assistance and training a newly organised Border Patrol Police, among other police paramilitary organisations. However, Phin’s successor Gen. Sarit Thanarat increasingly confronted Phao and Prime Minister Phibun (who had returned to office in 1948). In 1957 the two were forced into exile, leaving Sarit to dominate Thailand. In 1959 he became police commander in addition to his posts as premier and army commander, serving until his death in 1963.

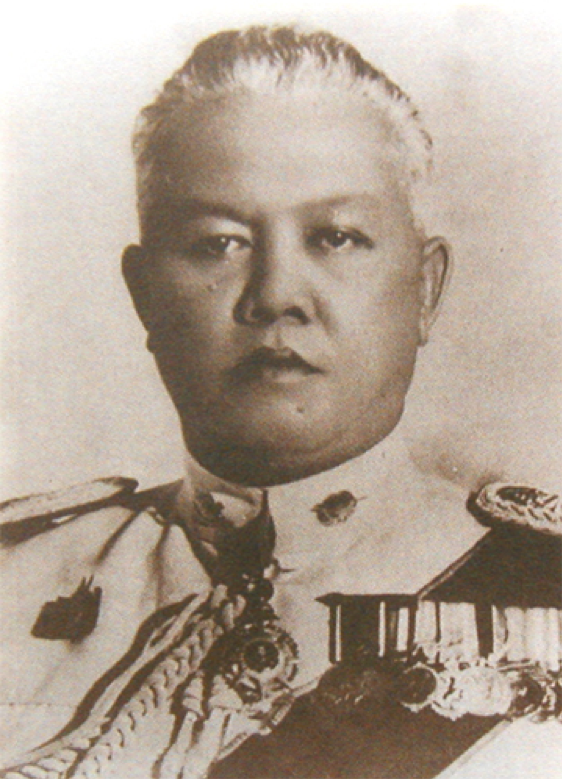

Phao Sriyanond: Police Chief (1951-57)

With the demise of Sarit, his deputies Gens. Thanom Kittikachorn and Praphat Charusatien succeeded him with the former as prime minister and the latter as army commander respectively. The man they selected as police chief was Gen. Prasert Rujirawong, a Sarit confidante. Prasert managed to insulate the police from army control while obtaining buoyant budgetary allocations. 1965 saw the creation of the Communist Suppression Operations Command (CSOC), later called the Internal Security Operations Command (ISOC), which was partially meant to hem in the police under army-led control. By 1970 Praphas and Prasert had become bitter bureaucratic foes. The 1971 army-supported coup was partly meant to weaken Prasert so that Praphas’s army could solidify control over the police. In 1972, upon Prasert’s retirement, Praphas followed Sarit’s example by taking on the additional post of police commander (as well as CSOC head and interior minister).

But 1973 revitalised independent police power. Praphat’s police deputy Gen. Prachuab Suntarangkul secretly collaborated with senior army officer Gen. Vitoon Yasawat as well as new Army Commander Gen. Krit Sivara in support of urban protestors that year. The result was the fall of Thanom and Praphas. Prachuab became police chief and Vitoon his deputy while Krit succeeded in dominating the army. Krit’s preference to make the army a passive force in the background allowed the police to grow as the principal security institution during Thailand’s 1973–76 period of civilian rule.

The sudden 1975 resignations of Prachuab and Vitoon as well Krit’s mysterious death in 1976 paved the way for a reactionary arch-royalist faction of officials to take control over the police. Two deputy police chiefs in particular— Monchai Pongponchuen and his deputy Narong Mahanon—were involved in ordering Border Patrol Police to massacre students at Thammasat University on 6 October 1976. Both later became police chiefs.

Serving as police commander from 1976 until 1981, Monchai took advantage of an uncommon period of extreme army factionalism as well as palace support to once again build up the police. But in 1981, following a bloody coup attempt, Prime Minister Gen. Prem Tinsulanonda purged several senior security officials, including Gen. Monchai. Under Prem, the army sought greater control over the police. This included the creation of a Capital Command in Bangkok and a Civilian-Police-Military Command-43 in the Deep South, both partially intended to keep the police under the army’s thumb. Prem then proceeded to implement reforms to demilitarise the police and clean up its corrupt image. However, by the time he left office in 1988, the proposed reforms remained stillborn.

Following the 1991 military coup, yet another effort unfolded to remove the police from under the Ministry of the Interior and formally subordinate it directly under the Ministry of Defence and the Armed Forces Supreme Headquarters. However, the junta was forced from power in May 1992, the Capital Command was abolished and the army again lost its control over Thailand’s police.

Prawit’s hold

From 1992 until 2001, civilian governments attempted various times to reform the police and bring it under accountable, transparent civilian control. Only in 1998 did the Chuan Leekpai government succeed in bringing the police out from under the control of the Ministry of the Interior and making it an independent governmental agency under the direct supervision of the prime minister. It was renamed the Royal Thai Police (RTP). The reform diminished the levels of bureaucracy between the prime minister and police, gave the prime minister closer monitoring authority over the police and diminished the clout of the Interior Ministry.

The 2001 landslide electoral victory of retired Police Lt. Colonel Thaksin Shinawatra brought to office a prime minister who sought to expand police power over the army perhaps more than ever before. Thaksin was intent on personalising control over the police and morphing it into a political agent of his prime ministerial authority. He tasked police with new responsibilities such as enhanced authority over issues of violence in Thailand’s Deep South and greatly increased the police budget (while reducing the army budget). A new 2004 Royal Thai Police Act gave police new responsibilities in assisting in national development projects, tasks which had previously been almost entirely assigned to the military. In addition, the law gave more power for the prime minister to influence police reshuffles. Under Thaksin, the police seemed to be evolving into a powerful security force not beholden to the army.

Thailand’s 2006 putsch stymied the rise of Thaksin over the RTP. However, though the incoming junta sought to weaken police power, a pro-Thaksin government was elected in December 2007 and returned to office in February 2008. It appointed Pol. Gen. Patcharawat Wongsuwan as Police Chief. Patcharawat is the younger brother of ex-army chief and current Deputy Prime Minister ret. Gen. Prawit Wongsuwan. At the time, Prawit was seen as close to Thaksin’s wife Pojaman Shinawatra and other pro-Thaksin politicians, while also acceptable to the military since he was the “father” of the Eastern Tigers faction indirectly dominating the army from 2007 until 2016. Patcharawat’s appointment enhanced the power of the Wongsuwan brothers over Thailand’s police for years to come.

Patcharawat Wongsuwan: Police Commissioner (2008-09)

At this point, palace elements sought to influence police promotions. Under Democrat Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva, Patharawat was succeeded in 2009 by Gen. Wichien Photposri in an acting capacity. Wichien is an arch-royalist who was close to the Queen’s Guard military faction and a friend of the Democrats. While the then-Queen reportedly favored Gen. Pratheep Thanprasert to succeed as police chief, her son preferred Gen. Chumpol Munmai. In the end, Wichien remained police commissioner in a permanent capacity.

The 2011 electoral victory of Pheu Thai’s Yingluck Shinawatra restored much of Thaksin’s political influence and also returned the police to a position of great influence. The police budget soared. Priewpan Damapong, the brother of Thaksin’s wife Pojaman, replaced Wichien as police chief, and a police general considered sympathetic to Thaksin, Adul Saengsingkaew, succeeded Wichien. Yingluck appointed former Commissioner-General of the RTP Kowit Wattana as her Interior Minister in 2011 and Pheu Thai also nominated a police general as its candidate in the 2013 Bangkok gubernatorial election. During the 2012–14 political crisis, Yingluck invoked the Internal Security Act and Emergency Decree but used police personnel instead of soldiers to enforce it.

Following the 2014 coup, the junta moved to cement army control over the police for once and for all. Military officials were given direct power over police. Decree 13/2559 bestows police powers under the Criminal Code and Criminal Procedures Code upon military officials, including military-directed paramilitaries, from the rank of sub-lieutenant and higher. The decree basically deputises soldiers as police, with the exception that it gives greater legal impunity to army officials as opposed to police. Such powers remain until today.

In his post-2014 role as deputy prime minister and deputy junta leader, Prawit Wongsuwan personalised his control over police promotions. Any suspected Thaksin sympathisers were immediately purged and replaced with his cronies. Adul was abruptly dismissed as police commissioner and replaced in acting capacity by Gen. Watcharapol Prasamrajkit.

Since 2015 Gen. Chakthip Chaijinda has served as police commissioner. Chakthip is close to right-wing firebrand Suthep Thaugsuban but is also a chum of Gens. Anupong Paochinda and Prayuth Chan-ocha as well as current Army Chief Gen. Apirat Kongsompong since their joint collaboration in quelling the 2010 redshirt demonstrations. But it is Chakthip’s tight association with Prawit and clear obeisance to the new King Rama X that has sustained him in power at the helm of the Thai police.

Below Chakthip in the police hierarchy, Prawit has succeeded in building up substantial influence since 2014 (see figure 1). In 2020, Prawit loyalists cover approximately 3 out of his 5 deputies, half of the 9 assistant police commissioners, 7 of the 9 police bureau chiefs, as well as the commander of the police-controlled paramilitary Border Patrol Police. One notable assistant not controlled by Prawit is the rapidly rising Gen. Permpun Chidchob, younger brother of political bigwig and Buriram United Football owner Newin Chidchob. The three prominent police factions in Thailand’s post-2019 lower house of Parliament are aligned with the three leading political parties: Prawit/Patcharawat/Chakthip with Phalang Pracharat, Chidchob with Bhumjai Thai, and Shinawatra/Damapong with Pheu Thai.

The palace and the police

The only powerful competitor to Prawit’s sway across the police has been the palace. Since the beginning of the new reign in 2016, there has been a gradual move towards the appointment of senior police favorable to the palace, irrespective of their sentiments towards Prawit. One such individual is Deputy Police Chief Gen. Suchart Teerasawat.

In October 2018, a special police division was established to protect the monarchy. Named the Ratchawallop Police Retainers, Kings Guard 904, it is directly controlled by the King and had previously been a protection unit for the then-Crown Prince. The unit’s commander, Maj. Gen. Torsak Sukvimol (as the Deputy Chief of the Central Investigation Bureau), is the younger brother of palace confidante Air Chief Marshal Sathitpong Sukwimol. Since 2018, Sathitpong has served as Director-General of the Crown Property Bureau and the Lord Chamberlain of the Royal Household Bureau.

The Ratchawallop Police Retainers enjoy almost limitless power since they are ambiguously charged with carrying out the King’s wishes. They have played a prominent role in cracking down on suspected regal opponents. In 2019, with the Police Retainers moved under the Rachawallop Royal Guards Command, the RTP’s Crime Suppression Division set up a new crack SWAT commando unit to replace it. Called the Hanuman Unit, its commander, ultra-arch-royalist Col. Vijak Darom is ascending rapidly in police promotions.

Perhaps the only recent “poster boy” in the RTP has been former Royal Thai Police Immigration Bureau Chief Lt. Gen Surachate (Big Joke) Hakparn, seen as close to Prawit. Big Joke made headlines for his highly publicised pursuit of foreigners illegally residing in Thailand and other related criminals. He also publicly touted the need for more transparency and less corruption among state officials. He sought to streamline the immigration process and shut down “VIP” lanes at major airports, diminishing the potential extortion of bribes.

Scrutinising Thailand’s 2019 annual military reshuffle

The annual military reshuffle shows a military leadership in transition.

Surachate (“Big Joke”) Hakparn, Police Immigration Bureau chief (2018-19)

Meanwhile, two police deputy commissioners (Veerachai and Chaiwat) were also dismissed abruptly from the royal police retainer corps and suddenly transferred to inactive civilian positions under the prime minister. The two were suspected of leaking a phone conversation between Veerachai and Commissioner Chakthip in which the latter criticised the former for defying his order not to personally supervise the investigation of Big Joke’s shot-up car. Though Chakthip is apparently not on good terms with Big Joke, Veerachai or Chaiwat, the three are perceived as being close to Prawit. Moreover Chakthip’s personal influence is not greater than that of the deputy prime minister.

A question thus arises as to who has enough power to push Prawit’s police loyalists into inactive positions. Only Thailand’s regal institution could be so influential.

In October 2020, Chakthip is set to retire as police commissioner and there are four likely successors. One is Deputy Commissioner Gen. Suchart Teerasawat, who graduated with Chakthip in police academy class 36. He is both neither particularly a Prawit man nor opposed by the palace. He retires in 2022. Second is Deputy Commissioner Gen. Nu Mekamaug, a Prawit man and graduate of class 38 who retires in 2021. Third is Inspector Gen. Chanasit Wattanawarangkul, another class 36 graduate and Chakthip chum, though he too retires in 2021. Finally there is Deputy Commissioner Suwat Jaengyaudsut, another class 36 graduate close to Chakthip who retires in 2022. If Suchart gets the job then it will likely demonstrate a lessening of Prawit’s influence in the police. Nu’s promotion (though less likely) would prove the opposite. The appointment of Chanasit or Suwat would be a middling choice.

Chakthip Chaijinda, Police Commissioner (2015-Present)

In the end, the Royal Thai Police has proven itself to be a partisan, corruption-tainted security institution which is a close second to the army in terms of manpower and budget. The army has tried time and again to keep the police under its sway but such attempts have always proven impossible to sustain. Over time, various police chiefs (or commissioners) have succeeded in constructing bureaucratic fiefdoms over the police. The latest person to do that has been Gen. Prawit Wongsuwan (who also dominated the Thai army from 2007 until 2016), through his brother Patcharawat and current police commissioner Chakthip. But nothing lasts forever. Prawit in 2020 is confronted by a palace intent on personalising its own control over the army—as well as the police.

Figure 1: Senior Officials of the Royal Thai Police (2019-2020)

| Position | Name | Pre-cadet class | Police class | Retires | Comment |

| Police Commissioner General | Chakthip Chaijinda | Vajiravudh College | 36 | 2020

(serving since 2015) |

Close to the Prawit and the highest institution |

| Deputy 1 | Veerachai Songmettha | 21 | 37 | 2021 | Transferred to an inactive post in PM’s Office in January 2020; Chanasit chosen to take over his tasks (close to Prawit) |

| Deputy 2 | Suchart Teerasawat | — | 36 | 2022 | Close to Chakthip and the highest institution |

| Deputy 3 | Chaiwat Kateworachai | 20 | 36 | 2020 | Transferred to an inactive post in Operations Centre in January 2020; Suwat chosen to take over his tasks (close to Prawit) |

| Deputy 4 | Nu Mekamaug | 21 | 38 | 2021 | Close to Prawit |

| Deputy 5 | Suwat Jaengyaudsut | 20 | 36 | 2022 | Close to Chakthip |

| Inspector General | Chanasit Wattanawarangkul | 21 | 36 | 2021 | Husband of ex-Tourism and Sports Minister; close to Chakthip |

| Assistant 1 | Sakda Chuenpakdi | 20 | 36 | 2020 | Close to Prawit |

| Assistant 2 | Wissanu Prasatong-osot | 21 | 37 | 2021 | |

| Assistant 3 | Natorn Paeowsuntorn | 21 | 37 | 2021 | Close to Prawit |

| Assistant 4 | Damrongsak Kittiprapat | 22 | 38 | 2022 | |

| Assistant 5 | Piya Utaiyo | 22 | 38 | 2022 | Close to Prawit but responsible for the King’s Chit Arsa program |

| Assistant 6 | Roy Impairot | 24 | 40 | 2024 | |

| Assistant 7 | Wichat Impaichit | 24 | 40 | 2024 | |

| Assistant 8 | Permpun Chidchob | — | 37 | 2021 | Younger brother of politician Newin Chidchob |

| Assistant 9 | Jaruwat Waisiya | 21 | 37 | 2021 | |

| Assistant 10 | Pongsawut Pongsri | 20 | 36 | 2020 | Close to Prawit |

| Metropolitan Police Headquarters | Pakpong Pongpetra | 22 | 38 | 2022 | Close to Prawit and Chakthip |

| Provincial Police Region 1 | Amporn Buarapon | 22 | 38 | 2022 | |

| Provincial Police Region 2 | Montri Yimyaem | — | 38 (class president) | 2022 | |

| Provincial Police Region 3 | Ponsak Prasersak | 19 | 35 | 2020 | Close to Prawit |

| Provincial Police Region 4 | Jaroenwit Sriwnich | — | 36 | 2021 | Close to Chakthip |

| Provincial Police Region 5 | Prachuab Wongsuk | — | 39 | 2023 | Close to Chakthip |

| Provincial Police Region 6 | Apichart Srisit | — | 36 | Close to Prawit | |

| Provincial Police Region 7 | Tana Chuwong | 28 | 42 | Close to Prawit | |

| Provincial Police Region 8 | Jirawat Tipyajanot | 20 | 36 | 2020 | Younger relative of ex-1st Army Chief Teppong Tipyajanot; close to Chakthip |

| Provincial Police Region 9 | Ronsin Busara | — | 36 | 2021 | Younger relative of Navy Admiral Dechadol Busara |

| Border Patrol Police | Vichit Paksa | 21 | 37 | 2021 | Close to Prawit |

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss