Like paintings, leaders evoke certain colours and styles to the optical presentation of themselves in the public imagination. Sukarno was blazing red, as red as one of the dogs in Agus Djaya’s Dunia Anjing (World of Dogs)—chaotic, symbolic, and impressionistic in his tone. Suharto was subtle orange-yellow, like the tiger in Raden Saleh’s painting—naturalistic, romantic, but brutish in essence. His strength was in evoking awe out of the tiger’s ability to dominate. Abdurahman Wahid was Affandi’s strokes of green—rough, bold, disruptive and progressive; the leader who tried to abolish the Indonesian parliament was indeed one of a kind. Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono was as blue as Basoeki Abdullah’s Roro Kidul (Queen of the Southern Sea)—nostalgic and mellow, embellishing the reality of his leadership of being more beautiful. But Joko Widodo’s (Jokowi) colour and style needed to be unpacked differently.

Raden Sarief Bustaman Saleh, Fight between a Javanese rhinoceros and two tigers, 1840. Oil on canvas, 48cm x 60cm. (Public domain)

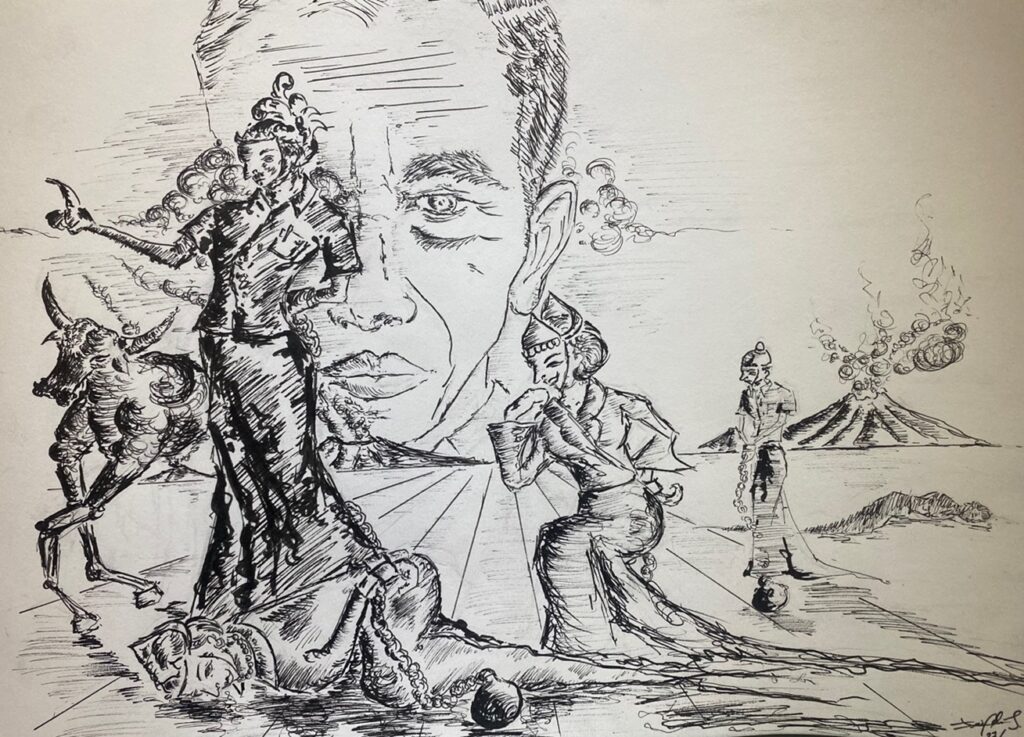

Jokowi’s optics conjured Yogyakarta’s surrealist painters, particularly Ivan Sagita. Surrealism embraces dream-like scenes and often displaces, distorts, or assembles ordinary objects in bizarre ways. Emerged in the early 1980s, Yogyakarta surrealism combines Western surrealist sensibilities with Eastern (mostly Javanese) social commentaries. Sagita’s work illustrates the struggle of Javans in navigating social hierarchy, not by preaching but by relying on the placement or displacement of carefully curated characters. Jokowi’s politics also relied on appointing and reshuffling political elites as an instrument to convey his intention.

The impossible conversation between Sagita and Jokowi is probably unintentional. Sagita and Jokowi were both educated in Yogyakarta, attuned to Javanese sociocultural norms, and able to appreciate the power behind subtleties. Sagita’s Manusia and Wayang (Men and Shadow Puppets) combined realism with an almost oppressive colour hue, hiding the message behind the messengers, the puppet from the puppeteers, and disruption behind the stability—-this sum up Jokowi’s leadership colour and styles.

Deconstructing Jokowi’s Colour

Ivan Sagita’s potency is not in the seen but in the unseen. The spirituality of his painting is presented by displaying the characters in uncomfortable positions, restraining their brilliance with the heaviness of his colour mixes. He often distorted faces, such as in Meraba Diri (Touching One Self), which connotes a journey to identity exploration. In the Wayang series, Sagita hides the faces behind shadow puppets’ masks. When he shows the faces of his characters, they are part of narrative device to convey specific emotions, not the dominant characters. Observers are often first forced to evaluate the characters and their placement before taking a step back to make sense of Sagita’s colour. Like Anish Kapoor and his blood red or Matt Rothko’s chapel of dark shades of blue and purple, Sagita’s colour obsession was also spiritual and socio-psychological. As he put it “Melihat kehidupan di lingkungan saya, saya mendapat kesan bahwa semua orang dikendalikan oleh kekuatan tak terlihat” [Observing life around me, I got this impression that everyone is controlled by an invisible force]. He smuggled himself into the cloud behind the characters, intensely dark because he blends his white to tone down other brilliant colours. In a way, in his painting, Sagita is everywhere but nowhere—an invisible force.

Like Sagita, Jokowi also is an invisible force. His colour cannot be seen, but felt. He is the white mixer that is hidden behind other colours, muting their hues and adding opacity. This is because in he relies on others to do his politics. When Jokowi reconveyed the empty idea of Global Maritime Fulcrum (a concept offered by his security team), Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi worked hard to translate what it meant. When Jokowi wanted more Islam, Retno ensured Islamic emphasis of Indonesian Foreign Policy was projected through a series of staged photo ops. When Jokowi wanted more culture in Indonesia’s foreign policy, Retno danced. Not only has this constant translation strengthened and cemented Retno’s position in Jokowi’s cabinet, but it also reinforces the importance of subordination to Jokowi’s hegemony: Jokowi has essentially restrained Retno’s colour.

Jokowi’s strength was to restrain and harness the colour of others. He surrounded himself with dominant personalities without making himself look small. He promised them power without surrendering his own, and he made them work for him. When Jokowi desired a strong maritime focus, Susi Pudjiastuti translated it into sinking ship policy. When he desired close cooperation with China, Defence Minister Prabowo Subianto (former opposition leader) switched his critical rhetoric against Beijing. When Jokowi uttered the ambition of realising investment projects and moving the capital from Jakarta to Nusantara, Minister of Finance Sri Mulyani could resist in a small way but still needed to think of how to make this idea possible. When Jokowi hinted at the idea of maybe having the third term, Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs and Investment Luhut Panjaitan started testing the waters. While the idea of ministers doing leaders’ bidding is not unfamiliar, Jokowi’s performance is often limited when it comes to the ability to put forward conceptual thinking or to speak in a foreign language, which begs the question which of the aforementioned ideas originated from him.

How to distinguish the message from the messengers?

Author’s illustration of Jokowi’s authority, inspired by Sagita’s Manusia dan Wayang.

Jokowi is a translational leader: he gathers ideas like a bird making a nest, according to which one is able to use to get him closer to his ideal of power. Every character is carefully curated to serve a purpose in Jokowi’s optical presentation of his leadership: Luhut is an image of strength, Sri Mulyani of intellect, Prabowo of taming an enemy, Susi of rebelliousness, and Retno of acquiescence; restraining these dominant characters is what makes Jokowi’s leadership.

Harnessing dominant personalities is an art Jokowi has mastered. However, managing them presents a delicate challenge, especially when they cannot help but be radiant. The elimination of Anies Baswedan in 2016 (then Minister of Education and Culture) and Gatot Nurmantyo in 2017 (then TNI chief); the marginalisation and eventual elimination of Susi in 2019; the demotion and promotion of Ignatius Jonan (demoted as Ministry of Transport to Minister for Energy in April 2016 and promoted as the Mineral Resources of Indonesia in October 2016), Andi Widjajanto (demoted from Cabinet Secretary in August 2015 and later promoted as the Governor of the National Resilience Institute in 2022), and Luhut, (demoted as Presidential Chief of Staff in September 2015 and climbing his way back up with his appointment as the Coordinating Minister of Maritime and Investment Affairs in July 2016); these were all example of his way to eliminate those who do not toe the line, or reflect a colour that he likes. This is not just a matter of harmony but also political order: although he is not the dominant colour, his position on top of the hierarchy must be preserved.

As Jokowi’s colour cannot stand by itself, he constantly needs to negotiate with other elites and bargain with them. Bargaining with oligarchs and balancing them against each other no longer becomes a tactic but raison d’etre. Like Sagita’s painting, the interaction between the character and choices of colour is how the painting conveys specific messages. However, there is the peril of co-dependency between Jokowi and others. When leaders depend on translation, they lose the ability to speak for themselves, as every idea is filtered through their subordinates’ opinions. As a result, a policy produced by such a leader is often incoherent lacks principles. Take the example of the infamous public discourse in mid-2019 between Susi’s environment-friendly position that prescribed limitations on unsustainable fishing practices and Luhut and Jusuf Kalla’s (his former vice president) pro-fisher policy that demanded deregulation. Jokowi’s absence of vision meant that he had no position in the debate, and the conflict resolution was based on whom he needed the most to advance his position. Luhut emerged as the winner not because Jokowi is inherently anti-environment or pro-fisher, but for political reasons.

Reconstructing Jokowi’s Leadership Style

Leadership style cannot be divorced from leaders’ visions of where they want the nation to move to and the desire to delineate themselves from their predecessor. In the early 1950s, Sukarno desired the Indonesian identity to be post-colonial, so he discredited those who painted in Western style and ushered in a hegemony of artists, including Agus Djaya, with a specific style whose paintings depicted local themes. In the early 1970s, Suharto departed from Sukarno’s Indonesianism and re-established the significance of Raden Saleh (a Javanese who painted in the European romantic style) within Indonesia’s cultural imagination, signalling that cooperation with the West was imperative to Indonesia’s identity. Like Saleh’s problematic history of complicity with the colonial power, Suharto coerced the nation to accept the brutality of his brush strokes in exchange for beauty.

Postage stamp issued in Indonesia, 1967, featuring a reproduction of Fight to Death by Raden Saleh. (Public domain)

In October 1967, marking the country-wide anti-communist pogrom, Saleh’s Fight to the Death painting was issued as a postage stamp to evoke the “justified” bestiality needed to eliminate communists. This was issued in tandem with a postage stamp of the Lubang Buaya monument, where the bodies of the officers executed by the Indonesian communist parties were thrown.

Jokowi’s style draws from Suharto’s desire for harmony but is inherently distinctive in his urges for disruption. The ability to understand their differences is like differentiating between Sagita’s and Saleh’s techniques: both painters were romantics from different genres. Similarly, while both presidents were willing to use authoritarian means to achieve their ends, Jokowi and Suharto are different political creatures.

Jokowi’s technique relies not on conveying beauty but on demonstrating progress, akin to Sagita’s subtle but disruptive style. Jokowi’s most original contribution is probably his vision of a post-Java Indonesia, which also distinguishes him from Suharto. Out of the seven Indonesian presidents, he is the one who has spent the most time in his presidency travelling around Indonesia, embodying different Indonesian cultures, focusing on investment outside Java, and embracing inter-island connectivity as part of his presidency. This has disrupted the dynamics sustained since the late Sukarno and early Suharto periods which located Java as the core and the rest as the periphery.

The underpinning politics between Jokowi and Prabowo reveals a deeper complexity within the Indonesian election.

Jokowi-Prabowo political reconciliation as Javanese strategy

Furthermore, if Suharto’s primary source of authority was fear, Jokowi relies on a subtler form of marginalisation: hegemonising the national discourse. Jokowi enlisted an army of social media buzzers and loyalists to engineer political narrative. Differing ways of generating authority also create distinctive approaches to how Suharto and Jokowi enlisted religion to control dissent. Suharto used religion as a tool for social control. During Suharto’s regime, the Indonesian military trained Islamic radicals as militias to reorder the social hierarchy, reinforcing the position of pribumi (native son) and Islam as the dominant groups. But Jokowi, like Sagita’s paintings, was more performative in his approach. Jokowi dressed up religiously, undermined Islamic factions that supported the opposition, appointed NU leader Ma’ruf Amin as his deputy, and rewarded NU with various economic benefits, all to bolster his chance of winning the election, but without the intention of revising social hierarchy as Suharto had.

Like the Yogyakartan surrealist, Jokowi’s leadership style offers a dreamscape: he relied much on the promise of the future. He often asked Indonesians to tolerate his unpopular policies: lowering oil subsidies, increasing taxes, disregarding bureaucracy, insisting on moving the capital, and insisting on white elephant projects such as the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway.

All these promises that we are moving forward into modernity as a nation. Unlike Yudhoyono’s subsidies that give fish to people, Jokowi takes away the fish, leaves behind the fishy smell, but promises that there will be a hot meal at the end.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss