The latest bombings and arson attacks in Thailand are most likely to be the actions of Malay insurgents or radical Red Shirts, writes Zachary Abuza.

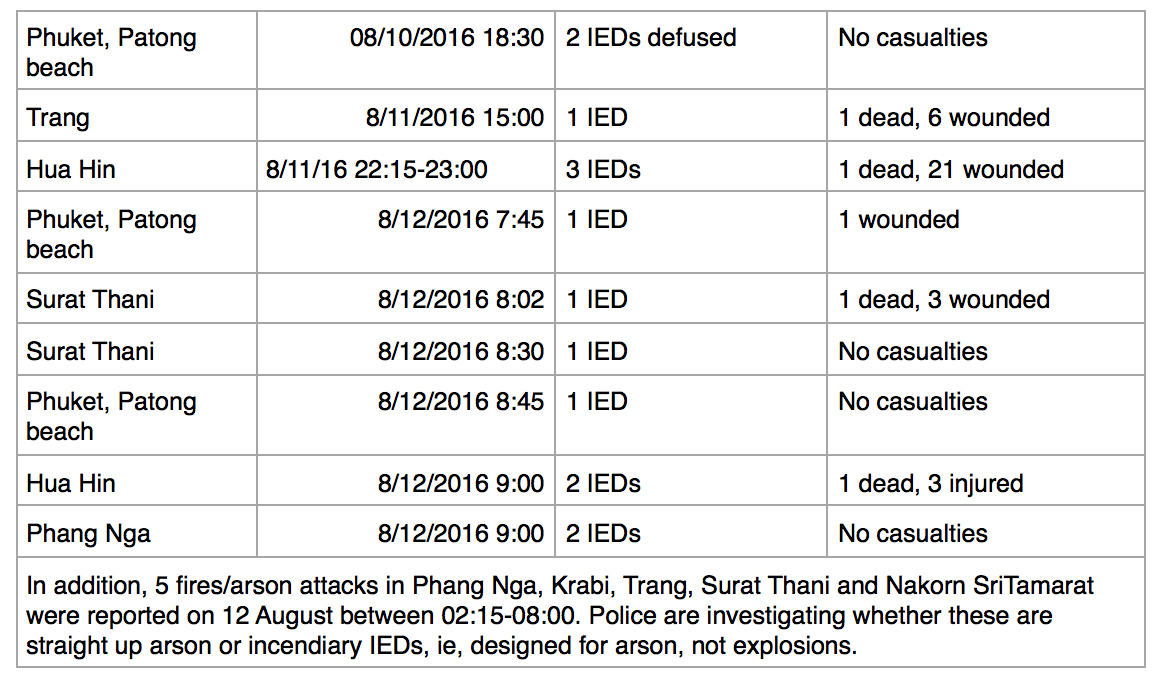

Between 10 and 12 August, Thailand was rocked by a string of 14 IED attacks across eight provinces in its upper south.

Four people were killed and 33 wounded, including 10 Western tourists. Authorities defused two of the 14 improvised explosive devices (IEDs) placed at the tourist destination on 10 August, but never made this public until after the other bombings. Police also found one other suspicious object, but have not commented on whether it was an IED. To date no one or group has claimed responsibility.

In addition, there were five separate suspicious fires — possibly arson attacks in Phang Nga, Krabi, Trang, Surat Thani and Nakorn Sri Thamarat that destroyed markets, a Tesco Lotus, and other buildings. Police are investigating whether these were straight up arsons or caused by incendiary IEDs, that are frequently seen in the south. All of these arsons occurred between 02:15 and 08:00 and intended to minimise casualties.

Many of the IEDs were “double tap”, going off in quick succession. And yet the casualty rate was relatively low. Four IEDs caused no casualties.

The IEDs were relatively small. Almost all were detonated by cell phones. While they are similar to IEDs found in Thailand’s Deep South, where an insurgency has been ongoing since 2004, that says nothing. There are only so many ways to make an IED, and the bomb-making plans are readily available online.

The five locales for the IEDs were tourist areas. But the size, design and placement of the devices was clearly not intended to maximise casualties. They were designed to send a message.

The question is from whom? There are plenty of suspects. There is no evidence that this was an external terrorist group, such as ISIS or even Uighur extremists responsible for the August 2015 Erawan Shrine bombing in Bangkok.

This was domestically orchestrated, which leaves two suspects: Malay insurgents or radical red shirts or other regime opponents. Both have their motives to discredit the military regime at this time.

Suspect one: Malay insurgents

The insurgency is now in its 13th year, and has reached a stalemate. Peace talks with the military are going absolutely no where. The goal of the Thai army is clearly to degrade the insurgency and get violence to a low enough level that they can attribute it to criminality, and thus have no need to make any meaningful concessions at the negotiating table.

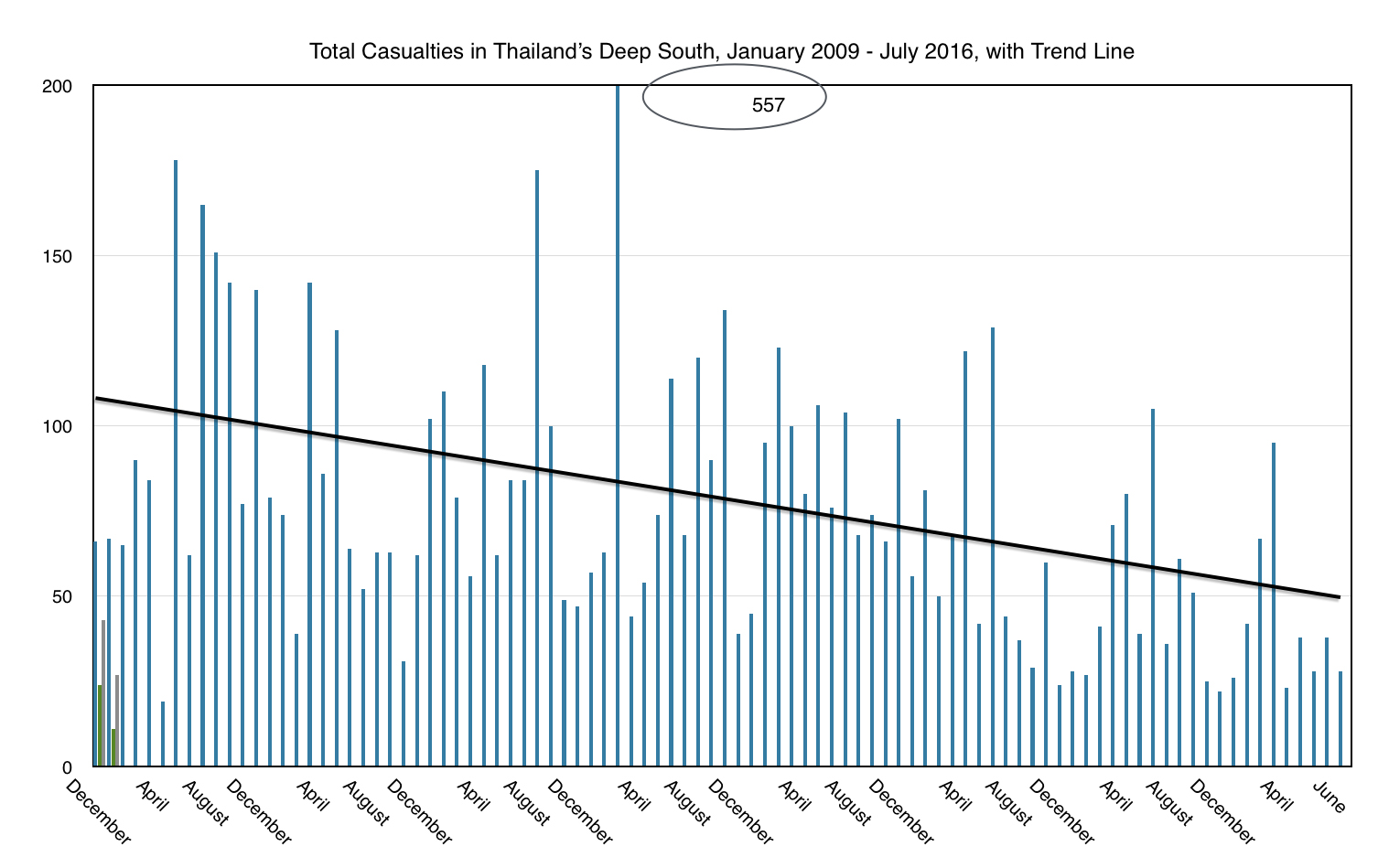

Violence in 2016 is clearly down, as it was in 2015. The average monthly death toll is currently just under 13, a third of what it was in 2009. Since the start of 2009, the monthly average number of casualties in the south has been 81. But since the May 2014 coup, it has fallen to 49.

It’s been years since the insurgents have been able to pull off large-scale coordinated attacks across multiple cities and provinces, and even when they have, its always been confined to the three-and-a-half provinces of the Deep South: Narathiwat, Yala, Pattani and parts of Songkhla. Out of area attacks such as Koh Samui in 2015 have been one-off attacks.

They do like to hit tourist venues, but they have been “out of area” while remaining “in area”. They hit tourist venues for Malaysians, such as Sungai Golok, Betong, Hat Yai, and Sadao, where there are few if any Westerners. These are all on the periphery of their claimed territory. And even attacks in these places have been quite limited. Insurgents are clearly aware that a major attack on a tourist venue would ultimately be counterproductive.

Technically the Malay insurgents have the capacity to do these attacks. Insurgents routinely use double tap IEDs, though in a more sophisticate away to target first responders. Insurgents, likewise, have never claimed responsibility for any attacks. The question is if they have the logistic ability to pull it off. While I have my doubts, it is worth noting that the extensive network of checkpoints in the Deep South could actually make out of area attacks easier to perpetrate.

I should note that much of the evidence regarding the bombings in Sadao, Betong, Hat Yai and Koh Samui suggest that these were carried out by hardline cells frustrated at either the pace and scope of the insurgency or the peace process itself.

The April 2015 Koh Samui bombing was clearly intended to send a signal, not kill people. The junta tried to false flag the attack on Red Shirts, and it was not until June 2015 that charges were actually filed against insurgents.

And with the peace talks stalled and the new charter that completely precludes any type of regional autonomy, there is plenty of reason to suspect some insurgents have decided that it is time to escalate the violence to get the junta’s attention. They have an incentive to remind the junta the costs to not negotiating.

The Deep South was one of only three regions that overwhelmingly rejected the charter in the referendum, in addition to the Red Shirt bastions in Issarn and the North. There is clearly antipathy for any continued military hold on power and their current policies towards the Malay region. Don’t forget that in the days before and of the referendum, there were 35 IEDs across the Deep South, a time of heightened security.

The junta blamed the fact that 60 per cent of the voters in the Deep South rejected the charter on the fact that they were “intimidated and pressured by the insurgency group.” The government was clueless that the charter gives no hope for devolution of power and autonomy, while pushing Buddhist nationalism on a community fighting for its identity.

If the attacks were perpetrated by the insurgents it would be both unprecedented and suggest a sharp shift in their strategy.

Suspect two: radical Red Shirts

There is also plenty of reason to suspect radical political opponents of the military regime. That the bombings occurred on the eve and day of the Queen’s birthday, a national holiday, seems designed to discredit the military, who have justified most everything they have done — as self serving as it usually is — in the name of defending the monarchy.

The military’s continued hold on power is, in their own words, necessary to maintain peace and security. Clearly the scope of bombings discredits them. It reiterates the concern that security forces are so focused on peaceful protestors and activists against the junta, that they have dropped the ball on thwarting bonafide security threats.

The location of the attacks is interesting for another reason. The upper south region voted in very high margins in the 7 August referendum for the draft charter that will perpetuate military rule indefinitely.

With the restrictions on campaigning against the referendum, including up to 10-year jail terms, restricting open discussion and coercing voters, the referendum was truly shambolic. And many radicals opposed to the military see no alternatives but extralegal means to challenge the military.

And that could explain the choice of targets. All the bombing locales were in tourist destinations. Yet, none of the bombs was really meant to kill a lot of people. Even the physical damage they did was limited, according to these photos. They were intended to do harm to the tourist economy.

The junta has convinced itself that its rule is legitimate following the referendum. That is something I would challenge, seeing that they only won 61 per cent of 55 per cent of the electorate who bothered to turn up — that is, only 34 per cent of possible votes. Most independent analysts see the charter as having done little to reconcile the country’s deep divisions.

But the junta remains very vulnerable in terms of their stewardship of the economy. Foreign direct investment plummeted last year and exports are anemic. The Wall Street Journal politely described the economy as “underperforming.”

Tourism accounts for 10 per cent of the economy and is a critical cash cow. Even among their core supporters, the junta’s economic management has been their achilles’ heel. The referendum has done little to convince the business community or international investors that it will be smooth sailing ahead.

So who did it?

I really don’t know. I could argue it either way as both groups have a clear motive. Thai authorities claim that they have two people in custody, linked to the first two defused IEDs in Phuket. But they have provided no additional information as yet.

It is important that we brace for another politically motivated and incompetent investigation, as we happened following the Erawan Shrine bombing, when a shocking number of leads went un-investigated. To this day, there are far more questions about that devastating attack than answers.

The junta is likely to follow suit this time around. As a junta spokesman said, “This is not a terrorist attack. It is just local sabotage that is restricted to limited areas and provinces.”

But the attacks do discredit the regime whose legitimacy is far shakier than they care to admit.

The junta seemed awfully smug after the referendum. These attacks are a reminder of how divisive the military really is, and how far they really need to go to address the deep cleavages with both political opponents of the regime, and ethnic Malay.

And while I am not sure who perpetrated the attacks, I am certain of one thing: the junta will likely double down in its divisive and self-serving policies, rather than address legitimate and core grievances of large sectors of society.

Zachary Abuza is a professor at the National War College where he focuses on Southeast Asian politics and security.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss