Discarding Dependent Origination, Returning to the Primary Source of the 12-Links (十二因缘) in Theravada Buddhism.

Eisel Mazard (大影), 2011.

This article broaches the Theravada Buddhist doctrine of “Dependent Origination”, also known by the Sanskrit moniker Pratītyasamutpāda and as the “12 links” or teaching of the “Twelve Nidānas”. The author deals with competing interpretations of the most ancient primary source texts in this tradition (i.e., as extant in the Pali canon) that have formed the basis for an array of religious traditions, both ancient and modern, throughout Buddhist Asia. The author’s conclusion is that many later sources have digressed from the basic theme and subject-matter of the original text, knowingly or unknowingly, and he here sets out some unpopular facts about one of Buddhist philosophy’s most popular doctrines.

§1.

Although commonly praised for its profundity, it is rare to find a clear answer to the question of what this famous tract of text supposed to be about: what is the thesis that the 12-links formula was meant to explain or support? I find the answer in the text itself (i.e., the passages of the Theravāda canon discussing the 12-links formula, variously called, “dependent origination”, “causal genesis”, etc., in English) and then find corollary support in comparing different contexts that present the formula within the Pali canon (i.e., passages making use of the same terms in different ways).

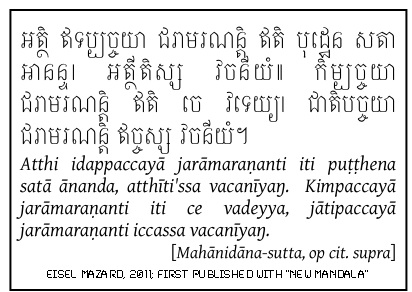

In the first few pages of the Mahānidāna-sutta, we have a prototypical version of the formula, in that the Buddha is explaining the way a monk ought to explain it.

Atthi idappaccayā jarāmaraṇanti iti puṭṭhena satā ānanda, atthīti’ssa vacanīyaŋ. Kimpaccayā[1] jarāmaraṇanti iti ce vadeyya, jātipaccayā jarāmaraṇanti iccassa vacanīyaŋ. [Mahānidāna-sutta, Cambodian canon vol. 16, p. 118, cf. PTS DN vol. 2, p. 55]

This is slightly more verbose than the most frequently found version of the 12-links formula (in list form), but the meaning does not differ from it: the sufferings of growing old and dying are predicated upon birth. The word for “birth” here (jāti) really does mean physical birth,[2] in the most obvious sense of the term; this can be affirmed both by comparing the use of the terms to other canonical contexts, and also (blatantly enough) within the Mahānidāna-sutta itself.

There are two suttas named Avijjāpaccaya[3] that specifically address an important misconception that could (and apparently did) arise from this mode of teaching about birth: evidently, ancient Buddhists were concerned that some might believe that the birth of the body was something separate from the birth of the living spirit. This is yet another facet of the orthodox defense against any doctrine of a “supernal self” or soul of any kind, found throughout the canon; the controversy (contrasting jīva to sarīra) makes it abundantly obvious that the subject-matter being born is a physical body (sarīra) —and that there was doctrinal concern that this would be misunderstood as excluding an un-mentioned life-force (jīva) that followers could presumed to be additional to the birth of the body, the arising of consciousness, and the other aspects mentioned in the 12-links formula. The mere existence of the controversy demonstrates that the subject being debated is indeed physical birth.

Within the Mahānidāna, we also have a brief gloss on the meaning of the word “birth”, making it clear that the term applies to any living thing in Buddhist cosmology (the text gives a range of examples: snakes, birds, four-footed animals, humans, and various gods and demi-gods) but this does affirm, once again, that the term for birth is meant in the obvious sense (even if birds are hatched from eggs, and even if the mode of birth pertaining to gods is unknown to us, there can hardly be any ambiguity about the meaning of the term in this context). Without birth, we are explicitly told, there would be no old age unto death, and the lesson is here left implicit that everything that is born must grow old and die (i.e., the gods and the snakes alike).

Given that the 12-links formula concludes with birth (and then various terms describing the suffering of life, growing old, and dying) the necessary conclusion is that the subject being described is a sequence of stages prior to birth. Contrary to the great bulk of English language interpretations (cf. §3, below) my thesis is simply that the 12-links formula concerns the development of the embryo, i.e., including the arising of consciousness in the womb. Conversely, the text is expressly not about the arising of consciousness is any other sense of the term(s). The consciousness described in this text indicates a stage of development that transpires inside the womb; this, too, may is stated (blatantly enough) within the Mahānidāna and may be affirmed from other contexts presenting the doctrine (if the terse wording of the formula itself leaves any doubt).

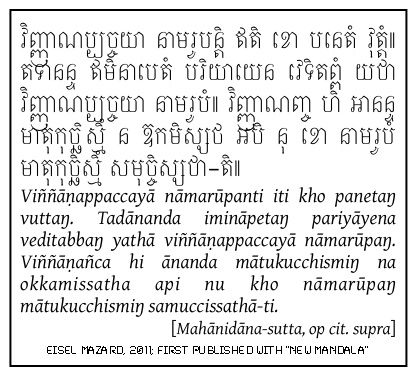

In the Mahānidāna’s brief gloss on the term nāmarūpa (discussed further below), we have a very explicit reminder that the subject-matter being described in this sequence of stages is the development of the embryo.

Viññāṇappaccayā[4] nāmarūpanti iti kho panetaŋ vuttaŋ. Tadānanda imināpetaŋ pariyāyena veditabbaŋ yathā viññāṇappaccayā nāmarūpaŋ. Viññāṇañca[5] hi ānanda mātukucchismiŋ na okkamissatha api nu kho nāmarūpaŋ mātukucchismiŋ samuccissathā[6]-ti. [Mahānidāna-sutta, Cambodian canon vol. 16 p. 133–134, cf. PTS DN vol. 2, p. 61–2.]

In the quotation, above, it is indisputably clear that we are reading about something that may (or may not) enter into (okkamissatha) the mother’s womb (mātukucchismiŋ). In my interpretation, this is consistent with the subject-matter of the paragraphs before and after, and is a natural (and unsurprising) part of the topic discussed in the text as a whole; however, the passage is wildly incongruent with attempts of many other interpreters to render the whole doctrine in more abstract terms (variously psychological or metaphysical).[7] In the last sentence of our quotation, above, we are told that once it is in the mother’s womb, it may (or may not) “consolidate” properly —according to the somewhat speculative translation of samuccissathā offered by Rhys-Davids & Stede (1925, s.v. samucchati, an entry that declares the “derivation and meaning uncertain”). I think it would not add much to digress into debating the meaning of samucchati in this context, but (given that the subject-matter is sexual reproduction) there could be an element of euphemism here that would be difficult to pin down with certainty. The rendering “consolidate” interprets the word as a composed of a prefix added onto a form of the verb mucchati (and, I note, the difference between cca and ccha is normally of etymological significance in Pali, obliging us to raise an eyebrow, even if this turns out to be correct); the latter can mean “to stiffen up”, perhaps in the sense of congealing, but perhaps in some other sense instead (Davids & Stede, 1925, s.v., mucchati, and cf. the usage of mucchatithroughout DN 25, the Udumbarika-sutta).

Even if we began from no other data but this short quotation, above, there would be a limited range of possible meanings for the term nāmarūpa: it is something that must properly “consolidate” in the mother’s womb in the next stage of development after the arrival of consciousness (viññāṇa) there. Within this range of possibilities, it seems obvious to me that we must accept some guidance from Jurewicz’s (2000) findings that the pre-Buddhist (Vedic) tradition already used terms like nāmarūpa in describing the (supernatural) origins of human life in the womb; this may have been an analogy that the authors of the Buddhist texts were aware of, or (at least) it is one that provides a useful precedent (and parallel) demonstration of much of the terminology (even if the early Buddhist authors worked in ignorance of the Vedas). In both of these traditions, there may be an aspect of euphemism (that would be difficult for a translator to fully disclose), but, even if so, the Pali text does not leave very much up to the imagination.

Conversely, if we were to disregard the fact that the development of consciousness transpires inside the womb, and is part of the description of an embryo, the whole purpose of the passage of text would disappear into abstract generalizations, regardless of the precise meaning assigned to nāmarūpa or samucchati.

§2.

In the context of ancient Indian literature, it is not surprising that some would ascribe a supernatural agency to the origin of consciousness in the womb, and we have evidence of this within the Pali canon. The Mahātaṇhāsaṅkhaya-sutta (MN #38, PTS MN vol. 1, p. 256 et seq.) provides a list of three factors that are pre-requisite for a woman’s fertility and conception of offspring (ibid. p. 265-6) —and one of them is the attendance or assistance of a type of demi-god. The Pali word is gandhabba, and this is a sort of “heavenly musician” that could be described as the masculine counterpart to a nymph: a sensuous and somewhat insouciant sort of sprite, often depicted as part of the entourage of the more powerful gods. There is no direct equivalent in the Greco-Roman pantheon; a gandhabba is not quite a satyr, nor quite a cupid.

The significance of this passage is controversial. A recent work kindly sent to me by the author, Richard Gombrich (2009, p. 73), simply stated that he has no explanation for it —i.e., because it is incompatible with the rest of our knowledge of the cycle of birth and rebirth in Buddhist cosmology and ethics.

This passage illuminates both the early Buddhist understanding of conception, and at least one misunderstanding that arose within the period of the canon’s composition and revision. I would explain it with comparative reference to a dialogue found elsewhere, in the Assalāyana-sutta (MN #93, PTS MN vol. 2, p. 147–8).[8] In the latter source, we find the same snippet of text concerning this type of demi-god being pre-requisite for a woman’s conception of a child, but here (instead of being a principle the Buddha himself is preaching) the gandhabba‘s role is one of the beliefs of (non-Buddhist) Brahmins that the Buddha is ridiculing in the context of a debate about caste purity and heredity. In addressing caste prejudice, the Buddha asks how the Brahmins know the caste of these demi-gods that they believe participate in the conception of their own children. The Brahmin proponent admits that he does not know the caste of these intercessory demi-gods (and it is interesting that the Brahmin implicitly presumes the caste system to extend up to the heavens). This is not the only sutta wherein the Buddha repudiates Brahmin notions of their own divine ancestry and special birthright with sexually explicit terms (cf. AN Soṇavaggo, Soṇa-sutta, PTS AN vol. 3, p. 221–222).

In the dialogue of the Assalāyana-sutta, the Brahmin replies that he does not know the caste status of these demi-gods that are supposed to be pre-requisite to conception, and we gain a useful contrast between pre-Buddhist and Buddhist assumptions about incarnation. In this context, it seems impossible that the demi-god could itself symbolize the looming spirit of an unborn person waiting to be reincarnated, though some modern Buddhists insist on this interpretation.[9] If this were the implied or symbolic meaning of the term, how could the Brahmin possibly be in doubt as to the caste-identity of a member of his own clan being re-born? Apart from the fact that the meaning of the word as a demi-god is attested throughout the Pali canon, and has cognates throughout ancient Indian literature in other languages (and in statuary, etc., generally), in this specific context we may insist that the word gandhabba cannot mean the spirit of one of the Brahmin’s own ancestors (awaiting rebirth as one of their descendants) because, if that were the meaning of the term, the Brahmin would be sure of the spirit’s case identity. Instead, the entire scenario provides us with a glimpse of a pre-Buddhist model of incarnation that can be contrasted to the 12-links formula, wherein the role of the gandhabba would seem to be exactly what the text describes: a demi-god that enables fertility. As with many forms of mythology, I cannot deny that there may be an element of poetic allusion or euphemism here; conversely, there is no reason to preclude the possibility that this myth indicates a traditional belief in a form of divine agency in conception, with no innuendo.

This type of myth would hardly be surprising in any cultural context (ancient India least of all). Whereas the Assalāyana-sutta contrasts the Brahmin belief to the Buddhist teaching, the Mahātaṇhāsaṅkhaya-sutta seems to conflate the two. In finding this Brahmin belief that divine intercession is a precondition for a successful pregnancy re-stated (without the context of the debate with the Brahmin) in the Mahātaṇhāsaṅkhaya-sutta, we are observing the cultural assumptions from one context “seeping into” the interpretation 12-links formula in the other. Even so, this misunderstanding still affirms that the early redactors of the text regarded the 12-links as an account of the arising of consciousness in the womb (and thus they did not regard the statement of this demigod’s role in fertility as “out of place” in an explanation of the 12-links formula). Conversely, for modern interpreters who seek to re-invent the meaning of the 12-links formula (as a sort of metaphysics) it must be difficult to account for such explicit references to a woman’s physical fertility that occur both within the formula, and in the canonical explanations surrounding it, in the most ancient canonical texts.

§3.

This essay has for its purpose the simple but fundamental task of establishing what the 12-links formula is about (i.e., the subject matter broached in the canonical primary source texts). I would now contrast a few of the popular opinions on this matter, taking my motto from Charles Darwin’s Descent of Man: “False facts are highly injurious … for they often endure long; but false views… do little harm, for every one takes a salutary pleasure in proving their falseness…”.

Many of the leading interpretations are pointedly vague. The influential translator Bhikkhu Bodhi remarks: “In its abstract form the principle of dependent arising is equivalent to the law of the conditioned genesis of phenomena.” (Bodhi, 1980, q.v. exposition, 2nd paragraph) As anodyne as this may sound, I must repudiate it as a “false fact”: the subject of the doctrine is simply incarnation (inclusive of conception, the development of the embryo, and birth). While this may extend to include the hatching of snakes and the births of gods and demi-gods (as shown above, §1), the primary concern of the text is human life in its tangible form. The text is not about the origin of “phenomena” (neither in its dictionary denotation, nor in any other sense of the term I can construe here); I would reject any attempt to broaden the meaning of this particular set of source texts into an abstract statement on epistemology or metaphysics. The Pali canon contains many discourses concerning the function of the mind and perception, but this isn’t one of them. A huge bulk of pseudo-philosophical hyperbole written by modern authors must collapse on this simple point: the original text does not broach the subject of the “structural relatedness of phenomena” (as Bodhi puts it, idem. 7th paragraph).

Although it would be ironic to look for a first cause on this subject, I would draw attention to Mrs. C.A.F. Rhys-Davids (1922, p. xiv) who confessed that her own interpretation of the 12-Links Formula (that has now inspired an amazing array of European theories) came from a spiritual experience that she had when reading the earlier work of Eugene Burnouf (ca. 1826) —and the latter theory was not even based on the Pali text.[10] Mrs. Rhys-Davids was among the first to set to work on the primary source concerned, but she did not approach the evidence with an open mind; instead, she sought to validate an earlier assumption. Having formed this expectation, she was very disappointed, she tells us openly, with what she found when she finally came to translate the original Buddhist text; however, despite what she saw as the deficiency of the primary source, she says that she did her best to emulate the earlier interpretation of Eugene Burnouf (ibid.). As is typical of her writing, she also directs insults, in passing, to the Buddhist monks whom she assumes have corrupted the texts —based on her own notions of what the Buddha’s teaching was originally supposed to be, with all evidence to the contrary dismissed as a later accretion.

These same attitudes are written into the PTS dictionary itself. In the entry forsaṅkhāra we are told:

None of the “links” in the [“dependent origination” formula] meant to the people that which it meant or was supposed to mean in the subtle and schematic philosophy (dhammā duddasā nipuṇā!) of the dogmatists. [Rhys-Davids & Stede, 1925, s.v., saṅkhāra]

Apart from the fact that this “definition” is openly contemptuous of its sources, and actually contains an insult directed to the texts’ authors, the combined effect of these PTS editions creates a loop of self-justifying references with no independent referent. If you doubt the interpretation of the translator, you can look it up in the dictionary (where you will find coeval justifications, with correlating attitudes of contempt for the primary sources they have selectively consulted).

The PTS-derived interpretations were excoriated by Nyanatiloka (1957, p. 157 & 161 et seq.); the latter correctly identifies Burnouf among the sources of these theories, and also vaguely blames “Theosophists” without naming C.A.F. Rhys-Davids (i.e., herself a Theosophist, and probably one of the intended targets of the criticism).

Nyanatiloka, for his part in this controversy, sets himself up as the defender of the commentarial tradition that extends the 12-links from a description of a single incarnation into a description of the causes and effects of reincarnation in three separate lifetimes. As such, the commentaries preserve what I would call a traditional misinterpretation of the 12-links formula, and it is one of much later origin than any of the evidence in the canonical accounts (with no resemblance to the diversity amongst the sources reviewed in §1 and §2, above).

In the context of Buddhist doctrine, the three-incarnations interpretation may seem like a very anodyne assertion, and yet I must disagree with it as another false fact. There are numerous texts dealing with the themes Nyanatiloka describes under this heading (i.e., of actions in a past life having effects at present, or of present deeds having effects in future incarnations) but the 12-links formula simply is not one of them. The original text describes a single birth only.

There is an interesting affirmation that the 12-links formula was originally understood as a single human incarnation in the Upanisa-sutta (PTS SN vol. 2, p. 29 et seq.; cf. Bodhi, 1980). The Upanisa-sutta is unusual in providing a bridge from the 12th link to the Buddhist practice leading to emancipation (thus, offering us a more upbeat sermon than the usual pattern, concluding with growing old and suffering unto death). This provides the reader with an obverse set of 12 stages leading from suffering (dukkha) to salvation (nibbāna). It makes sense (blatantly enough) that the Upanisa-suttapresents the formation of the embryo, then birth, followed by a life of suffering, in the middle of its expanded sequence of 24 (with salvation at the end); it would be impossible to make sense of the sequence if the first 12 links were (implicitly) divided into three separate lifetimes. It is completely consistent with Theravada orthodoxy in that nibbāna is here presented at the end of a series of stages that can be accomplished within a single lifetime; however, the text absolutely requires that its authors understood the original 12-links formula as the stages of a single incarnation for the two halves of this formula to fit together in this context.

While I regard the three-lifetimes interpretation (supported by Nyanatiloka) as incorrect, it deserves some credit for remaining thematically related to the original meaning of the primary source text (whereas many modern interpretations have digressed wildly from it). In a lecture on this subject, Nyanatiloka repeatedly refers to the subject-matter of the 12-links discussed as something transpiring inside the womb, also using the term “prenatal”. (Nyanatiloka, 1994, 3rd lecture) Apparently this has been less influential than the same author’s schematic overview of the terms in Nyanatiloka, 1957 (s.v. paṭicca-samuppāda) —a source cited in many of the more nebulous glosses on the issue, as if it adequately encompassed Nyanatiloka’s conclusions on the subject.

The three-lifetimes analysis is taken much further into the realm of abstraction and hyperbole by Mahāsī Sayadaw, a 20th century monastic innovator whose influence has already been institutionalized in an international group of meditation centers. However, Mahāsī’s interpretation does intermittently (if inconsistently) confess that the subject-matter being dealt with in the primary source text is the development of the embryo (2008, p. 39-41). In opening his discussion, he makes an important admission that is subsequently obscured:

…the Bodhisatta’s reflection was confined to the interdependence of mind and matter. In other words, he reflected on the correlation between consciousness [viññāṇa] and mind and matter [nāmarūpa], leaving out of account the former’s relationship to past existence. [Mahāsī, 2008, p. 2]

This is, in fact, a confession that the three-lifetimes interpretation is not supported by the primary source texts: there is no discussion of a past (nor future) existence internal to the 12-links formula, and Mahāsī was evidently aware of this (in examining the same text about consciousness and nāmarūpa within the womb, etc., ibid. p. 39-41); he is nevertheless willing to pretend that information to the contrary (based on later commentarial traditions) was implicitly intended by the Buddha but “left out” of the text. He proceeds to author an entire book on the premise that material the Buddha had “left out” (i.e., did not say) could be discussed as if were present where it is (in fact) absent. The result of this tactic is that a coherent account of a single incarnation (from conception through birth and death) becomes an incoherent account of three lives, omitting the significant stages of birth and death for all except the third, set in the future (ibid., p. 149-50).

§4.

As the argument, so far, has traded in certainties, there is hardly any need to draw conclusions. I would instead fill up a little bit of paper with some speculations of my own. In the course of the foregoing discussion, some may have wanted to know why the term nāmarūpa appears in the context of the 12-links formula at all, or, in effect, some may question how my interpretation can be reconciled with the denotation ofnāma and rūpa where they appear as two separate words in canonical usage.

In the study of any language, we must read usage in context: etymology can be misleading and, not infrequently, the two components of a word cannot tell us the meaning of the sum. In English, we can hardly construe any link between the meaning of the verb “hypostatize” and “hypo-stasis”; if regarded as two parts, the latter would seem to mean “under-standing”. The same principle can be illustrated by our English verb “understand”: it certainly does not mean “to stand under”, and cannot be analyzed into two halves. Complaints that this compound word, nāmarūpa, should have a meaning that is self-evident from the addition of one half to the other are founded on an assumption that is false, even if it may be appealing to the imagination.

Whatever nāmarūpa may be, it appears at one of the earliest stages of the conception and development of the embryo, and it is immediately subsequent to consciousness “entering into the mother’s womb”. Whereas the womb that consciousness “enters into” is specified as the mother’s, we have no indication of whose nāmarūpa it is that we’re discussing, and the two appear in mutual contrast, suggesting to my mind that the father’s role in reproduction must be accounted for somewhere in the equation. If we reject the possibility that nāmarūpa is imparted by the father, there would be remarkably little role for the male of the species in this traditional account of reproduction, and no clear “link” to the father’s hereditary characteristics.

The (empirically obvious) inheritance of a father’s traits in the next generation (of humans or any other creatures) is something that Buddhist orthodoxy needed to account for carefully, because the father’s own consciousness or spirit could not be construed to continue in his offspring. In other words, because “reincarnation” itself is never hereditary in the Theravada paradigm (and because it is of doctrinal importance that there is no soul that passes from father to son, and no continuity of consciousness between the generations) the description of other hereditary characteristics (such as physical appearances) becomes problematic and needs to be precise.

It is possible that the “name” suggested by nāma in this context had only a non-specific sense (related to personal identity) but the terminology could reflect an ancient belief in the patronym as something imparted to the embryo prior to birth. As a cultural assumption, the name, like the appearance, could be inherited from the father; or, of course, it could be presumed to be a gift from the gods. India has a diverse culture of magical naming practices, but the only evidence that is (without dispute) historically antecedent to the Pali canon would be found in the Vedas (already compared to the 12-links formula by Jurewicz, 2000).

It is not surprising that the canon preserves fragments of further debate concerning exactly whose consciousness shows up in the womb, and about the mechanics of incarnation and heredity in general. The debate of the Mahātaṇhāsaṅkhaya-sutta (MN #38) is consistent with the interpretation I’ve offered throughout this essay, and also reflects uncertainty (amongst ancient Buddhists) about the same issues that here seem to remain ambiguous in the original source text. In this debate, significantly, the problem of the continuity of consciousness between incarnations is explained with reference to the Buddhist theory of “the four foods”, a subject that has attracted much less scholarly interest than the 12-links formula.

As has been explained (§1, above) the inclusion of a special role for a demi-god (gandhabba) facilitating conception further “fills in the blanks”, but it seems to have been a pre-Buddhist notion that (in at least one context) the Buddha refuted in debate with a Brahmin; however, the inclusion of this notion in the Mahātaṇhāsaṅkhaya-sutta‘s account shows that the redactors of the texts were trying to provide a full and coherent account of fertility, conception, and the development of the embryo unto birth (with old age and suffering-unto-death being the next, and final, link thereafter).

In the more ancient context of the Vedas, there were other concepts of divine and magical agency involved in a comparable process of fertility, conception, and reincarnation, with comparable terminology, but I leave the discussion of that to Vedic scholars, such as Jurewicz (op. cit.).

The paragraphs above (§4) are somewhat speculative; I hope that the concrete argument presented in earlier sections of this essay will not be disregarded on this account.

My conclusion is, simply, that the 12-links formula is unambiguously an ancient tract that was originally written on the subject of the conception and development of the embryo, as a sequence of stages prior to birth; in examining the primary source text, this is as blatant today as it was over two thousand years ago, despite some very interesting misinterpretations that have arisen in the centuries in-between.

A Note on the Pali Text Used in this Article.

The text quoted here is based on a comparative reading of the Cambodian edition (wherein the DN was first published in B.E. 2501-2503, with succeeding volumes of the suttas in successive years) and the Sri Lanka Triptiaka Project’s e-text (SLTP). The latter is based on a comparative reading of the bilingual Sinhalese edition (BJT) and the Pali Text Society (PTS) editions. The Cambodian edition is itself based on a comparative reading of Cambodian and Thai manuscript sources with the earlier PTS editions. Variations from the PTS are footnoted throughout the Cambodian edition. My thanks are owed to the volunteers at the SLTP, and also to the Japanese charity (now known as the Shanti Volunteer Association) that supported the (post-war) reprinting of the Cambodian edition. The latter volumes do not have conventional publication data, and are normally cited as published by the Buddhist Institute, Phnom Penh.

Bibliography

Anālayo (Bhikkhu Anālayo), n.d., “Rebirth and the Gandhabbha”. Source unknown (unpublished essay or lecture?).

Bodhi (Bhikkhu Bodhi). 1980. Transcendental Dependent Arising: A Translation and Exposition of the Upanisa Sutta. The Wheel [Series] No. 277, Buddhist Publication Society, Sri Lanka.

Gombrich, Richard. 2009. What the Buddha Thought. Equinox Press: London.

Jurewicz, Johanna. 2000. “Playing with Fire”, JPTS XXVI, 2000, p, 77-103.

Jurewicz, Johanna. 2007. “The Fiery Self. The Rgvedic Roots of the Upaniṣadic Concept of Ātman”, in: Teaching on India in Central and Eastern Europe, Danuta Stasik & Anna Trynkowska (editors), p. 123-137.

Jurewicz, Johanna. No date (circa 2008?). “The R̥gveda, ‘small scale’ societies and rebirth eschatology”. A lecture delivered at the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studes, archived online at: www.ocbs.org/content/view/63/121

Mahāsī (Mahāsī Sayādaw) & U Aye Maung, translator. 2008 (1st ed. 1982). A Discourse on Dependent Origination. Association for Insight Meditation: Middlesex, England. [Available as an e-text, via www.aimwell.com]

Nyanatiloka. 1956. Manual of Buddhist Terms and Doctrines. Frewin & Co., Columbo, Sri Lanka. (This book has been through numerous subsequent editions, including widely-distributed reprints financed by the Taiwanese Corporate Body of the Buddha Foundation.)

Nyanatiloka (Nyanatiloka Mahathera). 1957 (the text of the expanded 2nd edition dates to 1957, the 1st edition to 1938, with numerous reprints in recent decades). Guide Through the Abhidhamma Piṭaka. Buddhist Publication Society: Kandy, Sri Lanka.

Nyanatiloka (Nyanatiloka Mahathera). 1994. Fundamentals of Buddhism: Four Lectures. The Wheel [series] No. 394–396. Buddhist Publication Society, Sri Lanka.

Piyadassi (Piyadassi Thera). 2008. Dependent Origination (Paṭicca Samuppāda). The Wheel [Series] No. 15, Buddhist Publication Society, Sri Lanka.

Rhys Davids, C.A.F.. 1922. The Book of the Kindred Sayings, vol. 2. Pali Text Society: Oxford.

Rhys-Davids, T.W. & William Stede. 1925 (1st edition 1921-23). Pāli-English Dictionary. Consulted (i) as an electronic resource distributed by the University of Chicago and (ii) as reprinted, 1989, by Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers: New Delhi.

Yuyama, Akira. 2000. Eugene Burnouf: The Background to his Research into the Lotus Sutra. The International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology. Soka University: Tokyo.

[1]. The Khmer edition has kiŋpaccayā throughout (កិំបច្ចយា vs. កិម្បច្ចយា).

[2]. I am here omitting to mention that there are interpretations that presume (and preach) the very opposite, most famously the 20th century Thai monk Buddhadasa.

[3]. SN, Abhisamaya Saŋyutta, Kaḷārakhattiyavaggo; PTS SN vol. 2, p. 60-63.

[4]. A variation of no significance: I am retaining the Khmer edition’s double-p spelling (vs. viññāṇapaccayā).

[5]. Again, a variant of no significance, I’m opting to retain the euphonic ñ of the Khmer version (vs. viññāṇaŋ ca).

[6]. The Khmer version has samuccijjissathā (សមុច្ចិជ្ជិស្សថា), footnoting the spelling above from the PTS edition.

[7]. In the interpretation of Piyadassi, 2008, glossing this particular “link” seems to interrupt his (exceedingly abstract) sermon as a non-sequitor, as he admits that the subject matter being discussed is (or at least includes), “…the conascent material body in its first embryonic stage…”. There is an obvious problem for an interpreter to admit that this is the subject-matter in the transition between two of the twelve links (viññāṇa& nāmarūpa) but not to confess it in the others, or to omit to mention that is the subject of the text as a whole. Piyadassi, 2008, q.v. section IV, second paragraph & section XI, first paragraph.

[8]. All of my observations on the gandhabba originate in a discussion (by e-mail) with Dr. Ole Pind, and to him my thanks are owed, for his patience and encouragement. I gathered my thoughts on the matter together and sent them off in reply to Gombrich (2009, p. 73, as aforementioned). I then received a reply from the Reverend Nyanatusita (of Kandy, Sri Lanka) who drew my attention to an undated (and apparently unpublished) article by a monk named Anālayo, titled “Rebirth and theGandhabbha“. This affirms that I am not the first person to notice the comparison between these two sources, nor am I the first to propose the Assalāyana-sutta as an explanatory origin for the role of the gandhabba. However, Anālayo seems to state his conclusion with some ambivalence, and his interest in pursuing the issue may be perpendicular to my own: “It may be from this original intent of the discussion of the three conditions for conception in the Assalāyana-sutta references to this presentation in other discourses and later works originated.” (Anālayo, n.d., p. 98)

[9]. This misinterpretation is foisted onto the source text in the translation of the MN by Sister Upalavanna, n.d., distributed on the internet by the Sri Lanka Tripitaka Project (metta.lk); her hermeneutic ploy is simply to provide the English phrase “the one to be born” as if it were a synonym for the gandhabba, described above, with no explanation.

[10]. For a study that includes some detailed discussion of the manuscripts that Burnouf had in hand, along with other sources and influences, see Yuyama, 2000.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss