Image: NamViet News

https://namvietnews.wordpress.com/

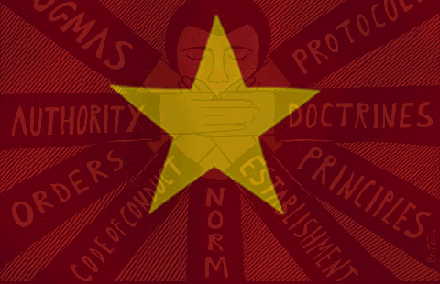

Faced with growing social media and Internet access, Vietnam’s leaders are further clamping down on media. But it may just backfire.

Vietnam’s National Assembly 10th Session, which opened on 20 October, is almost coming to a close with 18 bills deliberated during the 31-day period.

The most controversial is the draft Media Law, which is likely to spark heated debate and plenty of lobbying ahead of next year’s 12th Congress of the Vietnam Communist Party (VCP). The draft law has six chapters and 59 articles, including 29 amended articles from the exiting law.

In September 2015, the government announced plans for a sweeping overhaul of the state-owned media sector. The plan would lead to the consolidation of media and the loss of some 10,000 jobs. The draft law would restrict the power of state and provincial entities to have their own media organs and all media would be placed firmly under the control of VCP committees.

What’s driving the passage of the bill?

Deputy Minister of Information and Communications Tr╞░╞бng Minh Tuс║еn said that the impetus was “efficiency.” Nonsense. The reason is control.

Despite the fact that there is no independent media in Vietnam, the 1,100 media organs articulate a range of views and interests.

Party conservatives are concerned that the sheer number of media organs has led to “commercialisation.” Having lost their government subsidies, they need to turn a profit. They have done this by pandering to the masses with “sensational, sex, and slushy (3S)” stories or by being aggressive in their reporting, often times exceeding the bounds of what is permissible.

Although Government Decree 159/2013/N─Р-CP, issued in November 2013, shifted the responsibility for media organs to police themselves when it came to “3S” content, market forces and competition insured that they did not. The Army’s lamented daily that this has led to “affecting negatively public opinions.”

The sheer number of media and proliferation of social media sites makes it increasingly impossible for the Ministry of Public Security and the VCP’s Ideology and Propaganda Committee to maintain adequate checks, controls and monitoring.

In fact, they seem to have been caught surprised by the aggressive reporting of one newspaper, Ng╞░с╗Эi cao tuс╗Хi, and went to the extreme measure of not just arresting the editor, but shutting the entire paper down in February 2015. Several other editors and journalists have recently been sacked or reassigned.

The bill increases control through a host of new oversight, further pressure on editors, control over personnel, and annual licensing. The bill spells out a range of punishments for content violation.

The bill also reflect conservatives’ wariness of regionalism, by restricting the rights of municipalities or provincial level departments to have their own print media. And many other departments and official organisations, such as religions, will only be allowed to publish monthly magazines. The law limits the scope of reporting for specific media, increased restrictions on subject matter, and imposes further limits on foreign content.

Much of the remaining media will report to higher-level VCP authorities. For example, Tuс╗Хi Trс║╗, one of the two leading reformist newspapers, is technically the media arm of the Hс╗У Ch├н Minh City Communist Youth League. Under the draft law, it will be “put under a higher management level,” ie the Hс╗У Ch├н Minh City Party Committee whose chairman sits on the Politburo. The next HCMC party chief is rumored to be the current Minister of Public Security, Trс║зn ─Рс║бi Quang.

At the same time, established media organs firmly under the control of central government and party organs, including Vietnam News Agency, Voice of Vietnam radio, Vietnam Television, the Vietnam Defense Television channel, and newspapers Nh├вn D├вn (The People), B├бo Qu├вn ─Сс╗Щi nh├вn d├вn (People’s Army), and B├бo C├┤ng an nh├вn d├вn ─Сiс╗Зn tс╗н (People’s Public Security), will be expanded into multimedia platforms.

The need for multi-media platforms is all too apparent as Vietnamese, with soaring 3G (and soon 4G) usage, and Internet penetration (48 per cent nationwide and far higher in the cities) are turning to social media for their news.

Vietnam continues to have the most controlled Internet in Southeast Asia, with the greatest control over content and violation of user rights. While the government tries to crackdown on illegal social media, such as with the October closure of an underground online news channel and the arrest of its seven staff members, the technology is too available and there are too many workarounds.

The draft law is expected to meet broad resistance from the media, already chafing at censorship and controls. But more importantly it seems bound to fail. It is out of step with reality, technology, and public interest.

Perhaps more interesting than the details of the bill itself, are the personalities and politics behind it.

In 2014, conservatives were raising the alarm that too much political and economic decision- making had been devolved to technocrats in the government, away from party organs.

Conservatives rallied behind ─Рinh Thế Huynh to become the next General Secretary. As the head of the Central Committee’s Propaganda and Education Commission, Chairman of the Central Council on Political Thought, and member of the VCP Secretariat, he is the VCP’s leading ideologue.

He is also one of only six of 16 members who is eligible for re-election on the 12th Politburo without getting an age waiver. In 2014 and early 2015, Huynh actively campaigned around the country, with calls to reassert the authority of party organs.

And yet, it appears that the conservatives have lost many key battles. Politics remain opaque and there have been few leaks regarding the leadership selection at the Central Committee’s recently concluded 12th Plenum. But the Draft Political Report puts forth a vision of greater economic reform and integration with the West. Proponents of such a strategy seem poised to come out on top in 2016.

Party control over the media seems to be Huynh’s and fellow conservatives’ last stand. As Huynh holds only party positions and does not sit in the National Assembly, the legislation was formally proposed by Minister of Information and Communications Nguyс╗Еn Bс║пc Son, who is Huynh’s deputy on the Central Committee’s Propaganda and Education Commission, and also an advocate of greater party control.

Yet, the Ministry of Information and Communication is under the purview of Deputy Prime Minister V┼й ─Рс╗йc ─Рam, one of the leading economic reformers aligned with Prime Minister Nguyс╗Еn Tс║еn D┼йng. Young, media savvy, and Western educated, he’s the last person one would expect to endorse the law. And yet, his portfolio as Deputy Prime Minister includes social and cultural affairs. Having ─Рam push through the legislation is a poison pill.

It is possible that advocates of reform simply acquiesce to this law for the sake of political expediency and their greater economic agenda at the 12th Congress. But it is clearly a setback to anti-corruption efforts, government accountability, and the burgeoning media sector.

If the law is passed, it would be implemented on a trial basis in 2016, with the entire consolidation process to be completed by 2020, ahead of the 13th Party Congress.

Zachary Abuza is a professor at the National War College where he focuses on Southeast Asian politics and security issues.

This article was originally published by the BBC Vietnamese Service as “Luс║нt B├бo ch├н VN l├а ‘v┼й kh├н phe bс║гo thс╗з’?“

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss