Of all the infrastructure projects established by President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) during his first term, the Makassar New Port in South Sulawesi is his crowning achievement. Built at a cost of over Rp89 trillion (A$8.9 billion), the port is one of the most expensive infrastructure projects in Eastern Indonesia. Construction first began in 2015, and is scheduled for completion by 2025.

In contrast, my hometown in the Nagekeo district of Flores, East Nusa Tenggara (NTT), has been waiting since 2016 for the Lambo dam to be built. The dam is needed to improve the water supply for household consumption and to irrigate 5,000 hectares of rice fields. Members of local adat or indigenous communities have resisted the construction of this dam, and refuse to be relocated from customary territories on which their ancestors’ graves are located. With this problem unresolved, the Rp1–1.5 trillion (A$100–150 million) project is long overdue and will not be completed by the end of the 2019 national elections.

Eastern Indonesia is one of the poorest regions of Southeast Asia, consisting of 13 official provinces including Bali, Lombok, Sumbawa, Flores, Timor, Sulawesi, Maluku, and Papua. Many of these provinces are categorised as “economically poor”. In 2018, Eastern Indonesia was home to only 15.6% of Indonesia’s total population, while the Eastern Indonesian provinces’ contribution to Indonesia’s national economic growth amounted to 20% of the national GDP. Yet the region remains afflicted by serious poverty: around 39,000 or 52% of Indonesia’s underprivileged villages, for instance, are located in Eastern Indonesia.

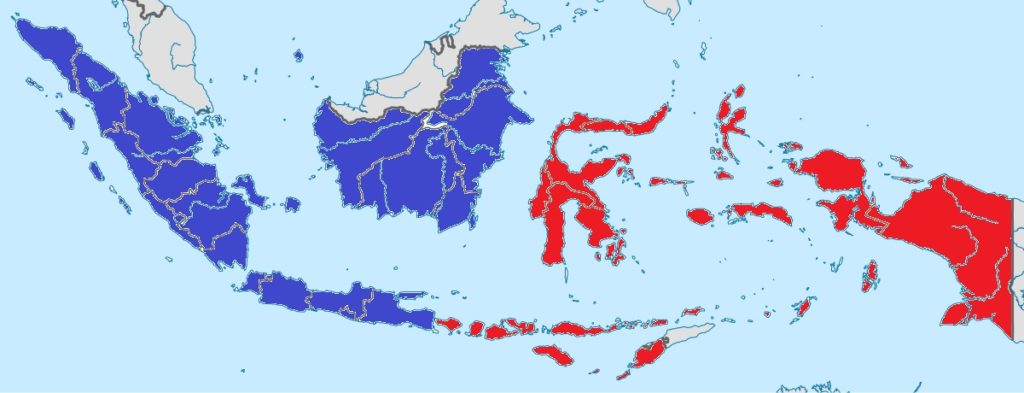

Eastern Indonesia as defined by the Indonesian government: Bali, Sulawesi, Nusa Tenggara, Maluku and Papua (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

During his 2014 election campaign, Jokowi promised to develop infrastructure projects in Eastern Indonesia. His rationale was that infrastructure development projects in Eastern Indonesia could boost national economic competitiveness, facilitate local economies, reduce regional disparities, increase connectivity between regions, and enhance the social and political unity of the nation. Eastern Indonesians supported this platform. In 2014, Jokowi won 60% of the vote across the 13 provinces in Eastern Indonesia, with huge margins in East Nusa Tenggara (NTT) (65.92%), West Papua (67.63%), Bali (71.42%) South Sulawesi (71.43%), and West Sulawesi (73.37%). From the very beginning, Jokowi has promoted his claimed philosophy of developing Indonesia from the periphery by making infrastructure, particularly in poorer areas of Eastern Indonesia, the focus of his presidency.

Has Jokowi lived up to his promise? And will the infrastructure projects that have been developed to date encourage Eastern Indonesians to vote for him again? The answer might depend on where you live in Eastern Indonesia. The contrast between Makassar and Nagekeo’s stories encapsulates the challenge of ensuring more even development within Eastern Indonesia. Jokowi’s policies have generally promoted economic growth in the province of South Sulawesi, especially the “boom town” of its capital city Makassar, while other regions remain deprived of similar attention. There is still significant economic disparity within Eastern Indonesia, which needs to be addressed in the next term of government no matter who is president.

Sulawesi-centred

Most of the designated “nationally strategic” development projects in Eastern Indonesia are concentrated in South Sulawesi province, and its capital city of Makassar. Jokowi has allocated 27 such projects for Sulawesi. (By comparison, just 13 such projects have been earmarked for the provinces of Papua and Maluku.) The establishment of Makassar New Port as the biggest port in Eastern Indonesia, as well the construction of 3 large dams and railways connecting the port towns of Makassar and Parepare, have strengthened Makassar’s position as the hub of the region. While there are seaports located in Papua and Maluku, they mainly circulate commodities (such as fish, livestock, logs, candlenuts, corns, cloves, and cashews) within Eastern Indonesia towards ports in South Sulawesi, to be then re-exported elsewhere.

South Sulawesi has enjoyed one of the highest rates of economic growth in Indonesia in the past five years: at more than 7.07%, it’s the second highest in Eastern Indonesia after North Maluku (7.92%), and is much higher than the national rate that hovers between 4.7% and 5.27%. During the period between 2010 and 2012, booms for export crops like cocoa and coffee helped South Sulawesi experience growth rates above 8%. According to 2018 data, South Sulawesi province contributed 2.43% (Rp62.3 trillion or A$6.24 billion) of Indonesia’s total national exports, the second highest rate in Eastern Indonesia after Central Sulawesi province (2.84%).

Based on these figures, Jokowi and his administration might think that injecting a huge amount of funds and projects in Makassar will boost the development of other parts of Eastern Indonesia such as Nusa Tenggara, Maluku, and Papua. However, this development approach has only resulted in continuing the economic disparity gap between Sulawesi—in particular Makassar—and other regions in Eastern Indonesia (excluding Bali, whose poverty rate of 3.91% is the lowest in Eastern Indonesia, and is the result of tourism development initiated by previous government administrations).

Under-development in Eastern Indonesia is not a new problem. For instance, in 2010, poverty rates in some provinces in Eastern Indonesia ranged from 20% to 30%—in East Nusa Tenggara (23.03%), Maluku (27.74%), West Papua (34.88%), and Papua (36.80%). The Human Development Index (HDI) scores were also low in East Nusa Tenggara (59.21), Maluku (64.27), Papua (54.45) and West Papua (59.60). In 2011, economic growth in these provinces was low when compared to South Sulawesi, as seen in Papua (-4.28%), West Papua (3.64%), NTT (5.67%) and Maluku (5.67%). In contrast, in 2010, South Sulawesi had a poverty rate of 11.60%, a HDI of 66, and economic growth of 8.19%. In 2010, Makassar city itself had a much better performance in terms of poverty rate (5.86%), HDI (77.63), and economic growth (9.83%).

Over the course of the last decade, including during Jokowi’s administration, the poverty rates in all provinces in Eastern Indonesia have reduced. But the inequality between Sulawesi and non-Sulawesi areas persists. In September 2018, three provinces in Eastern Indonesia still reported poverty rates greater than 20%: East Nusa Tenggara (21.03%), West Papua (22.6%) and Papua (27.43%). The poverty rate in Maluku was also quite high at 17.85%. When you look at the islands rather than provinces, the poverty rate in Sulawesi is much lower (10.37%) than those of Bali/Nusa Tenggara (13.84%) and Maluku/Papua (20.94%).

In contrast, the poverty rate in South Sulawesi at 8.87% was lower than the national level of 9.66%. More precisely, in 2018, Kota Makassar even had much better performance in terms of poverty rate (4.59%) compared to other regions in Eastern Indonesia. Kota Makassar’s economic growth in 2018 was one of the highest in Indonesia with 7.9%. In 2017, Kota Makassar HDI was much higher (81.13) compared to other provinces in Eastern Indonesia such as East Nusa Tenggara (63.17), West Nusa Tenggara (66.58), Papua (59.09%) and West Papua (62.99).

Aerial view of Makassar, South Sulawesi (Photo: thisisinbalitimur on Flickr, Creative Commons

Why prioritise Sulawesi?

A few factors explain the government’s apparent prioritisation of investment in Sulawesi. First is the political influence of Makassar leaders in Jakarta. Vice President Jusuf Kalla, who was born in South Sulawesi and studied at the Hasanuddin University in Makassar, has the influence to push the central government to prioritise Sulawesi interests. Other provinces in Eastern Indonesia do not have the influential political networks in Jakarta that South Sulawesi has. Some politicians have appealed to the sense of being politically marginalised: when giving a public talk in Flores in February 2019, Julie Sutrisno Laiskodat, the wife of the East Nusa Tenggara governor Viktor Bungtilu Laiskodat, announced her plan to run as a national member of parliament in the 2019 general election to represent the election area (daerah pemilihan) of Flores, based on her previous experiences dealing with politicians in Jakarta. She told voters that she had previously tried to secure funding from politicians and national parliament members in Jakarta for the construction of 700-1,000 wells in East Nusa Tenggara, only to be told: “how much will you pay us for one well?” Based on this experience, Laiskodat said she intends to compete in the 2019 general election to influence national policies on behalf of East Nusa Tenggara herself without resorting to paying off politicians in Jakarta.

In general, Eastern Indonesians do not have enough reliable representatives as ministers in the national cabinet, including within Jokowi’s administration. For instance, both Papua and West Papua provinces are represented by Yohana Susana Yembise, whose position as Minister of Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection in President Jokowi’s Working Cabinet means she holds little sway over infrastructure policies. Meanwhile there are no ministers from NTT (especially after the reshuffle in 2016), NTB, and Maluku in Jokowi’s cabinet. Representation matters. In criticising Prabowo’s lack of support for women in positions of power, Jokowi has named numerous women occupying ministerial positions in his own administration. However, he could be criticised for not giving due representation to Eastern Indonesia’s leaders.

Second, Jokowi may be prioritising infrastructure development in Sulawesi because in 2019 he no longer has Jusuf Kalla as his vice-presidential candidate to help secure votes there. In the 2014 presidential election, Sulawesi was home to over 44% of the total number of voters in Eastern Indonesia, with 20% of them coming from South Sulawesi alone. In 2014, South Sulawesi contributed a third of all votes won by Jokowi across the 13 provinces of Eastern Indonesia. Favouring Sulawesi might be one of the smartest political investments for Jokowi given the upcoming 2019 presidential election, especially since the region is home to the Muslim voters whose votes Jokowi is trying to secure.

Jusuf Kalla visiting Bili-Bili dam in Parang Loe, South Sulawesi (Photo: Vice President’s office on Instagram)

What is to be done?

Politicians and the mainstream media in Jakarta have hailed Jokowi’s infrastructure development projects in Eastern Indonesia as a great success. Jokowi has in many ways kept his promise to deliver roads, seaports, bridges and dams, electricity power plants and improvements to internet infrastructure in Eastern Indonesia. As a result, Viktor Bungtilu Laiskodat, the governor of East Nusa Tenggara (NTT), has said that “without [even] campaigning, Jokowi will easily win in NTT.”

Indeed, in less developed parts of Eastern Indonesia, small projects are having a valuable impact. In Flores, the establishment of roads to villages has enabled local villagers to access city markets where they can buy and sell their agricultural produce. The construction of embung (small dams in the savannah to store water during rainy season) in Flores, especially in Ngada and Nagekeo, has also improved the ability of farmers to water their crops and feed their livestock. The government has also allocated village funds (dana desa), which villages are using for building roads, opening farming land and providing clean water. As all the projects financed by village funds should employ local labour, the projects have helped to provide job opportunities for local people.

But if we want to close the gap between Eastern Indonesia and the more developed islands, we need to begin with a better understanding of the inefficiencies and disparities that currently shape Jokowi’s infrastructure development projects. The Indonesian government also needs to begin developing Eastern Indonesia from the village level, while ensuring the capital cities of each district have the opportunity to become “boom towns” by extending the same developments we see in Makassar to Maumere, Kupang, Jayapura, Kota Ambon, and so on.

Who’ll pay for Indonesia’s national health insurance?

Politicians need to make some hard decisions to make the system financially sustainable.

There are multiple and varied reasons which determine how Eastern Indonesians will vote in April, which include issues of religion, the personalities of candidates, the credibility of opposition candidates, and party machinery on the ground. Politicians in Eastern Indonesia have begun leveraging intolerant Islamic political movements in Jakarta to reap electoral support. In his campaign in Boawae in Flores, Andreas Hugo Pareira—a senior PDIP politician who is competing for a national parliament seat based in Flores—sought to persuade his constituents to vote for Jokowi in order to secure national unity, which has lately been threatened by intolerant Islamic political movements.

So despite what is commonly stated in Jakarta, it should not be assumed that Jokowi’s infrastructure development policy is uniformly successful throughout the region, and that Eastern Indonesians will all vote for the President on the grounds of his infrastructure policies. If Jokowi is successfully re-elected for a second term, there are areas of urgent policy reconsideration for how to reduce poverty in Eastern Indonesia.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss