The recent 2022 Philippine National Elections have been one of, if not the most, polarising and puzzling one in the nation’s political history. It had reaffirmed old and embedded principles in politics while revealing some new characteristics. The most noticeable attribute of the election is the dominance and eventual victory of Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., despite his family’s tainted reputation. Many attribute his resurgence to the rise of fake news, historical revisionism, and disinformation in social media. Sophistication and saturation of said disinformation notwithstanding, psycho-political conditions have facilitated the resonance of Marcos’ electoral campaign. Disinformation regarding the Marcos narrative has resonated because it appeals to deeper political values shared by many Filipinos who also see themselves as largely ignored by the EDSA regime and maligned by its partisans.

The absence of political parties with distinct ideologies is not tantamount to either absence or weakness. Ideology itself is irreducible to party doctrine but is, rather, constituted by both key concepts and a political value system whose coherence can be analysed through political psychology. At the heart of the 2022 Philippine elections is a leader-centric political value system which is characterised by deep political reliance on leaders.

For the case of the Philippines, leader-centrism manifests itself through the following:

First, leader-centrism involves a close political and personal identification with their individual leader. Some may label this as personality politics, but it is limited to the attraction to certain attributes of an individual leader or candidate. Rather, leader-centric tendencies involve an intense identification with the leader, in which followers construe attacks on their leader as an attack on themselves. These attacks can be attributed to online comments, content, news items, academic works or anything with opposing narratives. Thus, history, morality and facts become subservient to the success and protection of their individual leader.

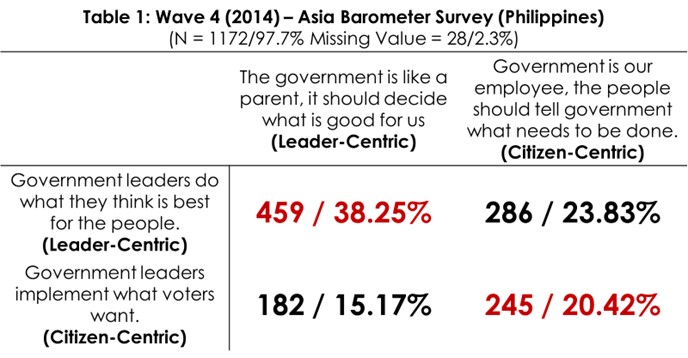

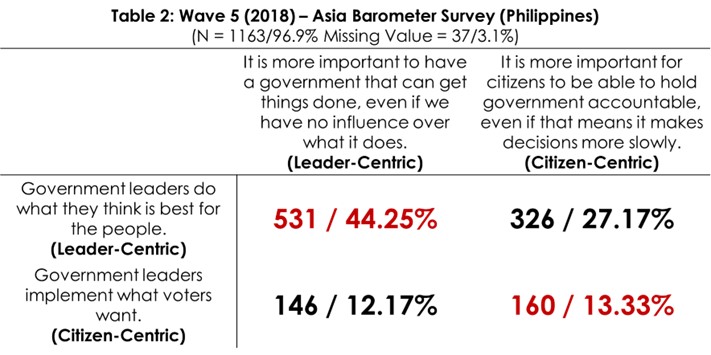

Second, leader-centrism involves the willingness to surrender public policy to leaders, along moral and patriarchal lines. A previous study on illiberalism among Southeast Asian countries shows that most Filipinos are willing to give absolute power to a leader that they consider as morally upright. Furthermore, as shown in Tables 1 and 2 below from the Asia Barometer Survey, most Filipinos have clear leader-centric tendencies in terms of both seeing leaders as a parental figure who knows what is best for the people, and as a decisive entity that can “get things done” even if ordinary citizens have neither control nor influence over the policy process. Despite the existence of hybrid tendencies, it is plausible to suggest that the Filipino political psyche is characterised by clear leader-centric tendencies at the expense of citizen-centric ones which are more suitable for the pursuit of democratisation.

Why is this the case? Where does this leader-centrism come from? Remigio Agpalo posits a “Pangulo Regime” that refers to a state under the control of the “pangulo” as the metaphorical head of the body politic. This schema connects the centralisation of state authority towards the president with the socio-political fixation on the individual leader. Agpalo also recognises that this emerges from a Filipino cultural trait of “pagdamay” or collective sharing of experiences that also identifies authoritarianism as a practical means of enforcing “pagdamay.” While Agpalo’s Pangulo Regime includes institutional aspects of government, he also connects the concept to his general observation on the Filipino’s cultural tendency to accept hierarchical structures and authoritarianism. Hence, sustaining the Pangulo Regime is a Pangulo Ideology as the collection of embedded Filipino political values and concepts that favour leader-centrism, hierarchy, and possible authoritarianism. This concept highlights the cultural and psycho-political aspects of a Pangulo Regime.

How has this “Pangulo Ideology” manifested in the recent elections? Bongbong Marcos’ campaign arguably succeeded by deploying the following key concepts more consistently aligned with a “Pangulo” ideology.

First is the notion of “Unity” or “Pagkakaisa”, the core slogan of his campaign. This embodies both the aforementioned willingness to surrender public policy to a leader as unifying entity, and intolerance towards opposition to a chosen leader. Unity also invokes the body metaphor within the Pangulo Regime discourse, which considers all followers as part of one body under the head that is Bongbong Marcos.

Second is “Pagsunod”, or compliance. A common retort uttered by his supporters is “Sumunod na lang” or “Just follow” which demonstrates the primacy of conformity as a hallmark of authoritarian tendencies in the Philippines. Though this can take the form of a broader value (i.e. compliance to the law and the government), what renders compliance a component of a “Pangulo” ideology is its application to the primacy of a chosen leader. Specifically, it becomes compliance to the will of the leader, and conformity to the groups supporting them.

Lastly is the notion of “kami laban sa kanila” or “us versus them” which embodies the tribalism that results from polarisation between competing leaders and their camps. Opposition along policy lines becomes secondary to the defence of leaders; a mark of moral politics – a matter good versus evil, of salvation and vindication – over policy oriented contention and consensus formation. Under this concept, any criticism or doubt expressed towards the leader will be considered “unpatriotic” and un-Filipino.

...grounding democracy in ambág and bayanihan can help heal the polarized political landscape in the Philippines.

Ambág and Bayanihan: The Communal Values of Philippine Populism

This moral antagonism is a product of intensified personal identification of followers with leaders as the embodiment of their political ideals and interests. These can range from a need for good governance to the outright desire for revenge. For Marcos supporters, Bongbong’s presidential campaign has been an opportunity to avenge the Marcos legacy and the loyalists who feel marginalized by the now defunct EDSA regime. Moreover, Bongbong Marcos’ silent “underdog” and “victim” approaches to sustained attacks against him and his infamous parents have amplified the fervour among his supporters to defend him. Consequently, their opponents have been pejoratively labelled as “Dilawan” or “yellows” by being associated with the Liberal Party and the EDSA People Power narrative.

The translation of leader-centric values into a “Pangulo” ideology entails the absorption of civic political life under the primacy of a leader. This can take various forms exemplified by the campaigns of both Bongbong Marcos and his main contender, Vice-President Leni Robredo. They are arguably two-sides of the same leader-centric coin. Both campaigns appealed to “Unity” albeit from different angles. The Marcos campaign deployed a generic appeal to “Unity” that allowed supporters to project their own ideals on it, subsequently disappearing into an amorphous whole. The Robredo campaign in turn deployed sectorial support through the slogan “For Leni” (ex. Teachers for Leni, Lawyers for Leni, Farmers for Leni, etc.). Both campaigns have also been marked by rabid tribalism and calls for compliance. In the Robredo campaign, this has taken the form of aggressively forwarding a liberal and anti-Marcos interpretation of Martial Law, which in turn have been met by an equally persistent defence of the Marcos legacy. Consequently, the debates on Martial Law and the Marcos legacy have led to deepening polarisation and aggression between these two camps.

A core difference with Leni’s campaign is her focus on citizen empowerment through volunteerism. For example, her volunteer-driven pandemic response has been interpreted as “upstaging” Duterte’s government or leadership, consequently offending the ideal of hierarchical structure of a “Pangulo Ideology.” The “Robredo People’s Campaign” may have attracted and activated many of the educated and progressive sectors of society but not the majority of voters still seeped in the culture of leader-centrism. It is also worth noting that Bongbong Marcos is following Rodrigo Duterte’s popular administration which affirmed and strengthened the Filipino’s leader centrism. By allying with Duterte’s daughter, Sara Duterte-Carpio, he appealed and absorbed large parts of Duterte’s pro-authoritarian base.

These are only preliminary observations and insights, but they are necessary in understanding the resonance of disinformation, the persistence of autocratic and illiberal tendencies, and the subsequent decline of democratisation in the Philippines. Even traditional political methods of propaganda and patronage can only be effective under certain cultural and psycho-political conditions. Overall, the current tension between democratisation and the Pangulo Ideology must be resolved through fair and thorough re-examination and negotiation. Only then will a more vibrant Filipino democracy emerge.

* Data analysed in this article were collected by the Asian Barometer Project (Waves 4 and 5), which was co-directed by Professors Fu Hu and Yun-han Chu and received major funding support from Taiwan’s Ministry of Education, Academia Sinica and National Taiwan University. The Asian Barometer Project Office (www.asianbarometer.org) is solely responsible for the data distribution. The author appreciates the assistance in providing data by the institutes and individuals aforementioned. The views expressed herein are the author’s own and this paper is not part of the project itself.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss