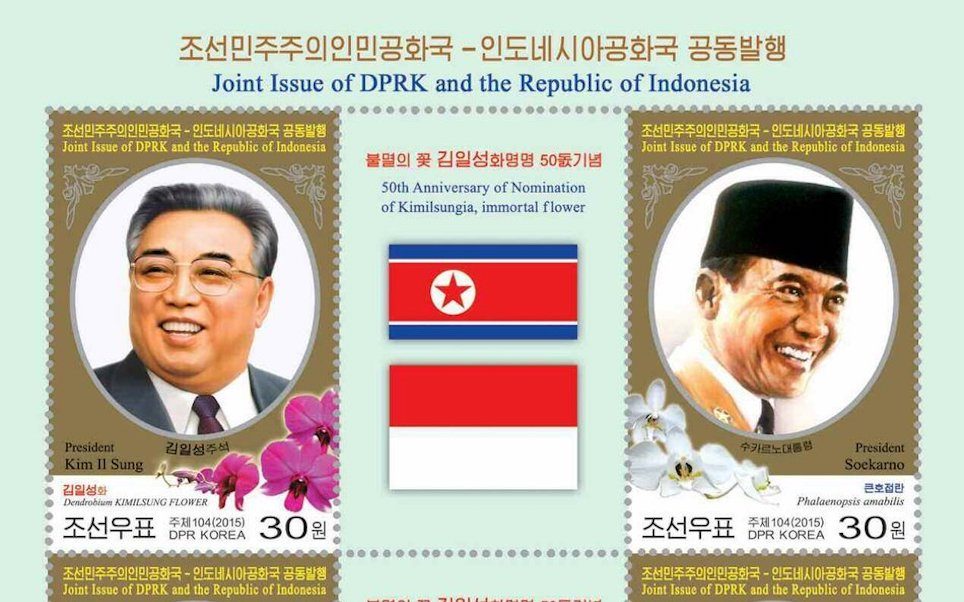

On 15 April 1965, Indonesia’s president Sukarno took North Korean Supreme Leader Kim Il-sung to the Bogor Botanical Gardens. Kim was presented with an orchard flower in his namesake: Kimilsungia.

While the visit resulted in little of substance, it remains fondly remembered in North Korea and Indonesia. In North Korea, the orchard has great symbolic value, as it was presented at a time when Pyongyang had been aggressively pushing forward a campaign of recognition and legitimacy throughout much of Asia and Africa. Kim Il-sung’s birth anniversary is celebrated with a Kimilsungia festival, where foreign dignitaries are often expected to present their own bouquet of flowers at the annual exhibition.

While having less symbolic value in Indonesia, this historical episode is still seen with elements of intrigue and, to some (especially the most ardent Sukarnoists), as a moment of pride. Kim’s 1965 visit symbolises a relatively romanticised period of Indonesian foreign policy, when Sukarno was perceived to have succeeded in manipulating great power competition to achieve a major foreign policy objective: the incorporation of West Papua into Indonesia.

Members of the Sukarno family and their supporters still maintain favourable views of North Korea. When Megawati Sukarnoputri, Sukarno’s daughter, became president, she paid a visit to Pyongyang, being the first (and thus far only) Indonesian president to visit North Korea.

Megawati’s sister Rachmawati—a lucky recipient of an honorary doctorate from Kim Il-sung University—even awarded Kim Jong-un with the “Star of Sukarno” prize “for his fight against neo-colonialist imperialism.” She also wrote a book detailing the meeting between her father and Kim, where she described the two men as “great revolutionaries.”

While Indonesia today maintains a far more comprehensive relationship with South Korea, it still maintains cordial relations with the North, even continuing to be one of the few countries in the world with an embassy in Pyongyang (though it has temporarily closed because of the COVID-19 pandemic).

In many ways, the story of Indonesia’s diplomatic relationship with North Korea remains very much a Cold War era relationship, with the Sukarno–Kim visit functioning as a symbolic remembrance of Indonesia’s non-aligned credentials (even though, ironically, this period saw deepening alignment with China). My ongoing research, which has involved archival research in Indonesia, Australia, and the United States, attempts to unpack the under-examined diplomatic history of Indonesia–North Korea relations. While ties between the two states are mostly stable and dormant, reflecting on their history offers a glimpse into the perennial struggle that successive governments—from Suharto’s new order to the President Joko Widodo’s government—have had in demonstrating Indonesia’s non-aligned credentials.

How Pyongyang wooed Sukarno

The history of relations between Indonesia and North Korea is relatively obscure. A review of Indonesia’s national archives offers little insight into the relationship. Snippets of the relationship are, however, observable from publicly available sources.

While Indonesia and North Korea established diplomatic relations in 1964, political interactions can be further traced back to the 1950s. Amid the Korean War came the question of whether Indonesia should move to recognise and support either the North or South Koreans. The Korean War was interpreted by the Indonesian government as the first major Cold War conflict. Indonesia, then newly independent, had avoided overtly taking sides in the war, as a way to assert a new postcolonial independent identity and avoid getting entangled in great power rivalry.

But a shift in Indonesia’s approach to Korea did start to develop in the mid-1950s, amid growing frustrations at the United States for its reluctance to support Indonesia’s claims on West Irian, which at that stage had still been controlled by the Dutch. This led Indonesian leaders, most notably Sukarno, to seek support for Indonesia’s claims more assertively, including through overtures in the communist world.

Chinese elites have looked to Singapore as a model throughout much of the reform era, but have failed to understand what made the city-state tick.

How Deng and his heirs misunderstood Singapore

While there was initially little interest in Jakarta to forge ties with Pyongyang, the Indonesian Communist Party (or the PKI) began lobbying for Pyongyang’s support, culminating in a joint communique calling for West Irian’s transfer to Indonesia. Not long after, there were official interests in forging a relationship. Trade missions between Jakarta and Pyongyang followed. In November 1958, the Indonesian Ambassador to China became the first Indonesian diplomatic official to visit Pyongyang, opening the “Korean–Indonesian Friendship Society”. By June 1961, North Korea and Indonesia had established trade and consular relations. Eventually, North Korea would achieve the ultimate prize when it beat South Korea to securing formal diplomatic relations with Indonesia in 1964.

Pyongyang’s success can largely be attributed to Indonesia’s increasingly leftist turn from the late 1950s, which was triggered by Sukarno’s turn to authoritarianism. After years of experimenting with parliamentary democracy, Sukarno instituted a form of autocratic rule in 1959, which he referred to as “Guided Democracy.” His centralisation of power had implications on foreign policy, as it came to reflect the president’s increasingly hostile worldview. In a series of speeches starting with one before the UN General Assembly in 1960, Sukarno blamed imperialism and colonialism for the world’s injustices.

While Sukarno was not a communist, his government admired the independent stance of the North Korean leadership. According to a 1962 US diplomatic cable, “The government of Indonesia considers that the North Korean and North Vietnamese reign control over their governments as there are ‘no foreign troops there,’ whereas this is not the case in South Korea and South Vietnam.” Furthermore, in pursuing his objective of achieving berdikari, or self-sufficiency, Sukarno had seen in North Korea a model of a successful self-sufficient economy.

Moreover, while Sukarno had mulled over the prospects of forging ties with South Korea, he likely remained cautious about its deeply anti-communist fervour. President Syngman Rhee, while already deposed by the time Sukarno established ties with the North, had drummed up support for an internal rebellion in Indonesia in the 1950s, which Seoul had interpreted as an anti-communist revolution.

The eventual formation of ties with the DPRK in 1964 paved the way for two symbolic state visits, with Sukarno visiting Pyongyang in November 1964 and Kim visiting Jakarta in April 1965. Later, in his Independence Day speech on 17 August 1965, Sukarno provided the first formal recognition of the strategic convergence between Indonesia and North Korea by declaring the “Djakarta–Peking–Pyongyang–Hanoi–Phnom Penh axis” as a force to combat the forces of imperialism.

Despite the declaration of that axis, relations with North Korea did not develop beyond existing structures. The importance of North Korea to Indonesia’s foreign policy had thus centred on the value of Pyongyang’s support for Sukarno’s status-seeking pursuits among postcolonial states. The axis would be, however, very short-lived.

Why Suharto stuck with Pyongyang

The positive trajectory of Indonesia–North Korea relations, as symbolised by Sukarno’s “axis”, stumbled following a failed coup attempt on 30 September 1965, which was blamed on the PKI. Mass killings soon followed, along with the liquidation of the PKI and the eventual removal of Sukarno from power. The anti-communist general Suharto assumed the presidency in 1967, declaring a “New Order”.

Indonesia’s foreign policy moved away from Sukarno’s anti-imperialist crusades to focus on economic development and regional security, leading to closer alignment with the United States. Meanwhile, Indonesia’s relations with several communist countries deteriorated. Suharto froze relations with China. It also closed its embassy in Cuba. But the embassy in Pyongyang remained open.

Kim’s government blamed the downfall of the Sukarno government on the jealousy of the “right reactionary forces” whose actions were orchestrated by the United States. The Indonesian Ambassador to North Korea, Ahem Erningpradja, became a pariah. Not only was his movement restricted, but he was no longer invited to events where ambassadors of friendly countries are usually invited.

In Indonesia, many argued that the relationship with North Korea should be severed, especially since the North Korean embassy in Jakarta posed security risks. In 1969, North Korean diplomats, for example, were recorded trying to kidnap South Korean businesspeople in Jakarta. There were also attempts by North Korean diplomats and intelligence officials to gather information about Western diplomatic installations, which raised concerns that they could be targets of terrorist attacks.

However, the New Order regime chose to keep diplomatic channels open. It is likely that ties were maintained to allow the New Order regime to assert Indonesia’s non-aligned credentials, especially since they had also sought to establish ties with South Korea. While Suharto may saw great value in deepening economic and security engagement with the West, there was recognition that the principle of non-alignment had remained deeply ingrained in Indonesia’s foreign policy culture. In particular, foreign minister Adam Malik was an ardent defender of non-alignment and had been cautious not to allow Indonesian foreign policy to project an overtly pro-American stance.

While ties with North Korea never truly returned to their Sukarno-era state, the relationship did begin to warm in the 1970s. Malik attempted to act as an interlocutor between the North and South Koreans, as well as the Americans, by pushing for compromises on issues preventing peaceful unification.

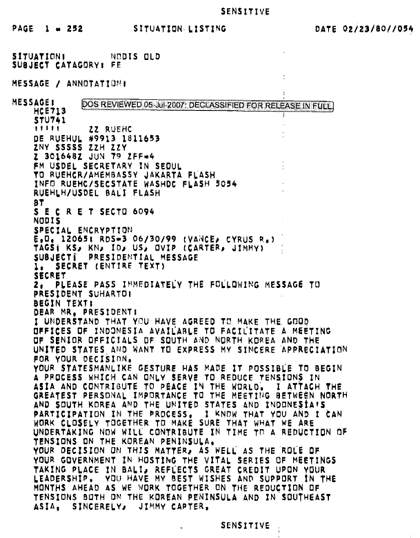

While attempts to mediate were largely unsuccessful, Indonesia’s balanced ties with the South and North Koreans did eventually culminate in a request by President Jimmy Carter, in 1979, for Indonesia to facilitate a tripartite dialogue with the US, South Korea, and North Korea to ease tensions on the Peninsula. These talks, however, never commenced, as the North Koreans showed a tepid response to the proposal for talks. Any prospect of mediation under Carter eventually collapsed when South Korean President Park Chung-hee was assassinated in October 1979. The following year, Carter was defeated by Ronald Reagan.

A 1979 cable from Jimmy Carter to Suharto thanking him for accepting the offer to house the US–DPRK–ROK dialogues.

A relationship stuck in Cold War imaginations

Despite failed attempts at mediation, ties with North Korea did serve a symbolic purpose for the New Order, just as it did for Sukarno during Guided Democracy. The case of Indonesia–North Korea ties provide lessons into one shared driver of Indonesian foreign policy under Sukarno and Suharto, which was to maintain or enhance Indonesia’s non-aligned status. Sukarno’s decision to establish, and Suharto’s decision to maintain, ties were aimed at enhancing, and later maintaining, Indonesia’s status among non-aligned states. While Sukarno sought supporters for his adventurist crusades against anti-imperialist forces, Suharto had simply wanted others to recognise that Indonesia had remained non-aligned. North Korea, a distant communist land at the centre of a security flashpoint, had been an ideal partner for Indonesia to fulfill this role.

It can be argued that Indonesia’s relationship with North Korea has remained stuck in this framework, as North Korea’s appearance in contemporary Indonesian discourse surrounds either attempts to secure a mediating role on the Korean Peninsula, or occasional expressions of pride rooted in romantic memories of foreign policy during Guided Democracy. Almost two decades after she completed her presidency, Megawati Sukarnoputri is still on a mission to bring peace to the Peninsula, preaching Pancasila and other teachings from her father at think tank forums in Seoul and in meetings with North Korean officials. Some observers even call on the government to champion Megawati as a mediator on the Peninsula today, as Kim Jong-un will have to “listen to her”, since she was a friend of his father’s and Sukarno was a friend of his grandfather’s.

As Indonesian foreign policy makers reflect on Indonesia’s role in the world as a larger, more confident nation, some are choosing to look back at any semblances of past glory for inspiration. On the Korean Peninsula, no other historical episode has a much stronger appeal than the friendship between Sukarno and Kim Il-sung. While Indonesia today maintains a highly comprehensive relationship with South Korea, Indonesia’s relationship with North Korea is one that is not only moulded by the Cold War but one that remains stuck within it.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss