When I was 10, a teacher told my class to draw a picture about Thai identity. Something that is just unique to Thai culture, tradition, and our land.

I remember it was tough. “Thai costume” seemed obvious. But my 10-year-old self already knew that our neighbouring countries also shared similar costume. At that time, I also did not appreciate Thai foods enough. So, I decided to draw a banana tree, thinking that it was so Thai.

As I was growing up, I did not think much about Thai identity or Thai-ness. But I remember knowing that Buddhism and the monarchy are highly respected. They were perceived as the driving force, the soul of the country, the reason we have survived as a nation. If you criticised them, you would be burnt in damnation, or be socially excluded, sanctioned. Or worst, face a criminal legal charge with an infamous lèse-majesté law. Back then, I had nothing against them because I was a “good” kid. To be precise, I was a relatively obedient kid who listened to adults or those in power, my parents, my aunts, teachers, and of course, the mainstream media.

In my 20s, I learned, not from the mainstream media, that during the Cold War, the fear that the communist spectres would destroy the monarchy and Buddhism led to many inhumane killings. On Oct 6, 1976, student protestors were slaughtered on the campus ground at Thammasart University, for “insulting the monarchy” and “trampling the soul of the nation”. Bodies were burnt on street. Hung on trees and beaten with a chair. In broad daylight. In front of the Emerald Buddha Temple and the Grand Palace.

Yes, I am not over that chapter of history. And how can anyone move on when Cold War’s legacies are still there, scattered all over South-East Asia?

Did I go back too far? [But does time mean anything if no one is held accountable?]

How about the Red Shirt crackdown in April-May, 2010? Streets of Bangkok soaked with blood and bodies of “bad people” who “burnt the nation” and “wanted to overthrow the monarchy”. Later, everything is swept under the rug sugar-coated with the Thai smiles. That rug was guarded with guns and law.

Some say that we should forgive and forget like good Thai-Buddhists would do. But before we even think about forget and forgive, I wonder, why good Thai-Buddhists chose and accepted barbaric killings at the first place? Since when did massacres and oppression become a path to the “righteousness”, as if there is no other way? Why do good Thai-Buddhists have such a low tolerance for different ideologies? I thought tolerance and compassion are adjacent to the heart of Thai-Buddhism. Am I wrong?

At some points, it seems like being Thai means I have to overlook the barbaric killings and the state impunity as if it is a way of life. Of course, like many Thais, I cannot forgive and forget. Let alone moving on. I cannot unlearn those traumatic facts. I cannot unsee those photographs. Every time someone said that Thai people are nice, I saw the beaten body hung from the tamarind tree. How can I forgive and forget, as I roam Bangkok streets, knowing that people were slaughtered here? When no one was held accountable for any of these cruel acts.

That official narrative of Thai-ness: I can no longer identify myself with it. But I have to admit that its toxic fruits are real and there. Since I grew up there, that toxin is a part of me too. Haunting me, deeply rooted in me, shaping the way I think, feel and behave, somehow. Even if I cannot embrace it. Even if I cannot shed it the way snakes shed their skin.

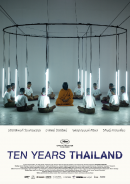

What bleak stories can be told about what Thailand will be like in a decade, when Thais have already lived under nearly five years of military rule? The film Ten Years Thailand grapples with that very question.

Film Review: Ten Years Thailand

Because national identity is not something one can erase, no matter how disappointed or betrayed one feels.

So, I have to convince myself that the official narrative is not all Thai-ness is about. Deep down, underneath my rage and disappointment, I know that Thai identity means something to me. I know it means something to me when I experience racism outside Thailand. I know it means something to me because I miss Thailand, not just my family and friends. And I miss Thai foods so bad. Sometimes when I have not had Thai foods in a while, my body feels off, as if it doesn’t know how to function properly.

******

For me, Thai identity is not just a geographical body of land and borders (nor cuisine). As I was struggling to redefine it, I found pieces of my homeland I can still love and embrace in Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s films. From a tale created by seemingly-ordinary people across the country in Mysterious Object at Noon to an afternoon escape by a factory worker and her illegal Burmese lover who has flaking skin in Blissfully Yours. A love story between a male soldier and a country boy featuring magical-tiger folklore in Tropical Malady. Male soldiers with the mysterious sleeping sickness supposedly caused by dead kings in Cemetery of Splendour. Lastly, a terminally-ill man, who has killed “too many communists”, visited by his deceased wife and his son who has left home and turned into a red-eyed monkey ghost in Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives. Uncle Boonmee also recalls his dream in which future authorities erase the people from the past.

These films are not only connected by illnesses and the tropical landscape. They also portray Thai lives in honest ways, signifying the people, their labour and local languages as well as everyday surroundings without romanticising their hardship nor employing a condescending tone. Unconventionally, they dig up unresolved/buried traumatic pasts, gently yet firmly expressing defiance of the official narratives.

Perhaps with the design of light, colours, framing, and ambient sounds, these films somehow were able to recreate memories, reminding me of this set of experiences and feelings of being born and raised there. These memories, mine and perhaps others’ as well, scatter all over the place. From the rain forest to the arid land. In trees/bushes/grasses. Mountains and hills. In animals roaming freely. The sounds of insects at dusk. On lonely country roads. Busy city streets. In food vendors, static and roving. Night markets.

In the ways music is played and languages are uttered. What [and how] people actually believe and hold on to. In the haunting red-eyed spectres of the past. In the interrupted/broken memories and the pains we carried, willingly or not. All these seemingly small things that weave Thai lives together.

Watching his films felt as if I was having an honest conversation with someone, sitting among the ruins, preparing for a coming storm. No more lies this time.

Somehow, this is warm and comforting, a moment of peace and consolation I can grab when the wave of traumas and ugly truth have crashed. And among all of these, the true meaning lies in the people who have struggled and fought to be alive and freed in that constrained geographical body. The fight has gained momentum in the last few years with the call I had not dared to dream of, they demand the monarchy to be reformed.

Today, if I were to draw something about Thai-ness. It wouldn’t be just one item. I would need a big canvas. On it I would paint a picture of a red-eyed spectre with a monitor ankle eating Pad-kra-pao in a night market somewhere, with rain forest and banana trees in the background. While the people are staring at a gigantic monument of a king, hoping their gaze will turn it into dust.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss