Much has been written of late on the growing relationship between Indonesia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), particularly its economic aspects. Over the past five years, the UAE has emerged as the largest Gulf-state investor in Indonesia, with bilateral trade projected to grow from the US$4 billion in 2021 to US$10 billion by 2030. Some US$44.6 billion in future Emirati investment has been promised, including joint development of major infrastructure, energy and IT projects.

Less attention has been paid to the burgeoning religious relations between the two nations, especially a professed shared commitment to combatting radicalisation, promoting Islamic moderation and deepening inter-faith understanding. Such commentary as has appeared in media and scholarly outlets has generally been favourable, frequently citing the complementarity of Indonesia’s rich tradition of religious tolerance with the Emirates’ well-funded international programs on peace and cross-faith dialogue.

Little critical scrutiny has been given to the details of religious relations between Indonesia and the UAE. Behind the carefully crafted statements and stage-managed events lie a tangle of domestic political and strategic interests, not all of which are shared, and nor are they necessarily likely to result in greater religious moderation in either country, let alone globally.

Here I argue that Indonesia–Emirates religious diplomacy has multiple drivers, not all of which accord with liberal notions of moderation. Moderation is commonly defined as the avoidance of extremes and display of self-restraint and reasonableness. A key difficulty here is that this is a relational definition, in that moderation is defined vis-à-vis behaviour or views that are deemed excessive. Deciding what is excessive or unreasonable is often highly subjective. Is the propagation of puritanical religious views extreme or pious, for example? Are calls for major changes to a political system dangerously excessive or legitimate comment?

Certain aspects of the moderation agenda put forward by Indonesia and the UAE do enjoin religious openness and exchange, while contesting faith-based militancy. But other aspects point to fundamentally immoderate intentions, particularly related to the suppression of domestic political dissent. Indeed, one aim of the diplomacy of moderation is to legitimise autocratic state actions that curtail the rights of civil society groups in both countries.

A ceremony marking the naming of the Jakarta–Cikampek tollway after UAE President Mohammed bin Zayed, April 2021 (Photo: Setkab RI on Facebook)

The growth in bilateral religious diplomacy

In the increasingly warm personal relationship that has grown between Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) and UAE President Muhammad bin Zayed al-Nahyan (commonly shortened to MBZ), religion comes second only to economic matters as a feature of their public utterances and policy initiatives.

When the two leaders meet, they regularly praise their respective nations’ efforts to combat radicalism and to strengthen religious moderation. During his 2021 visit to Abu Dhabi, Jokowi said: “I see that religious moderation and diversity in the UAE are widely respected. And that is the area of cooperation we would like to explore more because we both share the closeness in the vision and character of moderate Islam that propagates tolerance.”

Friendly ties to Pyongyang have been an emblem of non-alignment for generations of Indonesian foreign policy makers.

Indonesia and North Korea: warm memories of the Cold War

Over the past three years, more than 200 Indonesian imams have been sent to UAE to take up interim roles in major mosques and to “study how Islam in UAE is fully tolerant and contributes to creating peace in society”. Indonesian politicians and Islamic scholars have also participated regularly in international religious conferences run by the Emiratis and a number of eminent Indonesian academics have been appointed to the advisory boards of UAE Islamic institutions.

Commanding the most headlines has been UAE’s “mosque diplomacy”. Recently, construction was completed on a lavish US$20 million replica of Abu Dhabi’s Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque in Surakarta, Jokowi’s home city. MBZ and Jokowi officially opened the mosque in November 2022, prior to the G20 summit in Bali, to which Jokowi had invited MBZ to be a guest of honour. The mosque has been described by local officials as a “pioneer of religious moderation” which helps “address the contemporary society’s vulnerability to fragmentation”. The UAE is also currently erecting a large mosque in Jokowi’s honour in Abu Dhabi.

At first sight, there appears to be much to applaud in these closer religious ties between Indonesia and UAE. Indonesia has not previously had strong relations with any of the Gulf states, with the exception of Saudi Arabia, and even these have often been strained due to maltreatment of Indonesian domestic workers and accusations that Saudi religious influence fuels intolerance and jihadist violence in Indonesia. The UAE’s ambitious international religious moderation program brings the prospect of raising Indonesia’s profile and clout as a source of innovative thinking on religious reform.

Jokowi meets Dubai’s ruler Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum at the Dubai Exhibition Center, November 2021 (Photo: Setkab RI on Facebook)

Indonesia’s Islamic soft power

Jokowi has always had a supremely pragmatic approach to foreign affairs, viewing diplomacy as being primarily about generating economic opportunities for Indonesia, whether it be attracting foreign capital and technology or selling Indonesian goods and services abroad.. But religion—and especially religious moderation—has been a major secondary factor in his international interactions. In fact, it has become a key form of Indonesian “soft power” that he has consistently championed during his presidency.

Over the past half century, Indonesia has enjoyed a reputation abroad as a tolerant and harmonious Muslim-majority nation. Following the 11 September 2001 attacks on New York and Washington DC, and the ensuing “Global War on Terror”, Indonesia attracted Western attention as one of the few Muslim-majority democratic nations in the world that proudly proclaimed its moderation, and was thus feted as an example from which other Muslim countries should learn.

Jokowi’s predecessor, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, Indonesia’s most diplomatically adept president, traded heavily on this moderate image and strode the world extolling his nation’s religious virtues. Major Indonesian Islamic organisations also sought to benefit by seeking funding from foreign donors for their “moderate” educational and outreach programs, including scholarships, money for schools and development of anti-radicalisation projects.

Soon after becoming president in 2014, Jokowi took up the Islamic moderation theme in a more specific way than Yudhoyono. He adopted the Islam Nusantara (Archipelagic Islam) concept formulated by Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), Indonesia’s largest Muslim organisation. The concept’s essence was that Indonesian Islam had unique and commendable characteristics because it married local culture with Islamic legal and theological traditions. NU intended the concept to challenge what it saw as a growing “Arabisation” of Indonesian Islam driven by the belief that Middle Eastern Islam was superior to, or more pure than, indigenous variants. Jokowi gave prominence to Islam Nusantara in numerous speeches abroad for several years (albeit without mentioning Arabisation) and he also instructed his foreign ministry to incorporate Islam Nusantara into its official messaging.

This had both political and diplomatic motivations. NU is Jokowi’s chief base of support among Muslim voters, a majority of whom voted for his opponent, Prabowo Subianto in the 2014 and 2019 presidential elections. Without NU’s backing, Jokowi would likely have lost both races.

A grateful Jokowi was happy to expound NU’s Islam Nusantara and raise the organisation’s profile globally. NU had long felt that it had far less international attention than it deserved, given its size and the quality of its Islamic scholarship, and therefore welcomed having its ideas presented abroad. Jokowi probably also felt that Indonesia’s religious moderation was a natural diplomatic selling point among Western leaders preoccupied with the threat of Islamic militancy.

Jokowi with former NU chair Said Agil Siradj (left) at an NU conference, West Java, February 2019 (Photo: Setkab RI on Facebook)

After several years, Jokowi shifted the focus of his moderation messaging as the limitations of Islam Nusantara became apparent. Most Indonesian Islamic organisations were cool on the concept, seeing it as too NU-centric and not representative of their own religious views and practices. Moreover, doubts arose about the applicability of Islam Nusantara to other Muslim societies.

In 2018 Jokowi signalled a change of tack by appointing Din Syamsuddin, the former chairman of Muhammadiyah, NU’s great rival, to a new position of Special Presidential Envoy for Interfaith Dialogue and Cooperation. A conference of international scholars was organised in Indonesia in the middle of that year, which endorsed “Islam Wasatiyyah” as a pivotal concept for promoting peace and tolerance. The term wasatiyyah had the advantage of already being in common international usage and acceptable to a wide range of Muslim states and movements. Thereafter, Jokowi and his officials made frequent reference to Islam Wasatiyyah, thereby allowing Indonesia to more easily align with international Islamic discourses.

The election of Yahya Cholil Staquf as NU chairman in late 2021 has seen Jokowi again show strong favour to NU as a source of religious diplomacy. Yahya, who has long been close to Jokowi and is a member of the president’s advisory council, had been diligently pursuing building international networks over several years, using various concepts, the most recent of which is called Humanitarian Islam.

NU chair Yahya Cholil Staquf (centre) receives an award from a delegation of monks from Cambodia at the R20, Bali, November 2022 (Photo: R20 Indonesia 2022 on Facebook)

The most controversial part of the Humanitarian Islam concept is its call for thorough-going reform of Islamic jurisprudence as a means of delegitimatising radical interpretations and creating more tolerant and irenic understandings. Yahya persuaded Jokowi to support a new religious dialogue initiative known as the Religious Forum 20 (R20) in the run up to the G20 summit in Bali in November 2022, of which Indonesia was the chair. Generous funding for the event was secured from Saudi Arabia’s Muslim World League.

This decision was controversial as the R20 displaced the long-established US-based Interfaith Forum 20 (IF20) which had preceded annual G20 meetings since 2014. Opinion is divided within officialdom and civil society regarding the outcome of the R20, and there is now intense competition between R20 and IF20 to organise the 2023 pre-G20 religious forum in New Delhi. Jokowi has sought to strengthen the R20’s bid by making NU the permanent organiser. If the R20 is unsuccessful, it would be a blow to Indonesia’s efforts to place itself at the centre of global religious diplomacy.

The UAE’s moderate makeover

The Emirates, like Indonesia, regards the economic aspect of the bilateral relationship as the most important, but in its case, the nexus between religious and economic issues is far more tightly interwoven than is the case for Indonesia. The UAE is pursuing a policy of economic transformation in order to create a thriving, sustainable post-fossil fuel-based economy. This not only involves diversifying UAE’s predominantly oil-based economy by attracting and developing a wide range of new industries—such as IT, clean energy technology, financial services and defence manufacturing—but also creating a cosmopolitan and multi-cultural society which is enticing for expatriates who will bring the necessary expertise to enable sweeping economic restructuring.

A ceremony inaugurating the naming of a boulevard in Abu Dhabi as President Joko Widodo Street, October 2020 (Photo: Abu Dhabi Media Office)

The UAE has pursued a “Look East” policy for the past decade, placing greater focus on Asia. Indonesia, the largest economy in Southeast Asia and with prospects of becoming one of the world’s top five economies in the next decade or two, presents an attractive option to the Emirates.

Religion is a key part of the Emirates’ makeover. MBZ, the main architect of this this process, is determined to replace the his country’s image as a traditional, rather puritanical Islamic society with one that is open, pluralistic and welcoming of different faiths and cultures. An ambitious program has been implemented over the past 15 years to achieve this, placing particular emphasis on interfaith outreach and Islamic moderation. The UAE has opened diplomatic relations with Israel as part of the 2020 Abraham Accords and is now constructing a massive multi-billion-dollar Abrahamic Family House in Abu Dhabi which will feature a Catholic church, a synagogue and a mosque—all on an opulent scale. It describes the project as a manifestation of “Common Humanity”. The Emirates is also building large Hindu and Sikh temples and has funded a succession of international interfaith conferences and initiatives.

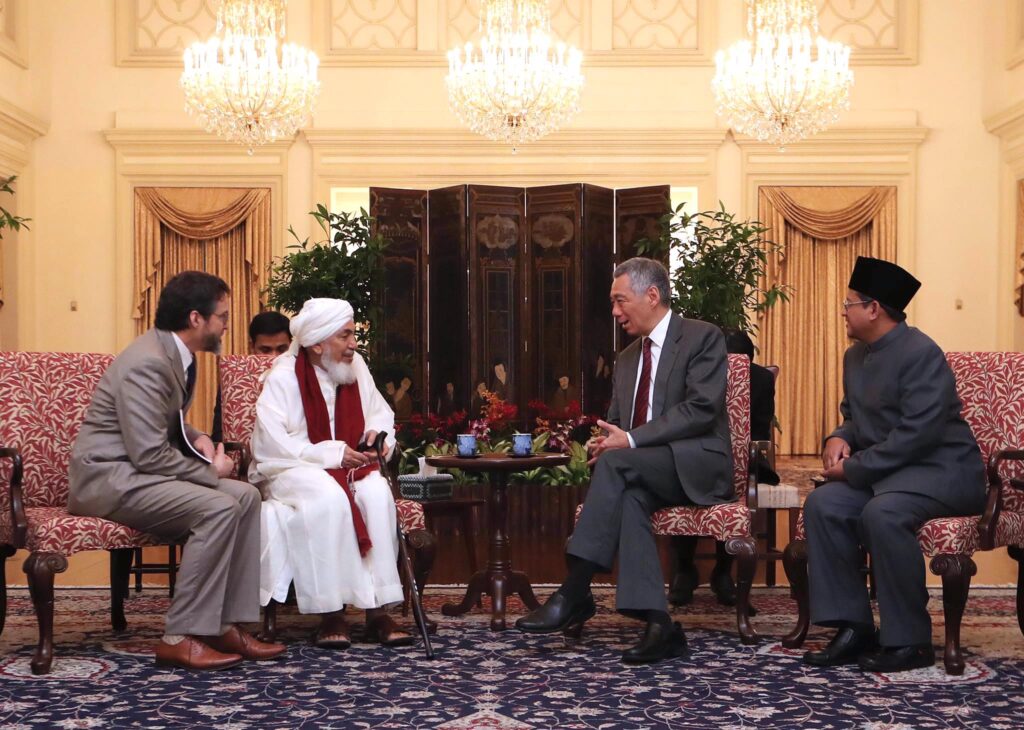

Establishing itself as a credible voice for moderation has been more challenging for the Emirates as it lacks home-grown ulema (Islamic scholars) and institutions of high standing in the Muslim world. As a result, it has had to recruit reputable ulema from abroad and form new organisations capable of raising UAE’s religious profile. Its chief recruits have been Sheikh Abdallah bin Bayyah, a Mauritanian scholar; his student Sheikh Hamza Yusuf, a prominent US-based scholar; and Sheikh al-Habib Ali al-Jifri, a Yemeni Sufi (mystical) scholar.

New institutions followed soon after. In 2013 the Forum for Promoting Peace in Muslim Societies (FPPMS) was founded, headed by bin Bayyah, with the aim of building international networks and producing Islamic scholarship supportive of moderation. Bin Bayyah has published extensively and travelled the world propounding his views on religion and peace as well as correct political behaviour for Muslims. The following year, the Muslim Council of Elders was set up, with the stated objective of “extinguishing” sectarian and jihadist “fires” in the region and promoting humanitarian values. Ali al-Jifri’s main vehicle was the Tabah Foundation, which challenges what it sees as “fundamentalist” thought using Sufi ideals. The UAE also founded Hedayah, an international body to counter violent extremism, and created a Ministry of Tolerance in 2016.

L–R: Hamza Yusuf, Abdallah Bin Bayyah, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and then Grand Mufti of Singapore Mohamed Fatris Bakaram, at the prime minister’s residence, Singapore, March 2017 (Photo: Muslim Peace Forum on Facebook)

UAE religious engagement with Indonesia is part of this effort to rebrand the Emirates; Indonesia’s reputation as a stronghold of religious tolerance makes it a useful partner. In effect, the Emirates is hoping that closer and more high-profile relations with Indonesia and other religiously diverse and tolerant nations will reflect positively upon it, helping it to appear more like its international partners.

Indonesia and the UAE also have similarities in their legal and devotional practices that make international partnerships easier. The Emirates is often incorrectly seen as sharing the strict Wahhabist doctrine of its neighbour, Saudi Arabia—but it in fact adheres to the mainstream Sunni law schools and has strong Sufi traditions, as does Indonesia. UAE religious institutions such as the Muslim Council of Elders and the Tabah Foundation directly contest Wahhabist doctrine, as also does NU in Indonesia, and they deploy the term Ahlul Sunnah wal Jamaah (“followers of the tradition of Prophet Muhammad and the community”—in effect, mainstream Sunni Islam) in seeking to exclude Wahhabists and other perceived fundamentalist groups.

Indonesian Islamic scholars with expertise in traditional jurisprudence thus have much in common with their Emirati counterparts. Several senior Indonesian Islamic scholars, such as Professor Quraish Shihab, hold advisory board positions in Emirati Islamic organisations. In 2022, FPPMS bestowed on Jokowi the Hassan bin Ali International Peace Prize for his G20 leadership and also invited Indonesia’s vice president to be a keynote speaker at their annual Peace Forum. For its part, Indonesia ensured that Abdallah bin Bayyah spoke at the R20 conference in Bali and at other interfaith events.

Less moderate than it seems?

To what degree is the Indonesian and Emirati rhetoric of tolerance and moderation genuine? At one level, both nations have a strong interest in enjoining moderation. Indonesia has grappled with a serious terrorism problem since the early 2000s, and, although attacks have been rare in recent years, much is due to successful police counter-terrorism operations rather than ebbing terrorist recruitment. The UAE’s terrorism threat is less severe but nonetheless present.

Whether the kinds of “civilisational” discourses favoured by the two governments will have any effect on extreme radicalisation is questionable, given that militant Muslims usually reject the authority of mainstream or official ulema. Undoubtedly, also, both Indonesia and the Emirates aspire in a broad sense to have harmonious, plural and tolerant societies, and are bent on inculcating these values in their communities. Their espousal of religious moderation thus has some substance.

But at another level, Indonesia and UAE are using “moderation” in an instrumental and selective way for domestic political purposes. Both the MBZ and Jokowi governments have repressed local Islamist movements, often using methods that breach civil liberties. The UAE aggressively targets Islamists, particularly the Muslim Brotherhood and its sympathisers, which it sees as one of the major sources of opposition to the monarchy. Amnesty International says there are currently at least 32 political prisoners in jail and in recent years almost 100 Muslim intellectuals and activists from the Brotherhood-linked al-Islah Islamist group have been tried and jailed under a vaguely worded but draconian counter-terrorism law. Moreover, the UAE uses state-employed ulema, such as Bin Bayyah and Hamza Yusuf, to argue for political quietism and obedience to the ruler, thus seeking to cast dissent as sinful.

A campaign poster spruiking FPI and other hardline leaders’ support for Prabowo Subianto’s presidential campaign, 2019 (Photo: Liam Gammon)

The Jokowi government has also quashed Islamist activism that it deems a political threat, albeit somewhat less harshly. It banned Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia in 2017 and the Islamic Defenders Front in 2020—movements which had tens of thousands of members—on grounds including involvement in terrorism and sedition that many observers believe to be unsubstantiated. Numerous Islamist leaders have either been charged and convicted of questionable offences or forced from public view on threat of investigation into alleged criminal behaviour. Both governments behave immoderately when it comes to suppressing opposition but use their religious diplomacy of moderation to deflect attention from their autocratic tendencies. Most of their fellow world leaders are happy to ignore or play down such excesses.

Friendly ties to Pyongyang have been an emblem of non-alignment for generations of Indonesian foreign policy makers.

Indonesia and North Korea: warm memories of the Cold War

Despite the lofty rhetoric of Indonesian and Emirati religious diplomacy, hard-headed and politically self-interested considerations drive the use of moderation and tolerance as strategic commodities. If aspects of these religious programs succeed in implanting moderate and pluralistic values in their respective societies, then there will be cause for praise. But it is also the case that moderation has also become a tool for crimping the ability of Indonesians and Emiratis to organise and express themselves freely. From this perspective, the diplomacy of religious moderation has an empty ring to it.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss