Ever since COVID-19 first emerged in Myanmar in March 2020, the worsening health crisis has been closely tied to ongoing political upheaval and violence across the country.

Healthcare workers and students who had been volunteering on the frontlines of the public health response have formed the heart of the country’s civil disobedience movement (CDM) against the junta, following the 1 February coup. Many have been attacked, killed and jailed by the Burmese armed forces (Tatmadaw), as the third wave of the pandemic has seen Delta variant cases and deaths rise over the last month.

The intersection of the country’s dual crises and a particular focus on the lived experience of those affected, was effectively captured in the theme of the 2021 ANU Myanmar Update: “Living with the Pandemic and the Coup.”

The ‘Political Update’ was delivered by Dr Morten Pedersen from the University of New South Wales, Canberra. Dr Pedersen’s presentation focused on possible explanations for the coup and offered a perspective on the likely outcome of the present political situation. While a single or exact cause of the coup may ultimately be impossible to identify, Dr Pedersen suggested that there were three broad factors which likely played a role.

Firstly, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing is approaching the age of compulsory retirement. Unlike former President Thein Sein, who was able to retire in relative security by placing trusted officers in key leadership positions, Hlaing has not established a similar safety net. Soon after the coup, the State Administration Council removed the age limit for the Senior General and his deputies.

Secondly, Pedersen highlighted several points of growing tension and disagreement between the democratically elected civilian government and the Tatmadaw which were likely to have been perceived by the military as “outside or not in line with the spirit of the 2008 Constitution.”

This included the appointment of Aung San Suu Kyi as State Counsellor and the appointment of a civilian National Security Advisor, Aung San Suu Kyi’s refusal to convene a National Defence and Security Council, the transfer of the General Affairs Department away from the military-controlled Ministry of Home Affairs, and the civilian government’s establishment of an independent inquiry into Rakhine State.

The third factor was the dismissal of military protestations about the 2020 election results. Even though objective election observers found no evidence of significant fraud that would have changed the outcome, the Tatmadaw clearly viewed the results as suspect. To what extent the National League for Democracy (NLD) government could have allayed concerns and avoided the coup is difficult to assess, but meetings between the NLD and military in the lead up to February 1 likely paved the way for the Tatmadaw’s response.

Reflections on the 2020 election continued at the Update with a panel on “Politics, the election and the pandemic.” Michael Lidaeur from Goethe University in Frankfurt and Gilles Saphy, from Election Observation and Democracy Support, presented a summary of their findings on the election. COVID-19 presented “new challenges, news stresses, risks and questions”. While there was debate as to whether the elections should have been postponed given the pandemic, those who did argue for postponement called for a 2–3-month delay at most. Lidaeur and Saphy found that the pandemic contributed to an uneven playing field to the detriment of less established parties and candidates, as anti-COVID measures placed restrictions on freedom of movement and assembly, affecting the capacity of political parties to campaign and for voters to engage in the election.

Constant Courant from the University of British Columbia continued the election discussion, presenting on the topic of the electoral performance of the military’s proxy party, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP). Outlining the connection between state capacity, credibility, patron-client networks and the election results, Courant argued that the USDP was successful in areas where the NLD had failed to distribute public goods. However, the USDP weakened its position due to its inability to capture state apparatus, providing an additional motivating factor for the post-election coup.

The final speaker on the panel was Tomas Martin, who was also presenting on behalf of anonymous scholars, on the topic of Myanmar’s prison systems. While both COVID and the coup have highlighted the harsh conditions for prisoners and detainees in Myanmar’s prison, Martin repeatedly emphasised that crises are not unusual for those incarcerated, but in fact are “the norm.” “Scarcity, misinformation, and violence are part of prison life before COVID and the coup.”

Martin’s presentation included harrowing accounts of those with firsthand experience inside the prison system, including mentions of how health orders are arbitrarily enforced or ignored at the expense of detainees. He concluded that the health response has been repeatedly undermined and hampered by the authoritarian tendencies of the coup leaders, with many missed opportunities for transparency and reform.

...with COVID-19, and a coup, predicting the course of Myanmar’s future may best be put in the hands of the astrologers.

Reflections on the 2021 Myanmar Update in troubled times

The second day of the Update was closed with a special presentation from Salai Lian Hmung Sakhon, Minister of Federal Union Affairs of the National Unity Government (NUG).

Dr Sakhon spoke about the present aims of the NUG, which include applying internal and external pressure on the coup leaders, building unity amongst themselves and supporters, and meeting the needs of ordinary people through the provision of support for those engaged in CDM.

As Minister for Federal and Union Affairs in the NUG, Dr Sakhon also expressed his focus on creating a new federal constitution, however he emphasised that the primary and present goal is to remove the military regime and Min Aung Hlaing. “Defeating Min Aung Hlaing is Day 1 job, developing is a Federal Constitution is a Day 2 job, but we should also prepare for our Day 2 job.”

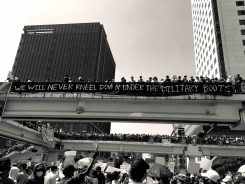

Given the present challenging circumstances in Myanmar there was limited optimism amongst many of the Update’s speakers for the immediate future in Myanmar. There were, however, some common threads of hope with regards to Myanmar’s younger generations, who have taken to the streets in protest.

Comparing his own experience as student during the 88-uprising with young people of today, Dr Sakhon expressed his optimism: “The new generation I think is ideologically much, much smarter than our generation. We demand for democracy, but we did not know how democracy functions. This generation at least enjoyed two terms of elections, two terms of government. They enjoyed freedom of expression.”

Dr Pedersen’s political update was similarly closed with his reflections on Generation Z.

“We have all seen what they are capable of. We’ve seen, and I’ve been particularly impressed by these visions that we now hear coming out of a much more inclusive, a more tolerant, a more just society. We don’t really know how widespread those sentiments are, but they are being expressed by a range of leaders and individuals who we know that, even before all this, had a major influence on that generation.”

These, amongst other comments from presenters at the Update, reflected a clear recognition of the hope, personal strength, and resilience of those who are living with the challenging circumstances facing Myanmar today. While the future is uncertain, the Update Conference will continue to be an important focal point of support for Myanmar and Myanmar scholarship when it returns in 2023.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss