Ten ways Myanmar’s military can make life very difficult for Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD.

Over the past few months, articles and op-eds by experts and others on Myanmar’s general elections have covered almost every conceivable aspect of the subject. Also, it seems a shame to dampen down the wave of euphoria that has swept around the world since the National League for Democracy’s (NLD) stunning victory on 8 November, which promises a new beginning for a country and people that have suffered for decades.

In considering where recent developments might lead, however, it is important to take a broad view and keep the election outcome in perspective. As Nicholas Farrelly wrote in The Myanmar Times on 9 November, this is just the beginning of a very long and difficult process. The harsh realities of power in Myanmar – at least as far as they have been seen until now – demand a fair degree of caution.

It might be helpful to list a few basic facts of life in Myanmar, just to set the scene.

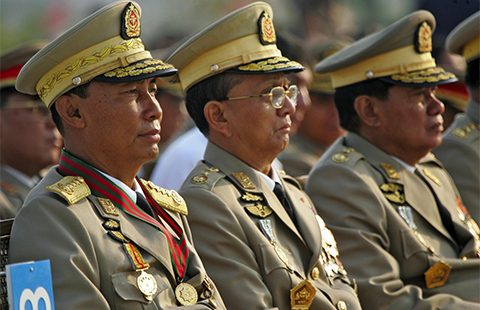

First, the armed forces (Tatmadaw) have long been and arguably remain the most powerful political institution in Myanmar. As Robert Taylor has written, ‘Only the army can end its own role in Myanmar’s politics, and that decision is dependent on its perception of the civilian political elite’s ability to manage the future’. He might have added, ‘and protect the Tatmadaw as a national institution’.

Second, it is also important to bear in mind that the elections were relatively free and fair, and produced a reasonably accurate result, only because the leaders of the armed forces permitted them to occur and did not interfere. It may not have been easy, but they could have intervened at any stage of the process and ensured that the elections were cancelled, postponed, or manipulated to give a different outcome.

Third, given their resources and control of Myanmar’s internal affairs, the generals must have known that a free and fair election would result in a decisive victory for Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD. The final statistics may have come as a bit of a surprise (before the poll some respected analysts were questioning whether the NLD could achieve a landslide), but the outcome could not have been in doubt.

Fourth, this being the case, it can be assumed that, well before the election took place, the Tatmadaw’s senior leadership, probably in consultation with the president, took a collective decision to accept the results. There is no real tradition in Myanmar of sharing political power, but they must also have faced the prospect of negotiating the future governance of the country with Aung San Suu Kyi and her party.

And, rest assured, it will be a matter of the Tatmadaw and the NLD having to strike a deal of some kind. The massive show of popular support for Aung San Suu Kyi and her party on 8 November gives them enormous moral authority and a strong bargaining position, but it does not guarantee them a free hand to shape Myanmar’s future. Under current circumstances, that can only be done in cooperation with the armed forces.

Neither the Tatmadaw’s leadership, nor Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD, would gain anything from a direct confrontation. That would only cause internal turmoil, hurt the Myanmar people and see Myanmar condemned internationally. If it got out of hand, such a clash of wills would inevitably slow down the democratic transition process. In certain circumstances, it could even halt it. That would benefit no-one.

While she has her critics, Aung San Suu Kyi enjoys strong support both inside Myanmar and outside it. Until now, however, her ability to work the levers of power has been heavily circumscribed. The NLD’s expected control of the national parliament opens up a number of intriguing possibilities, but there are still many ways in which the Tatmadaw could make life very difficult for her and the party, if it chose to do so.

Let me point out 10 of the more obvious ones.

One, the 2008 constitution could have been written with the current scenario in mind. The generals clearly anticipated the possibility that the armed forces might one day be faced with a potentially hostile parliament. So they built in various measures to protect the Tatmadaw’s position and core interests, and to guarantee its central role in national affairs. That is why the generals view the constitution as ‘the main or mother law’ of Myanmar, which they are determined to safeguard.

Two, any attempt to challenge the Tatmadaw’s status will be resisted. It has already rejected moves to reduce the guaranteed 25 per cent military representation in all national and regional assemblies. It has also opposed moves to amend the constitution so that Aung San Suu Kyi can become president. Amendments have not been ruled out entirely, but military spokesmen have said they will only occur when Myanmar’s democracy has ‘matured’. The Tatmadaw will decide when that stage has been reached.

Three, under the 2008 constitution, the Commander-in-Chief (CinC) of Defence Services has wide discretion to intervene in Myanmar’s internal affairs. With the president’s approval (and remember Thein Sein will remain in office until March 2016) he can even declare an emergency and take over the entire government. However, there is a lot the Tatmadaw can do to influence events short of such an extreme step.

Four, the constitution specifies that the portfolios of defence, home affairs and border affairs are filled by serving military officers recommended by the CinC. Also, if the Vice Commander-in-Chief is included, the CinC exercises effective control over at least five of the 11 members of the powerful National Defence and Security Council. These arrangements give the Tatmadaw effective control over Myanmar’s internal affairs.

Five, should a NLD parliament put pressure on the Tatmadaw, by trying to reduce its share of the national budget, there is bound to be pushback from the armed forces on the grounds that they have a duty to ensure the country’s unity, stability and sovereignty. In any case, under a 2011 law, the Tatmadaw is permitted to use other means to find the resources they need to meet their responsibilities. They already receive funds from a range of off-budget sources.

Six, the role of the armed forces in the national economy has been gradually declining since 2011, as the Tatmadaw has given up some of its monopolies and its two main conglomerates, the Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings Ltd and Myanmar Economic Corporation, have begun paying taxes. Should it wish to do so, however, the armed forces and their powerful ‘cronies’ could still exert pressure on the government by exercising their considerable economic power.

Seven, Aung San Suu Kyi knows that an early resolution of the country’s long-running insurgencies will be one of the NLD’s most pressing policy issues once it takes office. Yet, there is no hope of a more comprehensive ceasefire agreement – let alone a nation-wide peace settlement – without the full cooperation and support of the armed forces which, under the constitution, are guaranteed complete autonomy in all military affairs.

Eight, it is also relevant that the government and civil service are dominated by ex-military and military personnel. Out of 46 ministers at the national level, 37 are currently from the Tatmadaw, including five on active duty. Of the 14 Chief Ministers of Myanmar’s states and regions, all but one are retired military officers. These numbers will change as a result of the latest elections, but at least 170 retired senior officers stood for parliament on 8 November and some will probably secure a seat, if not official appointments.

Nine, in addition, 80 per cent of senior civil service positions in Myanmar are filled by ex-servicemen and women. Of the 33 permanent secretary positions created this year, 23 are held by former military personnel. As Renaud Egreteau has written, over decades the senior officer corps has been socialised into believing that the Tatmadaw is the sole and uncontested embodiment of the state. Even under a NLD government, many positions of authority will be under the influence of former military officers with a strong institutional loyalty to their old employer.

Last, but by no means least (and the country’s non-state armed groups aside), the Tatmadaw exercises a monopoly of the means of applying physical force in Myanmar. The CinC not only controls the powerful 350,000 strong armed forces but also the 80,000 strong Myanmar Police Force (with its 30-plus armed security battalions), militia units and other paramilitary forces, the Fire Brigades and even the Myanmar Red Cross.

Through these and various other measures, the armed forces have the means to exercise a powerful influence over Myanmar’s political, economic and social affairs, short of direct intervention. In considering the way ahead, Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD will need to make due allowance for this reality, and come to some kind of modus vivendi with the military leadership. To reject such a course of action would see everyone suffer.

Individuals on both sides of the political divide are convinced of the validity of their respective positions. Also, they can be very stubborn, and prone to saying and doing unhelpful things. There is a risk, for example, that Aung San Suu Kyi will appeal to the armed forces over the head of the CinC, counting on the apparent support in the ranks for further reform. Any challenge to the loyalty and cohesion of the Tatmadaw, however, would arouse the generals’ deepest concerns, with possibly dire consequences.

All that said, both sides have shown that they can be pragmatic when it suits them. If they accept that their best option is to work together for the good of the country, and permit each side to pursue their core interests without threatening the other, then Myanmar may be able to look forward to happier times.

Should one side insist on exercising its perceived prerogatives over the objections of the other, however, or strong personalities adopt rigid and uncompromising positions, then the outlook will be much darker.

Whatever happens, Myanmar’s future will continue to defy confident prediction.

Andrew Selth is an Adjunct Associate Professor at the Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs, the Australian National University.

This article forms part of New Mandala’s ‘Myanmar and the vote‘ series.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss