Over the last 2 years, the ABC’s news website has featured at least six stories focussing on cruelty to animals in Indonesia. The stories are accompanied by graphic images and a warning: ‘This story contains graphic images that some readers may find distressing’. The ABC has not paid equivalent attention to violence against animals in any other foreign country during this period. Indonesia seems to be the site of choice from which the ABC sources images of cruelty to animals. Furthermore, the experts and commentators encountered in this coverage are almost invariably Australians or Europeans, which gives audiences the incorrect impression that it is only Australians or Europeans who are protecting animals from cruelty in Indonesia.

Australians continue to know little and think poorly about Indonesia. This is a little puzzling, for there are many reasons to think these problems might have disappeared. For example, Australians love Bali, and for decades Australian governments have been introducing programs to make it easier for young Australians to study Indonesian language and to visit the country.

We have had ample opportunity to broaden public knowledge of Indonesia beyond beaches, terror and natural disasters, and to recognise the amazing array of civilisations and cultures that combine together under the flag of the Republic of Indonesia. Yet the Lowy Institute, which regularly polls Australians to establish their attitudes towards countries in our region, concluded this year that “Australians continue to demonstrate a lack of knowledge about, and trust in, our largest neighbour, Indonesia”.

Media representations clearly have much to do with these public attitudes. The ongoing broadcast of negative images about the country has probably dissuaded all but the most curious from wanting to know the realities of Indonesia. Australian media do not malevolently or ignorantly circulate negative images; they have moved beyond the attitudes that in the past underpinned media misrepresentations about Asia. Rather, the construction of negative impressions happens almost invisibly as a by-product of well-meaning coverage of problems with which we are legitimately concerned. The ABC’s reportage of violence towards animals illustrates how this happens.

The ABC’s journalists do not search for or create this content. It comes from advocacy groups independent of the ABC, or is sourced from Jakarta’s English language news media. Occasionally ABC journalists write as guests of advocacy groups, which invite journalists to participate in their media strategies. So, when the ABC journalist Anne Barker was hosted by the World Wildlife Federation at a nature reserve in Indonesia’s Riau province, she joined Richmond footballers who had also been brought there for the promotion (Sumatran Tigers on the Brink of Extinction, 3/12/19).

The WWF, ABC and the footballers are doing valuable work in drawing attention to animal populations at risk. But must Indonesia continually be the location from which images of cruelty are sourced? By relying on Indonesia as the source above other countries, and by circulating the associated images so liberally, the ABC is unwittingly constructing and affirming an unfair and inaccurate image of the country.

Animals Australia

In recent years, the ABC has frequently obtained Indonesia-related material from Animals Australia. This organisation provides the ABC with content sourced by its staff and investigators, and the ABC circulates it. The synergy between the two organisations is understandable. Animals Australia plays an important role in drawing attention to cases of cruelty to animals. The ABC recognises correctly that most Australians accept this issue as one that concerns the national interest.

In some stories, the relevance to Australian government policy is direct: Animals Australia has done valuable work in advocating compliance with the Exporter Supply Chain Assurance System (ESCAS), a code governing the conduct of animal export established by the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment.

Yet there are dimensions to this collaboration that we ought to question. For one thing, there are never any stories in which visual images are not central. These images encourage readers to click into the content, but they keep a triangle of re-occurring elements before the attention of ABC readers: graphic depictions of cruelty to animals, judgements such as “inhumane” that scream from the headlines and warnings, and thirdly, the fiction that Indonesia is the prime site for the occurrence of such cruelty.

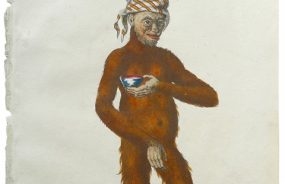

One can understand why the Animals Australia website would make use of such shocking imagery. Animals Australia is an activist group advocating for its ideological position, and the group should not be expected to give much consideration to the geographical source of its images. The images enable it to convey its messages effectively, and are important for its fundraising efforts. The first image welcoming visitors to its website is an image of a lamb with pleading gaze. The ‘Donate Now’ button sits centimetres from the lamb’s eyes. The cute images sit beside horrifying images of violence towards animals – many of them recorded by the group’s activists during visits to Indonesia. The donate button sits close to these images also.

But must the ABC cooperate so actively in the circulation of images provided by Animals Australia? The ongoing coverage is creating an unfair and untrue impression of Indonesia for Australians. This impression could be righted with recognition of two other strands of the story.

The true story behind animal cruelty

First, Indonesia is not as different from Australia as these images suggest. In fact, Indonesia has an enthusiastic and well-supported animal rights lobby.

Indonesian volunteers rally around the programs of Profauna, for example, a not-for-profit established in East Java in 1994 to protect animals from illegal trading and habitat destruction caused by logging. Animal welfare organisations and clubs gather increasing numbers of like-minded people to raise awareness and activism. Popular celebrities such as Davina Veronica and Nadya Hutagulung leverage their profiles in order to publicly advocate on behalf of animals, just as Brigitte Bardot and Leonardo DiCaprio do in Europe and the USA. Were Davina and Nadya made the subject and agents of ABC reporting, fairer and more representative images of a humane Indonesia would appear before Australian readers and viewers.

Ina Pane holding cat at “Animal Friends Jogja” by Animal People Forum is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

The second point is not about similarity, but difference. In understanding why standards of animal treatment in Indonesia often fall below those in Australia, it is helpful to understand how progressive causes of this kind catch on widely. They rely upon populations being drawn into shared conversations in which progressive positions are advocated and justified. This has not happened in Indonesia in the way it has here.

Indonesia has had to build its educational, economic and public health systems almost from scratch since it became independent in 1945, and has laboured to create for its population the prosperity taken for granted in Australia. Educational standards have not developed in accordance with the hopes of policy makers and citizens. Large segments of the Indonesian population lack access to basic information concerning health and sanitation, let alone emerging causes such as animal rights and environmental issues.

On the UNDP Human Development Index Australia is ranked sixth, while Indonesia is ranked 111th. Indonesian young people attend school for a mean of 8 years, while the mean for Australia is 12.7. These rankings reveal the difficulties the Indonesian government faces in empowering its population, and also explain the slower uptake of progressive causes.

Against this background, the ABC’s reliance upon Indonesia for images of cruelty is unfair to our northern neighbour. It is also unfair to Australians, for it compounds Australians’ ignorance of the history and contemporary conditions of life in the country. The coverage continues the unfairness post-colonial nations like Indonesia have had to encounter in building national systems from a position of massive disadvantage in comparison to prosperous settler nations like Australia. And it dissuades Australians from wanting to know more about Indonesia.

Changing the story

Is anyone to blame here? Not really. Animals Australia is doing what its mission requires it to do – draw cruelty to animals to the attention of Australians and to raise money to enable it to do this. The ABC knows the material will find approval from Australian viewers. Furthermore, it helps the ABC play a valuable public role in calling industries to account for their treatment of animals.

Yet this situation ought to be changed out of fairness to our Indonesian neighbours and for the benefit of young Australians needing a better knowledge of their region. Such changes will not be difficult: images of animal cruelty sourced from Indonesia should be reduced in ABC news coverage and replaced by images from other locations. This will not hurt the pro-animals cause at all.

And second, the ABC should establish a new relationship with an Indonesian partner, enabling Australians to learn that this humane cause is shared – not opposed – by our close neighbours. Animal cruelty is not an Indonesian specialisation, but is present everywhere, and Australians will benefit from gaining awareness of the similarities and differences to be encountered in the true story of animal welfare in Indonesia.

Julian Millie (Julian.Millie@Monash.edu) is Professor of Indonesian Studies in the Faculty of Arts at Monash University

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss