Prior to COVID-19, the Indonesian film industry was in the middle of an unprecedented boom, stimulating hundreds of millions of dollars in investment activity and consumer spending with no end in sight. Favourable government regulations were helping to accelerate growth, with theatre chains seeing big revenue increases and opening new locations almost every month. Indonesian consumers, for their part, proved eager to spend a share of their disposable income to watch the latest Marvel or Dilan film. All signs pointed to a very healthy pre-COVID movie scene, and industry players as well as public officials are eager to get it back.

In 2019 Avengers: Endgame grossed a record IDR 494.8 billion on 11.2 million tickets, figures that hint at the growing domestic appetite for film in Indonesia before COVID-19 threw the industry into chaos. Western films have long been popular, but this box office dominance by a Disney subsidiary is no mean feat given the country’s historical tendency toward protectionism. That tendency touched the film industry as recently as 2011, when Hollywood films were essentially banned for several months while a dispute raged over import licenses and tariffs.

Hollywood blockbusters are still the most reliable box office champions in Indonesia. But locally-produced content is catching up fast. In 2018, the highest grossing film in Indonesia was Avengers: Infinity War which according to industry analyst Bicara Box Office made IDR 351 billion on 8.1 million tickets. The second highest grossing film that year was Dilan 1990, which pulled in IDR 252.6 billion on 6.3 million viewers. Based on a popular novel and steeped in nostalgia for 1990s Bandung and jean jackets, Dilan 1990 was squarely pitched at domestic audiences—and it outperformed other Hollywood tent-poles released that year like Aquaman.

Pulling back a bit further reveals the full scale of the industry’s growth. In 2014, there were 16.2 million tickets sold for local films—by 2018, that figure had spiked to 52 million. The numbers for CGV—the second largest theatre chain in Indonesia—tell a similar story. Total admissions (for foreign and domestic films) went from 5.5 million in 2014 to 22.7 million in 2019. Revenue increased by more than four times, from IDR 332.6 billion in 2014 to IDR 1.4 trillion last year.

Much of this growth is being driven from the demand side—the total number of films screened by CGV in 2019 was actually less than in the previous year, and they have typically stuck to a mix of about 1/3 local content and 2/3 imported. The absolute supply and composition of films has not changed much in the last five years, suggesting that rapid growth in admissions is being driven mainly by Indonesians becoming more active consumers of films, hand in hand with increasing amounts of disposable income.

The government has also helped by getting out of the way. The state’s history with the film industry is long and contentious, often using cinema as a tool of propaganda to reinforce regime narratives, or restricting film imports during bouts of economic nationalism. At other times, cronies like Suharto confidant Sudwikatmono were allowed to maintain a monopoly on the distribution of imported films, concentrating profits in the hands of a select few.

In the 2000s, the theatrical exhibition market started inching toward competitiveness with the introduction of challengers like CGV, which in 2007 had a total of 3 theatres and 30 screens. Cinema21 (the chain originally founded by Sudwikatmono) is still the dominant movie theatre in the country, with a reported 1,012 out of 1,685 of total movie screens in 2018. However, they no longer enjoy exclusive rights on films, and have to compete on price and service with other chains.

In 2016 the government relaxed limits on foreign investment in local theatres and production companies. GIC, one of Singapore’s sovereign wealth funds, immediately invested IDR 3.5 trillion into Cinema21 which was used to finance expansion activities. CGV, whose majority shareholder is a Korean conglomerate run by a Samsung heir, also stepped up the pace of capital injections. After 2016 the pace of expansion really heated up. CGV went from 19 theatres and 139 screens in 2015 to 67 theatres and 389 screens in 2019, and were in the midst of constructing additional facilities when COVID-19 brought the industry to a standstill.

But there is one area that is still a bit of an open question – the quality of domestic production, and the ability of Indonesian cinema to have an impact outside of its own borders. The second highest-grossing domestic film of 2018 was Suzzanna: Bernapas Dalam Kubur, a ghost story based on real-life Indonesian scream queen Suzzanna (who is, incidentally, buried just a few feet from my wife’s grandmother and whose grave still attracts morbid looky-loos from time to time). This film was popular with Indonesian audiences, selling over 3.3 million tickets. But on the technical merits as a film, it is not particularly well-made. As Thomas Barker noted in a piece for The Conversation “Indonesia’s best films of the year are rarely the most popular.”

That may be starting to change. In 2017, arguably the best film of the year was also rewarded at the box office. Joko Anwar’s Pengabdi Setan, a remake of a 1980s classic about demonic possession, sold 4.2 million tickets taking it to the number one spot. Anwar is one of Indonesia’s most prolific and talented filmmakers, having directed classics like Kala and Pintu Terlarang. He can move fluently between genres and styles, and has focused on making films that amplify local myths and themes. Pengabdi Setan, for instance, is steeped in the imagery of the pocong, a ghost tied to Muslim burial practices in the region.

I spoke with Anwar earlier this year, and he told me that demand for quality films has been increasing lately, forcing the industry to produce better content. “Local audiences used to accept anything thrown at the cinema,” he said. “And many of these ineptly made movies landed on the box office list. Then nobody watched them anymore partly because people can access many movies from abroad easier with streaming platforms. Now filmmakers and film crews with skills are in demand. A few are film school graduates. But since there aren’t many film schools in Indonesia (less than 10), many learned from working.”

I was also curious if he had seen any improvement on the production side due to the government easing restrictions on foreign investment. Maybe with a more relaxed investment environment, it would be easier to structure financing deals or find distributors. But Anwar says that has not really been the case. “There haven’t been many movies financed by foreign investments,” he explained. “There are some, but only a few. It didn’t change the distribution scheme for Indonesian movies either.”

In fact, the overall quality of domestic production has picked up in recent years to the point where distributors are starting to come looking for content. Take the critically lauded Marlina the Murderer from director Mouly Surya, a beautiful meditation on rural life and gender roles that screened at Cannes in 2017. The short film Prenjak, directed by Wregas Bhanuteja, won an award at Cannes in 2016 and as Barker notes in The Conversation over the last 20 years Indonesian films have begun making more frequent appearances at international film festivals, gaining wider acclaim and winning awards.

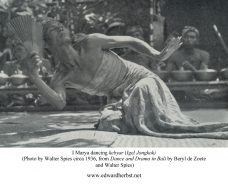

Nien Yuan Cheng reflects on the film screening and lecture, "Gender, Crossdressing and Androgyny in Balinese Dance", conducted by ethnomusicologist Edward Herbst under the aegis of the Bali 1928 repatriation project.

Documentation, Restoration, and Repatriation? Reflections on a dance film screening for the ‘Bali 1928’ project

This can be observed in Indonesia’s budding reputation as a hub for action, as well. The success of Gareth Evans’ The Raid in 2011 made Iko Uwais into an international action star, and Timo Tjahjanto’s neck-breaking flick The Night Comes For Us was released by Netflix in 2018 and has a 91% rating on Rotten Tomatoes. The horror streaming platform Shudder has also begun carrying more Indonesian films, all of which points to the improving quality of domestic productions.

Meanwhile, films like Dilan targeting local audiences will continue to nip at the heels of Hollywood blockbusters for top spot at the box office. With demand driving the construction of more theatres and higher quality films, with government regulations relaxed so capital can more easily flow to where it is needed, and with distributors eager for more local content, it seems like a matter of when, not if, the industry will snap back once theatres re-open and people are no longer afraid of the virus.

Given how favourable these structural conditions are, if it doesn’t bounce back quickly it will be a strong indication that consumer spending is going to be on a slow road to recovery as people conserve their wages and savings to spend on necessities, rather than diversions like movies—no matter how good they are. This intermission in the history of Indonesian cinema will one day end, and the industry is well-positioned to recover. The speed with which it does so will tell us a lot about how bad things got in the meantime.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss