Many Indonesian and non-Indonesian observers have lambasted Indonesia’s unscientific, slow and overly cautious approach to the COVID-19 outbreak. Many of these criticisms are on point. Precious time was lost when the Indonesian government stonewalled and ignored well-meaning international advice, failing to take aggressive actions to fix and address obvious shortcomings in the medical system. With sustained community transmission now occurring in many provinces, Indonesia has found itself in the same position as China at the beginning of this year.

Indonesia is undoubtedly resolved to bring this virus under control, though crisis communication and coordination of regional COVID-19 efforts by the central government have been lacking so far. The country’s efforts to mitigate the impact of the virus have been criticised for choppy policymaking and flip-flops, such as the issuing of conflicting regulations on motorcycle taxis by the Transportation and Health Ministries, causing confusion for passengers. In addition, the response often seems reactive rather than proactive, leading to frustrated regional governments who have been driven to act on their own accord.

In my opinion however, the reason for Indonesia’s tortured response is not ineffective governance so much as the country’s constrained menu of options to fight COVID-19. Limitations in place due to longer-term structural factors have been reflected in sub-optimal policy responses, which necessitate strategic caution and patience to consider second and third-order consequences.

COVID-19 is both a public health emergency and an economic crisis. As Indonesia can rely on neither strong socioeconomic buffers nor a robust healthcare system, Indonesian President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) has been forced to keep the economic and public health side of the ledger on an even keel. As the number of COVID-19 cases spiked in mid to late March, fears that the virus would spill-over to the rest of Indonesia stimulated strong public pressure for the government to impose a lockdown at the epicentre of the outbreak in the Greater Jakarta Region.

Considering Indonesia’s weak public health fundamentals, especially in regions outside of Java island, movement restrictions around the Greater Jakarta Region epicentre or a lockdown might have been prudent if implemented sufficiently early. After all, Indonesia faces serious shortages of medical equipment such as ventilators, protective equipment for medical staff, and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) testing facilities.

However, the economic costs were deemed too high. Rightly so—55% of Indonesians from street vendors to ojek drivers work in the informal sector and are reliant on daily wages—meaning that the orang kecil with the weakest financial buffers would bear the brunt of a lockdown policy. This is not theoretical—there has already been reports of people starving to death due to the loss of income. About 2 million Indonesian workers have already been furloughed or terminated. It would have been hard to organise enough economic and logistical support to sustain the population and keep businesses afloat if all economic activity was to cease.

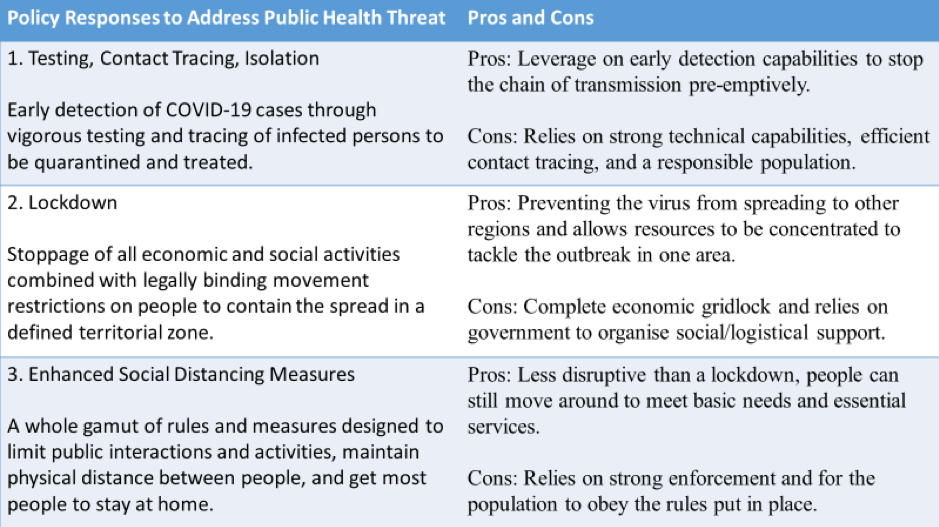

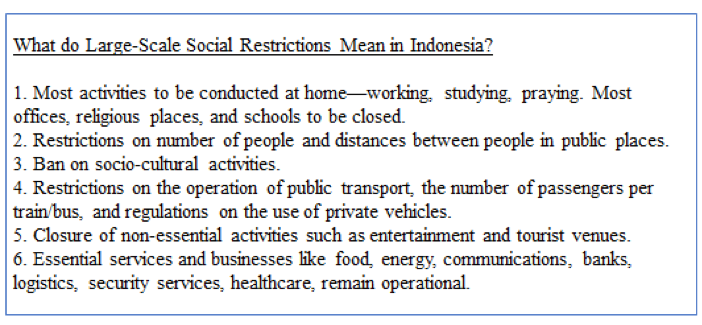

Therefore, roughly a month after the first COVID-19 cases were reported in early March, the central government finally settled on its policy tool of choice. On 31 March, the central government issued Government Regulation No. 21/2020 on Large-Scale Social Restrictions. This Government Regulation acts on statutory provisions under the 2018 Law on Health Quarantine. The restrictions are essentially enhanced social distancing measures that regional governments must obtain permission to implement, and which fall short of the systematic movement restrictions involved in a lockdown.

Compiled based on existing implementation of large-scale social restrictions by regional governments

Regional governments seeking to implement these social distancing measures must show proof of viral spread, demonstrate their ability to provide for the people’s welfare, and secure the approval of the Health Minister. Once approval has been obtained, regional governments can implement measures based on the guidelines to restrict activities in the workplace, schools, religious facilities and other public facilities.

In practice, the central government’s reliance on social distancing measures is a deeply imperfect solution to the issue of viral spread. The effectiveness of these measures is largely dependent on effective enforcement and the compliance of the population with the stipulated rules. Two weeks after the implementation of large-scale social restrictions in the Jakarta Capital Region, data from the Jakarta Department of Labour, Transmigration and Energy indicates that only one-quarter of employees in the capital city are working from home (1.013 million out of 4.84 million). Key central government officials have repeatedly harped on the importance of “personal discipline” in following these measures. Stricter enforcement by the police looks likely moving forward.

Imposing a coordinated response

The success of large-scale social restrictions is also heavily reliant on effective coordination between regional and central governments, as well as the individual capabilities of regional governments. This brings us to a second structural factor. Coordination is notoriously difficult and a long-standing problem both horizontally between regional governments, and vertically between different levels of government. Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, President Jokowi saw re-centralisation as key to addressing slow permit approvals needed for investment facilitation. This included centralising all permits and licensing requirements previously managed by various ministries, and passing a draft omnibus law on job creation to re-centralise regulatory authority in the central government.

The difficulty of coordination has to do with overlapping areas of authority that led to a central-regional government tussle in March, which has since been resolved in favour of the former. Indonesia’s decentralisation reforms were the product of a historical compromise between reformers who feared the excessive centralism of the Suharto era and those who feared that excessive regionalisation would lead to the disintegration of the Indonesian nation. The so-called “regional autonomy” produced a system halfway between a unitary state and a federalist state, with its contradictions painfully apparent in the recent outbreak.

This mixed system has produced a tortured jurisdictional struggle amid the novel multi-sectoral problem posed by COVID-19 and Indonesia’s reliance on regional governments to implement large-scale social restrictions. The amended 1945 Constitution stipulates that regional governments enjoy the widest possible autonomy, except when in relation to government affairs that by statute are stipulated as the affairs of the central government. Based on the 2018 Law on Health Quarantine, only the central government has the power to declare a regional quarantine or lockdown at the city, regency and provincial level. However, the 2014 Law on Regional Government stipulates that public health falls under the concurrent government umbrella that is the responsibility of the regional government. In short, regional governments with varying levels of healthcare capabilities initially lacked effective policy tools to combat an invisible virus spread by human contact.

Until late April, the imposition of large-scale social restrictions had been a double whammy for regional governments. Between 1-23 April, Indonesians from the virus epicentre were still allowed to travel around the country and regional governments could not legally prohibit their entry, so sparse resources had to be organised to screen, monitor, test and quarantine arrivals from high risk areas. Public health professionals feared that such travel could heighten and accelerate the viral transmission either during the annual mudik (exodus) when Indonesians return to their hometowns to celebrate the Idul Fitri holidays (22-27 May 2020), or when Indonesians can no longer find work in the cities.

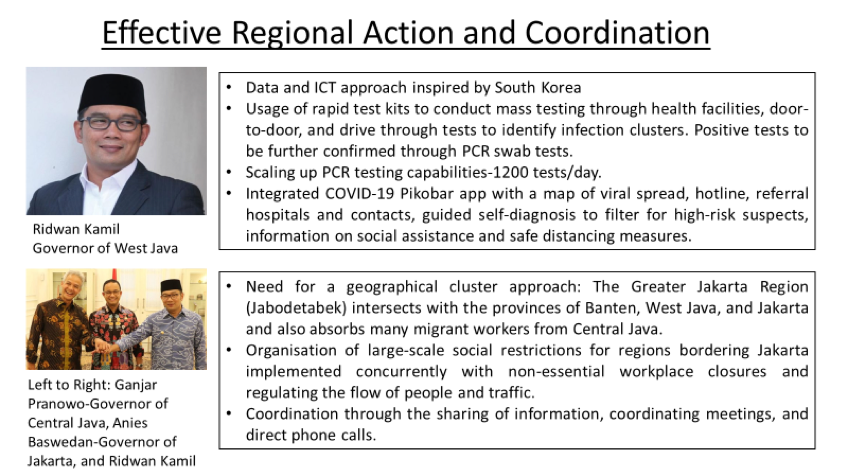

Reflecting frustrations with the central government’s over-cautious approach, regional governments had been most proactive in organising a policy response to the public health aspects of the coronavirus. In mid-March, Jakarta Governor Anies Baswedan became the first regional executive to organise large-scale closures of entertainment/tourist venues and work/school holidays as cases skyrocketed in Jakarta. By the end of March, mayors of other cities began putting in place road closures using concrete barriers (Tegal, Central Java) and setting up checkpoints to control the entry of goods and people (Surabaya, East Java). With extremely limited medical capabilities on Papua island, the Mayor of Sorong in West Papua defiantly declared that he was prepared to go to jail as he announced an airport closure on 1 April. A YouTube video dated 4 April showed that the airport was closed, even though the central government insisted that only it could authorise an airport closure.

Amid the variety of policy innovations taken by regional governments, the central government had to restrain regional governments, concerned that policies taken must give due regard to organising social assistance and avoiding disruption and panic. Government Regulation No. 21/2020 on Large-Scale Social Restrictions provided the key legal framework to maintain central government oversight over the policies of the regional governments, with governors playing a key coordinating role. The regulation also provided policy space for regional governments to implement social distancing measures. It has also clarified the chain of command. Plans to implement a “local lockdown” in the cities of Tegal and Tasikmalaya were scrapped and these cities instead sought approval from the Health Minister to introduce large-scale social restrictions.

Additionally, regional governments have begun to coordinate their large-scale social restrictions based on geographical clusters. This has already come into force in the Greater Jakarta Region and the Greater Bandung Region, while Surabaya city has begun to make plans with its neighbouring regencies to do the same with the support of East Java Governor Khofifah. Despite early concerns that regional governments would not be able to work together, it appears that regional leaders in Java have risen to the occasion. Large-scale social restrictions require high levels of regional coordination and effective enforcement. The relatively effective ad-hoc inter-regional cooperation so far has underscored the strength of the system of direct local elections that has improved vertical accountability and elected a new breed of effective reformist leaders skilled in public relations management to regional executive positions.

From social restrictions to travel restrictions

The key takeaway is that Indonesia’s policy response to COVID-19 has been constrained by a policy triangle between public health, socioeconomic considerations, and central-regional administrative strain, resulting in a very difficult balancing act. The central government’s recent decision to prohibit the annual mudik (exodus) from the Greater Jakarta Region will temporarily stop all forms of road, train, sea, and air transportation that can facilitate the entry or exit of people, with exemptions for security personnel and logistics. This regulation is applicable between 24 April and 31 May.

Without social safety nets, Indonesia risks political instability over COVID-19

Economic disasters have a history of bringing down governments in Indonesia; COVID-19 impacts hardest on the disadvantaged in an already fragile system.

The big question is whether enough socioeconomic assistance can be organised quickly enough to cushion the economic pain. I am optimistic it can be if the current patchwork of central government assistance programmes can be synchronised with concurrent efforts by regional governments to offer aid to the poor and vulnerable.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss