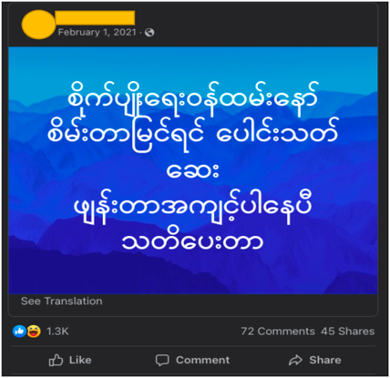

On 1 February 2021, the day Myanmar’s military launched an early morning raid to arrest key politicians and seize political power, a seemingly innocuous post appeared on a Facebook group devoted to Myanmar agriculture. Memifed with bright blue colours and large font, the text read: “I’m agricultural staff. So, I have a habit of using herbicide when I see green. Be warned.”

By combining a reference to the Myanmar military—the green colour of soldiers’ uniforms and the army’s political party—with a typical farming activity—the use of herbicide to kill weeds—the slogan yoked a common cultural reference to everyday agrarian work for a revolutionary end. The post came from “agricultural staff,” a reference to government employees within the Ministry of Agriculture, and anticipated the Civil Disobedience Movement that would take off in the coming days with widespread strikes against the junta’s takeover. Published in a public group with over 118,000 members, the post showcased the rural character of online defiance.

In a new open access article in Big Data & Society, we analyse this and other examples of what we call organic online politics: forms of digital mobilisation that grow from specific conditions, material concerns, and repertoires of resistance in the countryside. We demonstrate how, after Myanmar’s military coup, Facebook users in farming groups harnessed the platform’s affordances to respond to democratic crisis in ways rooted in agrarian histories. More broadly, this concept brings into focus the ways in which rural dynamics shape data practices.

Focusing on the role of rural places in digital mobilisation is vital, not only because two thirds of the population of the world’s low-income countries is rural, but also because of the central role that rural people have historically played in global revolutions. Analysing the agrarian dynamics of online dissent enables us to root data politics in longer patterns of rural resistance, and to see how distinctive forms of rural mobilisation are woven into broader political struggles.

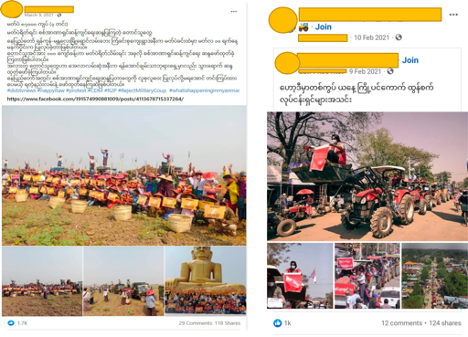

In the case of Myanmar, farmers’ Facebook groups shaped the trajectory of anti-authoritarian mobilisation through farmer protests and tractor protests, coupled with strategic actions to renege on agricultural bank loans. Farmers’ groups were also some of the first dissidents to call attention to food security and supply chain issues—critical dynamics that would come to shape the possibilities for protest in the months to come.

Southeast Asia has become a hotbed of both digital activism and digital disinformation and surveillance in recent years, a trend that accompanies resurgent authoritarianism and leads to new questions about data justice. But, with notable exceptions, limited work has considered the role digital connection plays in the region’s rural politics.

Social media dissidence has likely facilitated a civil disobedience movement with greater grassroots support than ever—a development that the Tatmadaw might find difficult to halt.

Digital contention in post-coup Myanmar

Our own inquiry emerged from our research team’s previous experience, including watching smartphones arrive to Myanmar’s countryside and monitoring the hate speech on Myanmar Facebook. In late 2020, we began digital ethnography and then large-scale monitoring of over 200 Burmese language Facebook pages and groups related to agriculture. We used Crowdtangle, a public content monitoring tool owned by Meta [see funding disclosure below], to collect top posts each week, and then coded them thematically and discussed them as a team. Eventually, we amassed an original archive of over 2,000 popular posts.

Our original aim was to understand how farmers and traders were using social media. Facebook moved quickly to secure customers after Myanmar privatised telecommunications in 2014, becoming Myanmar’s dominant platform and one of the primary ways that Myanmar people experienced the internet. Facebook groups and pages related to agriculture proliferated. For the estimated two thirds of Myanmar’s population who live in rural areas and rely, at least in part, on farming, these provided vital sources of agrarian commerce and knowledge.

All this changed after the coup. As we continued to collect and analyse data from farming groups, we observed a massive drop off in overall internet traffic, a downshift that corresponded to the military junta’s internet shutdowns, restrictions against using Facebook, and targeted censorship. But we also found changes in the content of these groups. Consistent with broader trends across Myanmar Facebook, in the days and weeks that followed the coup, farming groups erupted with political news and calls to support the Civil Disobedience Movement. After peaceful protests were met with brutal crackdowns, images of and information about protecting oneself from violence increased.

The figure below displays the immediate shift towards political content after the coup, highlighting spikes on key protest dates. But it also shows the eventual return to more banal practices of selling seeds and exchanging agricultural advice, as fear and self-censorship took hold.

A striking finding from our research is that patterns of online dissent in farming Facebook groups were distinct from those in urban areas. Online politics are shaped not only by authoritarian repression and national political trajectories, but also by rural communities and their histories. In the days after the coup, groups filled with concerns over food prices and rice market collapse. Practical worries were interwoven with existential crises. One post declared: “Due to the coup, the whole country is in turmoil. It’s not just the price of rice; there will be damage to everything.” Another mourned, and called for action: “We fear not only for the rice market but also for the future of our generation. So, now the youth are on the road to strike.”

Posts pointed out that suffering was nothing new for farmers. In one image that circulated across multiple agriculture groups, an old man stands with a raised fist in a protest line of men, similarly clad in the familiar rural attire of baseball hats, flip flops, and traditional longyis. In his other hand, he holds a cardboard sign that says: “We farmers don’t want to go back to the era of the rice tax.” This poignant reference to the poverty and hardships farmers endured under a previous regime exemplifies the ways in which online dissent was grounded in rural histories.

By documenting resistance, such as the farmers’ and tractor protests shown above, and calling for particular forms of dissent, such as posts urging farmers not to repay loans from the government agricultural bank, Myanmar farmers’ Facebook groups powerfully shaped anti-authoritarian mobilisation. Their demands pinpointed specific needs—from agricultural inputs to export markets—while bringing critical attention to farmers’ pivotal role in maintaining the land, feeding the country, and financing the state.

Since we collected our data in early 2021, much has changed. While Facebook provided fertile ground for public dissent in the initial months of the Myanmar Spring Revolution, internet restrictions and surveillance, as well as skyrocketing data costs and targeted arrests of social media influencers, have meant that online activity has been suppressed. Users have splintered across Twitter, Tiktok, and encrypted apps like Signal and Telegram. Digital mobilisation has not stopped, but rather adapted from public dissent to click-to-donate campaigns, video games, and YouTube videos of revolutionary songs posted by accounts that promise to use advertising revenue to fund anti-military forces and displaced people.

These innovative ways of circumventing online repression present new methodological challenges, even as they evidence the creativity of the resistance. Doing this research together was difficult, invigorating, and, at times, heartbreaking. Our analysis shows how digital mobilisation is grounded in agrarian resistance and renewal, and endows us with deep respect for Myanmar people at home and abroad who continue to employ digital tools in the ongoing struggle for freedom.

Disclosure: Data collection and analysis were funded by a grant from Facebook Research on digital literacy, demographics and misinformation. Facebook had no oversight or control over the research process and has not reviewed the analysis or findings.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss